Many investors claim to be value investors, but what do they really mean by the term ?

Value is somewhat subjective, and it’s to some extent in the eye of the beholder. Your definition of value and ours are likely to be somewhat different. Human nature is like that. We have different preferences, different risk tolerances, different objectives.

But we all want a good deal.

Along the continuum of investing strategies, ‘deep value’ sits at one end: it is what Warren Buffett once described as ‘cigar butt’ investing – a cigar butt found on the street that has only one puff left in it. It may not offer much of a smoke, “but the bargain purchase will make that puff all profit”.

Benjamin Graham, the spiritual father of value investing, recommended a particular type of ‘deep value’ opportunity in the form of so-called ‘net net’ stocks. A ‘net net’ stock is one where a company’s net cash and liquid assets add up to more than the entire market capitalisation of the company. In effect, you’re getting the business for free.

Two separate studies of ‘net nets’ point to the returns available from value investing.

The first, conducted by Professor Henry Oppenheimer across the US stock market between 1970 and 1983 (‘Ben Graham’s net current asset values: a performance update’) showed some impressive results. Whereas the market itself returned 11.5% per annum over the period in question, net net stocks returned 29.4% per annum. Almost three times as much.

The second, conducted by the behavioural economist James Montier, across global markets between 1985 and 2007, saw the markets themselves deliver an annual return of 17%. Net net stocks, however, returned 35% – almost twice as much. Perhaps there could be something behind deep value investing ?

One of the best exponents of deep value investing we know is the US manager Dave Iben of Kopernik Global Investors. When we first heard Iben speak at a meeting in London we were struck by a consistent refrain of what he looks for in an investment:

“I want half off.”

Whatever he’s considering buying, he wants to buy at a discount. The minimum discount he’s willing to accept is 50%. And if whatever he’s buying is in a risky market – like, say, Russia (assuming he can even access the market in the first place) – he wants even more off – perhaps as much as 80% or 90% versus ‘fair value’. So although the quality of these investments may be a little questionable, the deep discount at which they are sometimes available amounts to a margin of safety, of sorts.

And the biggest risk associated with ‘deep value’ relates to quality. A ‘deep value’ business may well be cheap, but it may also be cheap for a reason. A ‘deep value’ business runs the risk of turning into a ‘value trap’ – its shares never end up recovering toward a share price consistent with an investor’s assessment of its fair value. Capital invested in a ‘value trap’ never manages to escape from a fundamentally poorly performing company. Value traps are the stock market’s equivalent of black holes.

‘Growth’ sits at the other end of the scale. A ‘growth’ stock is widely perceived to be a better investment because the company’s revenues (if not its profits) are growing strongly. It is typically in a sexy ‘growth’ sector, like biotechnology, alternative energy, or fintech. Growth investors are essentially momentum investors – for as long as the stock price is rising, growth investors are more than happy to chug along with it. The biggest risk associated with ‘growth’ stocks is that that growth suddenly goes into reverse. Company revenues stop growing as quickly as they have in the past, or – heaven forbid – they go into reverse. Internet stocks were the classic example of growth stocks during the mid- to late-90s. Companies without profits and in many cases without even revenues could justify pretty much any valuation, on the grounds that they were growing so quickly they could ‘grow into’ those elevated valuations over time. It was important for growth investors simply to stake their claim and exploit ‘first mover advantage’. That was the theory, anyway.

One of the more notorious examples of a growth stock advocate was Jim Cramer of financial website TheStreet.com in February 2000. Delivering the keynote speech at the 6th Annual Internet and Electronic Conference and Exposition in New York, Cramer named 10 technology and internet companies and then issued the following recommendation:

“We are buying some of every one of these this morning as I give this speech. We buy them every day, particularly if they are down, which, no surprise given what they do, is very rare. And we will keep doing so until this period is over – and it is very far from ending. Heck, people are just learning these stories on Wall Street, and the more they come to learn, the more they love and own! Most of these companies don’t even have earnings per share, so we won’t have to be constrained by that methodology for quarters to come.”

Famous last words.

It turns out that Cramer inadvertently nailed the top of the first Internet boom. His speech was delivered within a month of Nasdaq’s March 2000 high. How Nasdaq subsequently performed is shown in the chart below. Nasdaq went on to fall by 80% over the next two years. Growth investing comes at a price. Or as Warren Buffett put it, it is difficult to buy what is popular and do well.

Nasdaq Composite Index, 2000 – 2009

Why Buffett isn’t a value investor

Between deep value on one hand and growth on the other lie a selection of value strategies. A few years ago we attended the London Value Investor Conference at the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, near Parliament. 500 value managers from around the world were packed into the auditorium. The first speaker asked the floor a question: what type of investor are you ? Are you a classic ‘value’ manager ? We put our hand up, but we didn’t have much company. He then asked, are you a ‘franchise’ manager ? Almost everybody stuck their hand up. Value is clearly in the eye of the beholder.

Warren Buffett began his investment career as a value manager in the style of Benjamin Graham. Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor, first published in 1949, remains the Bible of value investing. Graham went out of his way to define investment as opposed to speculation, as follows:

“An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.”

To Graham, an investment and a ‘value’ investment were essentially the same thing. Value simply offered a greater margin of safety to the investor.

But something happened to Warren Buffett along the way. His holding company, Berkshire Hathaway, became too big for him to concentrate on value investing.

Genuine value investing has its limits.

Warren Buffett faces some major constraints. Berkshire Hathaway is now a $590 billion company by market cap. Buffett cannot realistically consider buying small or even mid-cap stocks. Even if he could, even the most outsized gains would fail to budge the needle. Berkshire Hathaway is simply too big.

As Berkshire grew, Buffett was forced to shift his emphasis from Benjamin Graham-style value to what we might call ‘franchise’ value instead: businesses that enjoy a superior reputation with relation to their brands beyond those businesses’ plain balance sheet value. Which is another way of saying ‘growth’ stocks, since their shares are typically trading at a significant premium to their fair value. Buffett is fond of buying businesses with a “moat”: some seemingly unassailable position in the marketplace deriving from a monopoly-type market advantage. But shares in those type of businesses don’t come cheap, because almost everyone wants to own them. As he’s admitted, because of the scale of Berkshire’s business interests, Buffett now has to look for the market equivalent of elephants in order to move the dial on his investment portfolio. And as the fund manager Jim Slater was fond of saying, elephants don’t gallop. Buffett, in other words, has to compromise when it comes to paying, and potentially overpaying, to own quality businesses (in some instances, outright).

So when (almost) everyone at the London Value Conference confessed to being a ‘franchise’ manager, what they really meant was they had stopped being a ‘value’ manager – either because it’s too difficult, or because there are too few opportunities, or both.

The late Canadian value manager Peter Cundill nicely expressed this problem in his autobiography There’s always something to do. Specifically, he advised readers that

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. THE MAJORITY OF INVESTORS DO NOT POSSESS THIS CHARACTERISTIC.”

Your edge over the professionals

But this is an area in which, as an individual investor, you have an advantage over us. You don’t have to disclose your investments to anyone. You don’t have to worry about inflows and especially outflows from your fund. You don’t have to report your performance on a daily, weekly, monthly or quarterly basis to anybody. As managers of a UK regulated fund we are required to do all of the above. We’re comfortable with the slings and arrows of the market’s outrageous fortune – but our investors may not be. As Peter Cundill correctly pointed out, most investors do not necessarily possess an overabundance of patience.

Which is a shame. Because, as the keynote speakers at a recent SocGen Annual Investment Conference in London pointed out, value investing is the best performing investment strategy there is.

The following chart makes the point well. SocGen split the stock market up into three categories: value, quality income and low volatility. Value outperformed both of the other categories by some margin.

The problem lies in those awkward drawdowns, such as the one between 2007 and late 2008, when value doesn’t appear to work. But it’s all about patience. And expecting one particular strategy to work continually over time is naïve. No strategy works all of the time.

The difference between value – what we might call ‘quality’ value, as opposed to stocks that might form value traps – is that it also offers a margin of safety (another Benjamin Graham coinage). Provided you’ve done your research properly, a true ‘quality value’ stock gets even more attractive as and when its share price falls. But a typical ‘growth’ stock – especially one bought at a significant premium to its fair value – doesn’t necessarily get any more attractive as its share price gets weaker. If it’s been bid up to some ridiculous overvaluation by excited growth investors, its share price decline can be massive and can last for years. Bear in mind the performance of Nasdaq after Jim Cramer’s contrarian recommendation of internet stocks cited above.

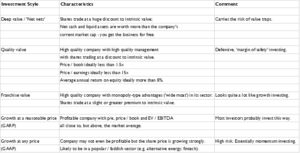

So value clearly means different things to different people. Our ‘take’ on the various sub-types of value and growth investing is shown in the table below:

One facet of value investing that reinforces the requirement for patience is the nature of the catalyst that will come to trigger all of that ‘hidden’ value to be recognised by the market.

Benjamin Graham was himself asked this question at a congressional hearing, before the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, in 1955:

The Chairman: “One other question.. When you find a special situation and you decide, just for illustration, that you can buy for $10 and it is worth $30, and you take a position, and then you cannot realize it until a lot of other people decide it is worth $30, how is that process brought about – by advertising, or what happens ?”

Benjamin Graham: “That is one of the mysteries of our business, and it is a mystery to me as well as to everybody else. We know from experience that eventually the market catches up with value. It realizes it in one way or another.”

In this respect, it might fairly be said that all genuine value investors come early to the party. They seek to acquire stakes in undervalued businesses before the market wakes up to their real worth. Sometimes well before. The nature of the catalyst to unlock that “hidden” value is never entirely clear. We just know that if a good value manager has done his homework, as opposed to falling in love with a value trap, that genuine value will be rewarded, in time. As Jeff Goldblum’s Dr. Malcolm says in Jurassic Park: nature finds a way.

But because that way is not always immediate, or obvious, the financial columnist Jonathan Davis is exactly right when he observes that

“Periods of excruciating short term underperformance are a burden that all genuine value investors have to endure.”

Or as the value manager Richard Oldfield puts it, in a phrase which became the title of his autobiography, successful value investing is Simple but not easy.

One thing that leaps out from Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor is that investors can expose themselves to significant risks by overpaying – even for high quality businesses. Quality, like value, is subjective – but both characteristics are impacted by extremes in price. It might be worth paying over 10 times book for shares in pharmaceutical companies, but we personally doubt it. As a ‘quality value’ investor there are limits in terms of what we’re willing to pay up to own anything. And there are certain types of stocks that we’re simply never going to buy – at least, not unless they trade at levels denoting a Benjamin Graham-style margin of safety. Pharmaceutical companies with reams of small font litigation risks, for example, are unlikely ever to attract us.

Beware the law of unintended consequences

Perhaps the biggest threat facing investors today is not corporate malfeasance or simple underperformance, but rather the malign impact of the Big State itself. Observe the health of the global energy, fuel and food sectors for more.

The painful and self-destructive history of government intervention is well told in Robert Schuettinger and Eamonn Butler’s excellent history Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls. The clue is in the title. You can download a PDF copy of this brilliant book here.

David Meiselman, in his foreword to Forty Centuries, raises an intriguing question:

“What, then, have price controls achieved in the recurrent struggle to restrain inflation and overcome shortages? The historical record is a grimly uniform sequence of repeated failure. Indeed, there is not a single episode where price controls have worked to stop inflation or cure shortages. Instead of curbing inflation, price controls add other complications to the inflation disease, such as black markets and shortages that reflect the waste and misallocation of resources caused by the price controls themselves. Instead of eliminating shortages, price controls cause or worsen shortages. By giving producers and consumers the wrong signals because “low” prices to producers limit supply and “low” prices to consumers stimulate demand, price controls widen the gap between supply and demand.

“Despite the clear lessons of history, many governments and public officials still hold the erroneous belief that price controls can and do control inflation. They thereby pursue monetary and fiscal policies that cause inflation, convinced that the inevitable cannot happen. When the inevitable does happen, public policy fails and hopes are dashed. Blunders mount, and faith in governments and government officials whose policies caused the mess declines. Political and economic freedoms are impaired and general civility suffers.”

Lastly, a word on diversification, geographic and otherwise. Most of us are guilty of ‘home country bias’ when it comes to investing. When you’re American, and the US markets account for 70% of the (MSCI) global index, that home country bias is understandable.

But the merits of classic Benjamin Graham-style value are undeniable, especially overseas, and over the longer run. It simply makes more sense to have a broader opportunity set of potential investments. In this letter, we’ve examined the attributes of what you should probably own. More to the point, we’ve taken a look at the attributes of what you probably shouldn’t own, and why you shouldn’t own them. Generalised central bank incompetence – not least tightening monetary policy in the face of a vicious recession – offers us a useful opportunity to diversify away from defensive stocks that aren’t really defensive at all, in favour of inexpensive stocks, from around the world, that almost certainly are.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Many investors claim to be value investors, but what do they really mean by the term ?

Value is somewhat subjective, and it’s to some extent in the eye of the beholder. Your definition of value and ours are likely to be somewhat different. Human nature is like that. We have different preferences, different risk tolerances, different objectives.

But we all want a good deal.

Along the continuum of investing strategies, ‘deep value’ sits at one end: it is what Warren Buffett once described as ‘cigar butt’ investing – a cigar butt found on the street that has only one puff left in it. It may not offer much of a smoke, “but the bargain purchase will make that puff all profit”.

Benjamin Graham, the spiritual father of value investing, recommended a particular type of ‘deep value’ opportunity in the form of so-called ‘net net’ stocks. A ‘net net’ stock is one where a company’s net cash and liquid assets add up to more than the entire market capitalisation of the company. In effect, you’re getting the business for free.

Two separate studies of ‘net nets’ point to the returns available from value investing.

The first, conducted by Professor Henry Oppenheimer across the US stock market between 1970 and 1983 (‘Ben Graham’s net current asset values: a performance update’) showed some impressive results. Whereas the market itself returned 11.5% per annum over the period in question, net net stocks returned 29.4% per annum. Almost three times as much.

The second, conducted by the behavioural economist James Montier, across global markets between 1985 and 2007, saw the markets themselves deliver an annual return of 17%. Net net stocks, however, returned 35% – almost twice as much. Perhaps there could be something behind deep value investing ?

One of the best exponents of deep value investing we know is the US manager Dave Iben of Kopernik Global Investors. When we first heard Iben speak at a meeting in London we were struck by a consistent refrain of what he looks for in an investment:

“I want half off.”

Whatever he’s considering buying, he wants to buy at a discount. The minimum discount he’s willing to accept is 50%. And if whatever he’s buying is in a risky market – like, say, Russia (assuming he can even access the market in the first place) – he wants even more off – perhaps as much as 80% or 90% versus ‘fair value’. So although the quality of these investments may be a little questionable, the deep discount at which they are sometimes available amounts to a margin of safety, of sorts.

And the biggest risk associated with ‘deep value’ relates to quality. A ‘deep value’ business may well be cheap, but it may also be cheap for a reason. A ‘deep value’ business runs the risk of turning into a ‘value trap’ – its shares never end up recovering toward a share price consistent with an investor’s assessment of its fair value. Capital invested in a ‘value trap’ never manages to escape from a fundamentally poorly performing company. Value traps are the stock market’s equivalent of black holes.

‘Growth’ sits at the other end of the scale. A ‘growth’ stock is widely perceived to be a better investment because the company’s revenues (if not its profits) are growing strongly. It is typically in a sexy ‘growth’ sector, like biotechnology, alternative energy, or fintech. Growth investors are essentially momentum investors – for as long as the stock price is rising, growth investors are more than happy to chug along with it. The biggest risk associated with ‘growth’ stocks is that that growth suddenly goes into reverse. Company revenues stop growing as quickly as they have in the past, or – heaven forbid – they go into reverse. Internet stocks were the classic example of growth stocks during the mid- to late-90s. Companies without profits and in many cases without even revenues could justify pretty much any valuation, on the grounds that they were growing so quickly they could ‘grow into’ those elevated valuations over time. It was important for growth investors simply to stake their claim and exploit ‘first mover advantage’. That was the theory, anyway.

One of the more notorious examples of a growth stock advocate was Jim Cramer of financial website TheStreet.com in February 2000. Delivering the keynote speech at the 6th Annual Internet and Electronic Conference and Exposition in New York, Cramer named 10 technology and internet companies and then issued the following recommendation:

“We are buying some of every one of these this morning as I give this speech. We buy them every day, particularly if they are down, which, no surprise given what they do, is very rare. And we will keep doing so until this period is over – and it is very far from ending. Heck, people are just learning these stories on Wall Street, and the more they come to learn, the more they love and own! Most of these companies don’t even have earnings per share, so we won’t have to be constrained by that methodology for quarters to come.”

Famous last words.

It turns out that Cramer inadvertently nailed the top of the first Internet boom. His speech was delivered within a month of Nasdaq’s March 2000 high. How Nasdaq subsequently performed is shown in the chart below. Nasdaq went on to fall by 80% over the next two years. Growth investing comes at a price. Or as Warren Buffett put it, it is difficult to buy what is popular and do well.

Nasdaq Composite Index, 2000 – 2009

Why Buffett isn’t a value investor

Between deep value on one hand and growth on the other lie a selection of value strategies. A few years ago we attended the London Value Investor Conference at the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre, near Parliament. 500 value managers from around the world were packed into the auditorium. The first speaker asked the floor a question: what type of investor are you ? Are you a classic ‘value’ manager ? We put our hand up, but we didn’t have much company. He then asked, are you a ‘franchise’ manager ? Almost everybody stuck their hand up. Value is clearly in the eye of the beholder.

Warren Buffett began his investment career as a value manager in the style of Benjamin Graham. Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor, first published in 1949, remains the Bible of value investing. Graham went out of his way to define investment as opposed to speculation, as follows:

“An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.”

To Graham, an investment and a ‘value’ investment were essentially the same thing. Value simply offered a greater margin of safety to the investor.

But something happened to Warren Buffett along the way. His holding company, Berkshire Hathaway, became too big for him to concentrate on value investing.

Genuine value investing has its limits.

Warren Buffett faces some major constraints. Berkshire Hathaway is now a $590 billion company by market cap. Buffett cannot realistically consider buying small or even mid-cap stocks. Even if he could, even the most outsized gains would fail to budge the needle. Berkshire Hathaway is simply too big.

As Berkshire grew, Buffett was forced to shift his emphasis from Benjamin Graham-style value to what we might call ‘franchise’ value instead: businesses that enjoy a superior reputation with relation to their brands beyond those businesses’ plain balance sheet value. Which is another way of saying ‘growth’ stocks, since their shares are typically trading at a significant premium to their fair value. Buffett is fond of buying businesses with a “moat”: some seemingly unassailable position in the marketplace deriving from a monopoly-type market advantage. But shares in those type of businesses don’t come cheap, because almost everyone wants to own them. As he’s admitted, because of the scale of Berkshire’s business interests, Buffett now has to look for the market equivalent of elephants in order to move the dial on his investment portfolio. And as the fund manager Jim Slater was fond of saying, elephants don’t gallop. Buffett, in other words, has to compromise when it comes to paying, and potentially overpaying, to own quality businesses (in some instances, outright).

So when (almost) everyone at the London Value Conference confessed to being a ‘franchise’ manager, what they really meant was they had stopped being a ‘value’ manager – either because it’s too difficult, or because there are too few opportunities, or both.

The late Canadian value manager Peter Cundill nicely expressed this problem in his autobiography There’s always something to do. Specifically, he advised readers that

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. THE MAJORITY OF INVESTORS DO NOT POSSESS THIS CHARACTERISTIC.”

Your edge over the professionals

But this is an area in which, as an individual investor, you have an advantage over us. You don’t have to disclose your investments to anyone. You don’t have to worry about inflows and especially outflows from your fund. You don’t have to report your performance on a daily, weekly, monthly or quarterly basis to anybody. As managers of a UK regulated fund we are required to do all of the above. We’re comfortable with the slings and arrows of the market’s outrageous fortune – but our investors may not be. As Peter Cundill correctly pointed out, most investors do not necessarily possess an overabundance of patience.

Which is a shame. Because, as the keynote speakers at a recent SocGen Annual Investment Conference in London pointed out, value investing is the best performing investment strategy there is.

The following chart makes the point well. SocGen split the stock market up into three categories: value, quality income and low volatility. Value outperformed both of the other categories by some margin.

The problem lies in those awkward drawdowns, such as the one between 2007 and late 2008, when value doesn’t appear to work. But it’s all about patience. And expecting one particular strategy to work continually over time is naïve. No strategy works all of the time.

The difference between value – what we might call ‘quality’ value, as opposed to stocks that might form value traps – is that it also offers a margin of safety (another Benjamin Graham coinage). Provided you’ve done your research properly, a true ‘quality value’ stock gets even more attractive as and when its share price falls. But a typical ‘growth’ stock – especially one bought at a significant premium to its fair value – doesn’t necessarily get any more attractive as its share price gets weaker. If it’s been bid up to some ridiculous overvaluation by excited growth investors, its share price decline can be massive and can last for years. Bear in mind the performance of Nasdaq after Jim Cramer’s contrarian recommendation of internet stocks cited above.

So value clearly means different things to different people. Our ‘take’ on the various sub-types of value and growth investing is shown in the table below:

One facet of value investing that reinforces the requirement for patience is the nature of the catalyst that will come to trigger all of that ‘hidden’ value to be recognised by the market.

Benjamin Graham was himself asked this question at a congressional hearing, before the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, in 1955:

The Chairman: “One other question.. When you find a special situation and you decide, just for illustration, that you can buy for $10 and it is worth $30, and you take a position, and then you cannot realize it until a lot of other people decide it is worth $30, how is that process brought about – by advertising, or what happens ?”

Benjamin Graham: “That is one of the mysteries of our business, and it is a mystery to me as well as to everybody else. We know from experience that eventually the market catches up with value. It realizes it in one way or another.”

In this respect, it might fairly be said that all genuine value investors come early to the party. They seek to acquire stakes in undervalued businesses before the market wakes up to their real worth. Sometimes well before. The nature of the catalyst to unlock that “hidden” value is never entirely clear. We just know that if a good value manager has done his homework, as opposed to falling in love with a value trap, that genuine value will be rewarded, in time. As Jeff Goldblum’s Dr. Malcolm says in Jurassic Park: nature finds a way.

But because that way is not always immediate, or obvious, the financial columnist Jonathan Davis is exactly right when he observes that

“Periods of excruciating short term underperformance are a burden that all genuine value investors have to endure.”

Or as the value manager Richard Oldfield puts it, in a phrase which became the title of his autobiography, successful value investing is Simple but not easy.

One thing that leaps out from Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor is that investors can expose themselves to significant risks by overpaying – even for high quality businesses. Quality, like value, is subjective – but both characteristics are impacted by extremes in price. It might be worth paying over 10 times book for shares in pharmaceutical companies, but we personally doubt it. As a ‘quality value’ investor there are limits in terms of what we’re willing to pay up to own anything. And there are certain types of stocks that we’re simply never going to buy – at least, not unless they trade at levels denoting a Benjamin Graham-style margin of safety. Pharmaceutical companies with reams of small font litigation risks, for example, are unlikely ever to attract us.

Beware the law of unintended consequences

Perhaps the biggest threat facing investors today is not corporate malfeasance or simple underperformance, but rather the malign impact of the Big State itself. Observe the health of the global energy, fuel and food sectors for more.

The painful and self-destructive history of government intervention is well told in Robert Schuettinger and Eamonn Butler’s excellent history Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls. The clue is in the title. You can download a PDF copy of this brilliant book here.

David Meiselman, in his foreword to Forty Centuries, raises an intriguing question:

“What, then, have price controls achieved in the recurrent struggle to restrain inflation and overcome shortages? The historical record is a grimly uniform sequence of repeated failure. Indeed, there is not a single episode where price controls have worked to stop inflation or cure shortages. Instead of curbing inflation, price controls add other complications to the inflation disease, such as black markets and shortages that reflect the waste and misallocation of resources caused by the price controls themselves. Instead of eliminating shortages, price controls cause or worsen shortages. By giving producers and consumers the wrong signals because “low” prices to producers limit supply and “low” prices to consumers stimulate demand, price controls widen the gap between supply and demand.

“Despite the clear lessons of history, many governments and public officials still hold the erroneous belief that price controls can and do control inflation. They thereby pursue monetary and fiscal policies that cause inflation, convinced that the inevitable cannot happen. When the inevitable does happen, public policy fails and hopes are dashed. Blunders mount, and faith in governments and government officials whose policies caused the mess declines. Political and economic freedoms are impaired and general civility suffers.”

Lastly, a word on diversification, geographic and otherwise. Most of us are guilty of ‘home country bias’ when it comes to investing. When you’re American, and the US markets account for 70% of the (MSCI) global index, that home country bias is understandable.

But the merits of classic Benjamin Graham-style value are undeniable, especially overseas, and over the longer run. It simply makes more sense to have a broader opportunity set of potential investments. In this letter, we’ve examined the attributes of what you should probably own. More to the point, we’ve taken a look at the attributes of what you probably shouldn’t own, and why you shouldn’t own them. Generalised central bank incompetence – not least tightening monetary policy in the face of a vicious recession – offers us a useful opportunity to diversify away from defensive stocks that aren’t really defensive at all, in favour of inexpensive stocks, from around the world, that almost certainly are.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price