In 1999 this correspondent had front row seats to the first internet bubble, as a private client portfolio manager at Merrill Lynch in London. Clients were scrambling over each other to buy technology stocks. ‘Giddy’ doesn’t really do the mania justice. ‘Insane’ comes closer to describing the popular mood.

James Glassman and Kevin Hassett had just published a book, Dow 36,000, the title of which speaks for itself. Merrill’s private client management in London had issued a copy to all staff. Could have been worse. They could have made us drink Kool-Aid spiked with cyanide.

AOL was on the cusp of merging with Time Warner in what would become one of the most value-destructive mergers in corporate history.

Boo.com was in the process of burning through $190 million in vain hopes of establishing an online clothing business.

Lastminute.com, an online travel agency, was just about to squeeze through the IPO window in the UK, before that window slammed violently shut behind it.

Pets.com was still selling dogfood on the internet.

As someone with a keen interest in the emerging economy of the worldwide web, we had stumbled on a website called f**kedcompany.com. The basis of the website was to act as a dotcom deadpool – you could nominate ridiculous businesses busily burning through their seed capital, and the more outrageously destructive their flameout, and the more human misery involved as those businesses crashed back to earth, the more points you scored. Over time it developed a second life as a chatroom for VC (Venture Capital) investors, regular investors, or their asset managers, and sundry rubberneckers to spread rumour, innuendo and gossip about dotcom businesses and their mayfly shelf-lives.

We still remember the post from somebody calling himself ‘Stanford MBA’.

It was brief and to the point:

“We have stumbled upon the perfect business model. We will lose money on every sale, and we will make up for up it in volume.”

To this day we can’t be entirely sure whether ‘Stanford MBA’ was joking or not. Given the sort of businesses that did get funding at the time, he might have been deadly serious.

So with the benefit of hindsight, all the warning signs were there.

The warning that had the most immediacy came direct from the US stock market. The market capitalisation of the online discount brokerage Charles Schwab had just overtaken that of our then employer, the full service investment house Merrill Lynch – which had, Stateside, an army of 13,000 human brokers. It was clear that something very significant was going on, and not necessarily happening to our advantage.

So we quit.

We could sense that something transformative was in the air.

The internet was clearly changing everything it touched: the music business had been the first to get “disintermediated” and see its profit margins melt like a snowflake in the Sahara. The news business was next. It didn’t look like finance was going to emerge unscathed.

We had just read a book called The Cluetrain Manifesto. Ironically enough, we had seen it referenced in a research note by Merrill Lynch’s own technology analyst, Henry Blodget. (Blodget would later be found guilty of violations of securities laws and barred from the securities industry for life.)

The Cluetrain Manifesto essentially spoke to the end of business as usual, thanks to the transformative power of the internet. It was a modern day reworking of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses – the publication of which is widely seen as having ignited the Reformation of the Catholic Church. You can see the original website here.

It was a heady time. We were already disillusioned with office politics, and with the ever-growing bureaucracy and footling regulation of the financial services industry. We were ready for a change of scene.

It struck us that anyone who had a website also had their very own TV station. (Provided they wanted to upload video to it, that is.)

Back then, pretty much anybody who enjoyed internet access had to get it via dial-up modems. As you can probably remember, download speeds for most users were S-L-O-W.

Anyone who had a website also had their very own radio station too. (Technically, on-demand audio – but what’s the difference ? In its favour, audio streamed online didn’t require shelling out for a radio licence.) Audio streamed online was far less bandwidth intensive. Plus, to put out professional-sounding audio content required a fraction of the cost of high quality video material.

So we set up a company – Moonrock New Media – hired a professional sound engineer, and recorded a 15 minute demo in order to attract investors. The demo webcast of Moonrock Radio was recorded on April 1st, 2000 – just as the dotcom bubble was beginning to implode on itself.

In Moonrock Radio, what we wanted to create was essentially CNBC in radio form, minus the conflicted nonsense.

The ‘vision’ was to mix financial news with commentary, music, stock picks, and a dash of caustic humour.

The name ‘Moonrock’ was a conflation of Money and Rock. It was really, in intent, the bastard child of CNBC and MTV.

And it flopped. But not before our demo, recorded on April Fools’ Day 2000, had enabled us to raise a six-figure sum from clients, friends and family – enough to finance the project for at least a full year. And although we never found an audience that we were able to monetize, we don’t regret one second of the time we spent on the experiment. (Happily, we remain on speaking terms with those angel investors. We all knew we were taking a risk.)

Whereas most in the City watched safely from the sidelines, this correspondent got well and truly stuck in to Dotcom Bubble 1.0, and has the scars to prove it. The experience left all involved with a profound respect for all forms of entrepreneurship.

And while Moonrock Radio never managed to find a commercial audience, we like to think that anyone who listened to that original webcast would probably have benefited from it.

We listed five stocks, for example, as part of our ‘Not’ list back in April 2000. Although we didn’t state it explicitly, the intention was that anyone who shared our scepticism about those businesses’ market valuations could do worse than consider shorting them.

The fate of the ‘Nots’

Amazon.com (AMZN US): Two years later (as at end March 2002), the stock was down by 79%.

Freeserve plc (FRE LN) was taken over by France Telecom in 2000 for roughly the same valuation as its IPO in July 1999.

Softbank (9984 JP): Two years later, the stock was down by 92%.

Lastminute.com (LMC LN): Two years later, the stock was down by 75%.

Marks and Spencer (MKS LN): Two years later, the stock was up by 64% (you don’t win ‘em all).

Average performance of the ‘Nots’: -45%.

We also listed five stocks as part of our ‘Hot’ list – the clear implication being that these were great businesses, but by dint of not being dotcoms, in early 2000 their real value was being ignored by a highly inefficient market obsessed with all things internet.

The fate of the ‘Hots’

ST Micro (STM FP): Two years later, the stock was down by 40%.

Unilever (ULVR LN / UL US): Two years later, the stock was up by 48%.

Kemet (KEM US): Two years later, the stock was down by 39%. (Again, you don’t win ‘em all.)

Diageo (DGE LN): Two years later, the stock was up by 108%.

Washington Mutual (WM US): Two years later, the stock was up by 100%.

Average performance of the ‘Hots’: +35%.

(First lesson from the above ? No matter how much conviction you have in a great stock, or a lousy one, for that matter, you have to diversify.)

The sell-off that afflicted the G7 stock markets from 2000 was widely seen as a disaster for so-called TMT (Technology; Media; Telecoms). Whatever sector they were in, though, the share prices of the most egregiously popular companies simply became unsustainably high – and most of those companies happened to be pure-play dotcoms without any real likelihood of achieving consistent profitability, let alone market dominance.

At the same time, plenty of stocks that in early 2000 were perceived as boring “old economy” irrelevances turned out to be fantastically profitable over the months to come. All in all, looking back at what was effectively an equity long/short portfolio, Moonrock’s picks did ok. Shame the business itself didn’t work out.

(Second lesson of the above, for putative VC investors: back people with plenty of experience in their specific field. In early 2000 this correspondent knew a little about the stock market, but next to nothing about the media business – especially one that would be delivering its product exclusively online.)

The fire next time

“God gave Noah the rainbow sign /

No more water, the fire next time.”

- From The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin.

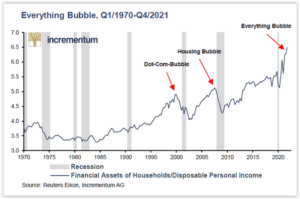

The reason why the market environment is now so much scarier than early 2000 from the vantage point of June 2022 is simple. Whereas the millennial bubble was in dotcom stocks and almost nothing else, Bubble 2.0 is in just about everything. It is universal. It goes beyond a segment of the stock market (technology) to take in virtually all of the US stock market, and those of most other developed economies, too.

Worse still, it transcends the asset class of listed equities and has managed to infect global debt markets, and many property markets, as well.

We now face the problem of an “Everything Bubble”.

In their authoritative research piece ‘In Gold We Trust’, the good folk at Incrementum AG point out that

“We have referred to the so-called “everything bubble” on several occasions. Now it looks as if this asset price inflation will be slowed down or reversed and financial capital will increasingly be shifted into real assets.”

The explicit overvaluation of bonds – admittedly, one in the process of slowly correcting – is now much worse than that of stocks, in that investment grade bonds now offer no margin of safety whatsoever – they are almost guaranteed to lose their value in real terms for anybody choosing to buy them today. The danger is compounded by the regulatory imperative that pension funds and advised private investors hold government bonds because they are deemed “riskless”. That is a sick joke.

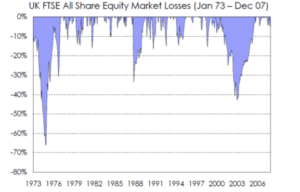

A case in point: the stagflationary 1970s. Courtesy of the Arab oil shocks, the mid-1970s was a disaster for all traditional forms of investment. The following charts relate to the UK market but most western markets would suffer a similar fate over the same period. (Data courtesy of Frontier Capital Management LLP.)

First, the stock market.

In nominal terms, the mid-70s was a dreadful time to own UK stocks.

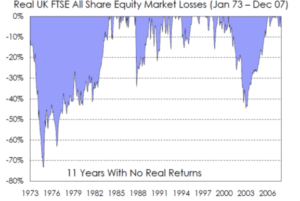

But in real (after-inflation) terms, it was far worse:

An investor who bought UK stocks in 1973 had to wait for 11 years just to break even, after the impact of high inflation.

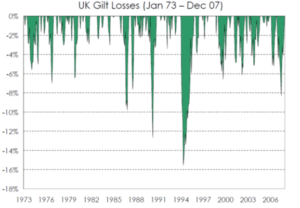

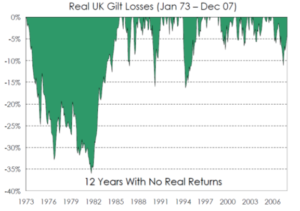

Then there was the bond market.

Those downward spikes for bondholders throughout the 1970s look bad enough – until you factor in the real returns, adjusting again for inflation:

For bondholders, the 1970s was an unmitigated disaster. The hapless UK government bond investor in 1973 had to wait until 1985 just to get his money back. An environment of stagnant growth combined with high inflation – which we may yet experience for ourselves – is toxic.

But the situation for bond investors is much more dangerous, given ubiquitous overvaluation, today.

So if bonds are uninvestible today, what about (US) stocks ?

Our favourite metric for assessing the US stock market, referred to here passim, is Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted p/e ratio (or CAPE) for the S&P 500 stock index. This takes the 10 year historic average of prior earnings in order simply to smooth out the shorter term price volatility.

US market CAPE ratio – 1880 to 2022

(Source: http://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe/)

The US stock market currently trades on a Shiller p/e of over 32. Its long run average is 17. Assuming that markets mean revert over time, that suggests that the US market is roughly 80% overvalued relative to its long run average.

While we acknowledge that the economics of the internet mean that some small number of companies can enjoy “winner take all” benefits (Amazon and Google being prime examples), by definition not every company can. And in the meantime, the internet also facilitates the continuous introduction of robust competition in, well, internet time. At the margin, permanent global competition ought to drive corporate profit margins down – and if the market doesn’t ultimately do it, anti-trust law assisted by populist politicians will.

For investors today, looking for reasons why the market has remained so abnormally expensive for such an extended period of time may be something of a fool’s errand. In all market matters, the truth is rarely pure and never simple. But the price is the price, and if we don’t respect it, we are likely to be poorly served by casually overpaying to own stuff.

In our book, Investing through the Looking Glass, we examine the causes of how we collectively got into this mess. The guilty players all get their own chapter headings, namely:

- The banks

- The central banks

- Economists and financial theorists

- Fund managers.

But rather than offer its readers nothing more than a glass of whisky and a loaded revolver, we also offer solutions to our current predicament. Those respective chapter headings are:

- Value investing

- Trend-following

- Gold.

Value investing in listed stocks is clearly a primary focus of our business – on a global and unconstrained basis – unconstrained by geography and business sector, and focussing entirely on bottom up, defensible value. In our discretionary wealth management business, we also invest in trend-following funds, and in precious metals, and in cheap, cash-generative, precious metals miners.

Our point being there is no single magic bullet out there. If you don’t know what’s ahead but you fear for the worst (which we do), it makes sense to diversify as widely as possible.

What is different this time is the general mood. In 2000, the air was electric with the hopes and dreams of a new era, as ridiculous as they now seem with hindsight. But here in 2022, we are living through what is surely the tail end of one of the most reviled bull markets in history. Nothing feels quite real – which is what happens when you allow a bunch of unelected bureaucrats at the world’s central banks to play unlimited games with the monetary system.

The single most important characteristic of any investment you make is its starting valuation when you buy it. Nothing else comes close.

The valuations of most stock markets are close to, or at, record highs.

The valuations of most bond markets are close to, or at, record highs.

Central bankers like to believe that it’s impossible to identify bubbles before they burst. With all the respect due to them – i.e. none whatsoever – that is nonsense. It was evident to us and many others in early 2000 that the market had got ahead of itself. Moonrock Radio simply had the good fortune – from the perspective of its handful of listeners, at any rate – to launch within a few weeks of, but also explicitly identify, the top.

That demo webcast also highlighted the fate of Julian Robertson, the founder of the Tiger Management hedge fund, which is instructive. Robertson had a long and successful career in fund management, but it ended under the cloud of early 2000. Robertson was forced to capitulate on the old economy value stocks he owned – and he sold out at the worst time in history, just as those same stocks were on the verge of bouncing back. But he was also too early in shorting dotcom stocks. He missed the top of the market by just a matter of weeks. If he had been later to the game, he might have made out like a bandit from Nasdaq’s collapse after March 2000. As it is, he was whipsawed on both sides. He sold out his value stocks too soon, and he was also too soon in shorting the TMT sector. Moral of the tale ? Never use leverage if you can avoid it. And never make your solvency dependent on your ability to time the market, because for 99.999% of investors, market timing is impossible.

We humbly submit this may soon be one of the best times in history to be a value investor – whether in relative, or absolute terms. We may be wrong – QE and ZIRP have been with us for over 10 whole years now – but we sense a disturbance in the force, as the Fed continues to hike, and bond yields and stocks creak and fragment under the accumulated pressure of an at least decade-long foray into absurdity.

In the days of ancient Rome, it is said that during a triumphal procession, a military commander would be accompanied by an Auriga – a slave who would stand behind him, whispering in his ear Memento homo: remember, you too are mortal.

Someday, perhaps quite soon, this bull market in everything is going to end – if that process hasn’t indeed already begun. Now is probably a good time to be highly discerning – to be concentrating on stocks possessing what Benjamin Graham would have called a “margin of safety”. If many of those stocks are to be found outside the US market pressure cooker, so be it.

Last word this week should probably go, then, to Warren Buffett:

“Cash combined with courage in a crisis is priceless.”

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

In 1999 this correspondent had front row seats to the first internet bubble, as a private client portfolio manager at Merrill Lynch in London. Clients were scrambling over each other to buy technology stocks. ‘Giddy’ doesn’t really do the mania justice. ‘Insane’ comes closer to describing the popular mood.

James Glassman and Kevin Hassett had just published a book, Dow 36,000, the title of which speaks for itself. Merrill’s private client management in London had issued a copy to all staff. Could have been worse. They could have made us drink Kool-Aid spiked with cyanide.

AOL was on the cusp of merging with Time Warner in what would become one of the most value-destructive mergers in corporate history.

Boo.com was in the process of burning through $190 million in vain hopes of establishing an online clothing business.

Lastminute.com, an online travel agency, was just about to squeeze through the IPO window in the UK, before that window slammed violently shut behind it.

Pets.com was still selling dogfood on the internet.

As someone with a keen interest in the emerging economy of the worldwide web, we had stumbled on a website called f**kedcompany.com. The basis of the website was to act as a dotcom deadpool – you could nominate ridiculous businesses busily burning through their seed capital, and the more outrageously destructive their flameout, and the more human misery involved as those businesses crashed back to earth, the more points you scored. Over time it developed a second life as a chatroom for VC (Venture Capital) investors, regular investors, or their asset managers, and sundry rubberneckers to spread rumour, innuendo and gossip about dotcom businesses and their mayfly shelf-lives.

We still remember the post from somebody calling himself ‘Stanford MBA’.

It was brief and to the point:

“We have stumbled upon the perfect business model. We will lose money on every sale, and we will make up for up it in volume.”

To this day we can’t be entirely sure whether ‘Stanford MBA’ was joking or not. Given the sort of businesses that did get funding at the time, he might have been deadly serious.

So with the benefit of hindsight, all the warning signs were there.

The warning that had the most immediacy came direct from the US stock market. The market capitalisation of the online discount brokerage Charles Schwab had just overtaken that of our then employer, the full service investment house Merrill Lynch – which had, Stateside, an army of 13,000 human brokers. It was clear that something very significant was going on, and not necessarily happening to our advantage.

So we quit.

We could sense that something transformative was in the air.

The internet was clearly changing everything it touched: the music business had been the first to get “disintermediated” and see its profit margins melt like a snowflake in the Sahara. The news business was next. It didn’t look like finance was going to emerge unscathed.

We had just read a book called The Cluetrain Manifesto. Ironically enough, we had seen it referenced in a research note by Merrill Lynch’s own technology analyst, Henry Blodget. (Blodget would later be found guilty of violations of securities laws and barred from the securities industry for life.)

The Cluetrain Manifesto essentially spoke to the end of business as usual, thanks to the transformative power of the internet. It was a modern day reworking of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses – the publication of which is widely seen as having ignited the Reformation of the Catholic Church. You can see the original website here.

It was a heady time. We were already disillusioned with office politics, and with the ever-growing bureaucracy and footling regulation of the financial services industry. We were ready for a change of scene.

It struck us that anyone who had a website also had their very own TV station. (Provided they wanted to upload video to it, that is.)

Back then, pretty much anybody who enjoyed internet access had to get it via dial-up modems. As you can probably remember, download speeds for most users were S-L-O-W.

Anyone who had a website also had their very own radio station too. (Technically, on-demand audio – but what’s the difference ? In its favour, audio streamed online didn’t require shelling out for a radio licence.) Audio streamed online was far less bandwidth intensive. Plus, to put out professional-sounding audio content required a fraction of the cost of high quality video material.

So we set up a company – Moonrock New Media – hired a professional sound engineer, and recorded a 15 minute demo in order to attract investors. The demo webcast of Moonrock Radio was recorded on April 1st, 2000 – just as the dotcom bubble was beginning to implode on itself.

In Moonrock Radio, what we wanted to create was essentially CNBC in radio form, minus the conflicted nonsense.

The ‘vision’ was to mix financial news with commentary, music, stock picks, and a dash of caustic humour.

The name ‘Moonrock’ was a conflation of Money and Rock. It was really, in intent, the bastard child of CNBC and MTV.

And it flopped. But not before our demo, recorded on April Fools’ Day 2000, had enabled us to raise a six-figure sum from clients, friends and family – enough to finance the project for at least a full year. And although we never found an audience that we were able to monetize, we don’t regret one second of the time we spent on the experiment. (Happily, we remain on speaking terms with those angel investors. We all knew we were taking a risk.)

Whereas most in the City watched safely from the sidelines, this correspondent got well and truly stuck in to Dotcom Bubble 1.0, and has the scars to prove it. The experience left all involved with a profound respect for all forms of entrepreneurship.

And while Moonrock Radio never managed to find a commercial audience, we like to think that anyone who listened to that original webcast would probably have benefited from it.

We listed five stocks, for example, as part of our ‘Not’ list back in April 2000. Although we didn’t state it explicitly, the intention was that anyone who shared our scepticism about those businesses’ market valuations could do worse than consider shorting them.

The fate of the ‘Nots’

Amazon.com (AMZN US): Two years later (as at end March 2002), the stock was down by 79%.

Freeserve plc (FRE LN) was taken over by France Telecom in 2000 for roughly the same valuation as its IPO in July 1999.

Softbank (9984 JP): Two years later, the stock was down by 92%.

Lastminute.com (LMC LN): Two years later, the stock was down by 75%.

Marks and Spencer (MKS LN): Two years later, the stock was up by 64% (you don’t win ‘em all).

Average performance of the ‘Nots’: -45%.

We also listed five stocks as part of our ‘Hot’ list – the clear implication being that these were great businesses, but by dint of not being dotcoms, in early 2000 their real value was being ignored by a highly inefficient market obsessed with all things internet.

The fate of the ‘Hots’

ST Micro (STM FP): Two years later, the stock was down by 40%.

Unilever (ULVR LN / UL US): Two years later, the stock was up by 48%.

Kemet (KEM US): Two years later, the stock was down by 39%. (Again, you don’t win ‘em all.)

Diageo (DGE LN): Two years later, the stock was up by 108%.

Washington Mutual (WM US): Two years later, the stock was up by 100%.

Average performance of the ‘Hots’: +35%.

(First lesson from the above ? No matter how much conviction you have in a great stock, or a lousy one, for that matter, you have to diversify.)

The sell-off that afflicted the G7 stock markets from 2000 was widely seen as a disaster for so-called TMT (Technology; Media; Telecoms). Whatever sector they were in, though, the share prices of the most egregiously popular companies simply became unsustainably high – and most of those companies happened to be pure-play dotcoms without any real likelihood of achieving consistent profitability, let alone market dominance.

At the same time, plenty of stocks that in early 2000 were perceived as boring “old economy” irrelevances turned out to be fantastically profitable over the months to come. All in all, looking back at what was effectively an equity long/short portfolio, Moonrock’s picks did ok. Shame the business itself didn’t work out.

(Second lesson of the above, for putative VC investors: back people with plenty of experience in their specific field. In early 2000 this correspondent knew a little about the stock market, but next to nothing about the media business – especially one that would be delivering its product exclusively online.)

The fire next time

“God gave Noah the rainbow sign /

No more water, the fire next time.”

The reason why the market environment is now so much scarier than early 2000 from the vantage point of June 2022 is simple. Whereas the millennial bubble was in dotcom stocks and almost nothing else, Bubble 2.0 is in just about everything. It is universal. It goes beyond a segment of the stock market (technology) to take in virtually all of the US stock market, and those of most other developed economies, too.

Worse still, it transcends the asset class of listed equities and has managed to infect global debt markets, and many property markets, as well.

We now face the problem of an “Everything Bubble”.

In their authoritative research piece ‘In Gold We Trust’, the good folk at Incrementum AG point out that

“We have referred to the so-called “everything bubble” on several occasions. Now it looks as if this asset price inflation will be slowed down or reversed and financial capital will increasingly be shifted into real assets.”

The explicit overvaluation of bonds – admittedly, one in the process of slowly correcting – is now much worse than that of stocks, in that investment grade bonds now offer no margin of safety whatsoever – they are almost guaranteed to lose their value in real terms for anybody choosing to buy them today. The danger is compounded by the regulatory imperative that pension funds and advised private investors hold government bonds because they are deemed “riskless”. That is a sick joke.

A case in point: the stagflationary 1970s. Courtesy of the Arab oil shocks, the mid-1970s was a disaster for all traditional forms of investment. The following charts relate to the UK market but most western markets would suffer a similar fate over the same period. (Data courtesy of Frontier Capital Management LLP.)

First, the stock market.

In nominal terms, the mid-70s was a dreadful time to own UK stocks.

But in real (after-inflation) terms, it was far worse:

An investor who bought UK stocks in 1973 had to wait for 11 years just to break even, after the impact of high inflation.

Then there was the bond market.

Those downward spikes for bondholders throughout the 1970s look bad enough – until you factor in the real returns, adjusting again for inflation:

For bondholders, the 1970s was an unmitigated disaster. The hapless UK government bond investor in 1973 had to wait until 1985 just to get his money back. An environment of stagnant growth combined with high inflation – which we may yet experience for ourselves – is toxic.

But the situation for bond investors is much more dangerous, given ubiquitous overvaluation, today.

So if bonds are uninvestible today, what about (US) stocks ?

Our favourite metric for assessing the US stock market, referred to here passim, is Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted p/e ratio (or CAPE) for the S&P 500 stock index. This takes the 10 year historic average of prior earnings in order simply to smooth out the shorter term price volatility.

US market CAPE ratio – 1880 to 2022

(Source: http://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe/)

The US stock market currently trades on a Shiller p/e of over 32. Its long run average is 17. Assuming that markets mean revert over time, that suggests that the US market is roughly 80% overvalued relative to its long run average.

While we acknowledge that the economics of the internet mean that some small number of companies can enjoy “winner take all” benefits (Amazon and Google being prime examples), by definition not every company can. And in the meantime, the internet also facilitates the continuous introduction of robust competition in, well, internet time. At the margin, permanent global competition ought to drive corporate profit margins down – and if the market doesn’t ultimately do it, anti-trust law assisted by populist politicians will.

For investors today, looking for reasons why the market has remained so abnormally expensive for such an extended period of time may be something of a fool’s errand. In all market matters, the truth is rarely pure and never simple. But the price is the price, and if we don’t respect it, we are likely to be poorly served by casually overpaying to own stuff.

In our book, Investing through the Looking Glass, we examine the causes of how we collectively got into this mess. The guilty players all get their own chapter headings, namely:

But rather than offer its readers nothing more than a glass of whisky and a loaded revolver, we also offer solutions to our current predicament. Those respective chapter headings are:

Value investing in listed stocks is clearly a primary focus of our business – on a global and unconstrained basis – unconstrained by geography and business sector, and focussing entirely on bottom up, defensible value. In our discretionary wealth management business, we also invest in trend-following funds, and in precious metals, and in cheap, cash-generative, precious metals miners.

Our point being there is no single magic bullet out there. If you don’t know what’s ahead but you fear for the worst (which we do), it makes sense to diversify as widely as possible.

What is different this time is the general mood. In 2000, the air was electric with the hopes and dreams of a new era, as ridiculous as they now seem with hindsight. But here in 2022, we are living through what is surely the tail end of one of the most reviled bull markets in history. Nothing feels quite real – which is what happens when you allow a bunch of unelected bureaucrats at the world’s central banks to play unlimited games with the monetary system.

The single most important characteristic of any investment you make is its starting valuation when you buy it. Nothing else comes close.

The valuations of most stock markets are close to, or at, record highs.

The valuations of most bond markets are close to, or at, record highs.

Central bankers like to believe that it’s impossible to identify bubbles before they burst. With all the respect due to them – i.e. none whatsoever – that is nonsense. It was evident to us and many others in early 2000 that the market had got ahead of itself. Moonrock Radio simply had the good fortune – from the perspective of its handful of listeners, at any rate – to launch within a few weeks of, but also explicitly identify, the top.

That demo webcast also highlighted the fate of Julian Robertson, the founder of the Tiger Management hedge fund, which is instructive. Robertson had a long and successful career in fund management, but it ended under the cloud of early 2000. Robertson was forced to capitulate on the old economy value stocks he owned – and he sold out at the worst time in history, just as those same stocks were on the verge of bouncing back. But he was also too early in shorting dotcom stocks. He missed the top of the market by just a matter of weeks. If he had been later to the game, he might have made out like a bandit from Nasdaq’s collapse after March 2000. As it is, he was whipsawed on both sides. He sold out his value stocks too soon, and he was also too soon in shorting the TMT sector. Moral of the tale ? Never use leverage if you can avoid it. And never make your solvency dependent on your ability to time the market, because for 99.999% of investors, market timing is impossible.

We humbly submit this may soon be one of the best times in history to be a value investor – whether in relative, or absolute terms. We may be wrong – QE and ZIRP have been with us for over 10 whole years now – but we sense a disturbance in the force, as the Fed continues to hike, and bond yields and stocks creak and fragment under the accumulated pressure of an at least decade-long foray into absurdity.

In the days of ancient Rome, it is said that during a triumphal procession, a military commander would be accompanied by an Auriga – a slave who would stand behind him, whispering in his ear Memento homo: remember, you too are mortal.

Someday, perhaps quite soon, this bull market in everything is going to end – if that process hasn’t indeed already begun. Now is probably a good time to be highly discerning – to be concentrating on stocks possessing what Benjamin Graham would have called a “margin of safety”. If many of those stocks are to be found outside the US market pressure cooker, so be it.

Last word this week should probably go, then, to Warren Buffett:

“Cash combined with courage in a crisis is priceless.”

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price