“Here’s a list,” said Warren Buffett to a group of friends in September 1999, “of 129 airlines that in the past 20 years filed for bankruptcy. Continental was smart enough to make that list twice. As of 1992, in fact – though the picture would have improved since then – the money that had been made since the dawn of aviation by all of this country’s airline companies was zero. Absolutely zero.

“Sizing all this up, I like to think that if I’d been at Kitty Hawk in 1903 when Orville Wright took off, I would have been farsighted enough, and public-spirited enough – I owed this to future capitalists – to shoot him down. I mean, Karl Marx couldn’t have done as much damage to capitalists as Orville did.”

You can read the full transcript of his typically witty presentation here.

In the fourth quarter of 2016, Buffett’s holding company, Berkshire Hathaway – which has just posted a $43.8 billion loss for the second quarter of 2022 – purchased $2.2 billion in shares of Southwest Airlines. Berkshire also added to its holdings in American Airlines Group, Delta Air Lines and United Continental Holdings.

The timing of that 1999 presentation was instructive. Buffett was being pilloried at the time by many commentators for failing to ‘get’ the potential of technology stocks and the Internet. In her biography of Buffett, The Snowball, Alice Schroeder wrote that

“To Buffett, computers were just tunnels that enabled him to reach other people who could play bridge [like Microsoft’s Bill Gates, for example]. Buffett had a long-standing bias against technology investments, which he felt had no margin of safety.”

Buffett indeed once confessed that

“I know as much about semiconductors or integrated circuits as I do of the mating habits of the chrzaszcz [a Polish word for beetle]. We will not go into businesses where technology which is way over my head is crucial to the investment decision.”

The problem with technology stocks, even sector leaders, is their relatively limited longevity at the top. Any competitive advantage they possess is insufficiently defensible for Buffett, who likes to buy companies with “wide moats”. It’s also difficult to identify the comparatively few winners in advance, and to buy them at reasonable prices.

In 2014, Buffett called Bitcoin “a mirage” and warned investors to stay away. That earned a spirited response from Marc Andreessen, the venture capital investor and co-founder of Netscape, who said Buffett’s remarks were an example of “old white men crapping on new technology they don’t understand.”

In early 2016, Berkshire Hathaway purchased 10 million shares of Apple. That came five years after a meaningful purchase of IBM stock.

Warren Buffett has also been a long-standing critic of precious metals:

“Gold gets dug out of the ground in Africa, or someplace. Then we melt it down, dig another hole, bury it again and pay people to stand around guarding it. It has no utility. Anyone watching from Mars would be scratching their head.”

He has also written that

“Gold.. has two significant shortcomings, being neither of much use nor procreative. True, gold has some industrial and decorative utility, but the demand for these purposes is both limited and incapable of soaking up new production. Meanwhile, if you own one ounce of gold for an eternity, you will still own one ounce at its end.”

Yet between 1997 and early 1998, Berkshire Hathaway acquired 129.7 million ounces of silver. Following accusations that silver prices were being manipulated and the announcement that the CFTC (the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission) was investigating the market, Berkshire issued a brief press release relating to its purchases, stating merely that “bullion inventories have fallen very materially, because of an excess of user-demand over mine production and reclamation. Therefore, last summer [Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger] concluded that equilibrium between supply and demand was only likely to be established by a somewhat higher price.”

The Berkshire Hathaway silver purchases of 1998 do look like an attempt to corner the market. Silver prices rose from just above $4 to nearly $7 – in the process wiping out traders who were short. Among those who got dragged into the fray was Martin Armstrong of Princeton Economics International, whose business collapsed under dubious circumstances and who was later convicted for fraud and imprisoned. The damage caused by Berkshire’s mysterious foray into the silver market has shades of the infamous Hunt brothers’ silver corner of 1980.

Warren Buffett excoriates airlines for having no durable competitive advantage. Berkshire Hathaway then ends up owning $8 billion of airline stock. Warren Buffett pours scorn on technology companies for the same reason. Berkshire Hathaway then ends up owning over 8% of IBM and a meaningful stake in Apple. Warren Buffett lambasts precious metals as being the classic beneficiaries of ‘greater fool’ theory, only for Berkshire Hathaway to indulge in silver trading that may or may not have amounted to price manipulation. Is there a pattern here ?

It’s naïve to expect anybody to be consistent, especially an investor with a track record that would put anybody else’s to shame. Emerson referred to a foolish consistency as the hobgoblin of little minds; in a quotation attributed to John Maynard Keynes,

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir ?”

And we can put together all kinds of plausible justifications for Berkshire’s seemingly inconsistent investment behaviour:

- Economic conditions and industry conditions change. The bet on airlines may have been an indirect bet on the future of oil prices.

- Industry consolidation. Much of Buffett’s hostility to the airline sector predates recent consolidation in the business. By buying stock in the four largest US airlines, Berkshire was arguably making a macro call on the entire airline industry.

- Anticipation of tax cuts.

- Buffett himself wasn’t doing the buying. Now 91, it’s unlikely that Buffett is as hands-on as he once was at Berkshire Hathaway. These somewhat contentious-seeming purchases may well have been initiated by his deputies Ted Weschler and Todd Combs.

To us, the disparity between what Warren Buffett has said on the record and what Berkshire Hathaway has actually chosen to do with its capital comes down to the deep, dark and very public secret lurking at the heart of its portfolio: it’s too big to be able to do anything else.

We have written on numerous occasions about the desirability of having an edge, and how not knowing what your edge (or strategy) is amounts to not really having one. You may find it surprising that there’s no shortage of professional investors essentially piggy-backing off other investors’ holdings, as stated in 13F filings or companies’ annual reports. Interested to see what George Soros has been buying ? You can see the major holdings of Soros Fund Management LLC, for example, here.

13F filings can certainly be useful, but they also need to be handled with care. They’re quarterly reports that need to be filed with the SEC by institutional investment managers who have at least $100 million in assets under management, and they provide details of all long positions in US-listed equities. (They don’t disclose short positions.) The requirement to treat them with care is because while it’s helpful to see what a given fund manager owns, what it doesn’t tell you is when they first acquired the position, or why. There’s also the risk that by the time you elect to purchase something that another manager has already bought, he’s already sold the position – perhaps to you.

So while we’re more than a little wary of blithely hitching a ride on somebody else’s investment coat-tails, there’s still merit in taking a look at what other investors own, especially if it introduces you to opportunities that you might otherwise have overlooked. If you find something in somebody else’s portfolio that has genuine appeal, the trick is a) to conduct sufficient research whereby you can feel as strongly about the benefits (and potential liabilities) of ownership as that other investor did, and b) to exercise sufficient patience to buy that investment only when it meets your own specific investment criteria.

In terms of our own screening criteria, they’d be as follows:

- A price / book ratio of less than 1.5x

- A current and prospective price / earnings ratio of less than 15x

- Enterprise Value / Cash From Operations of less than 8x

- Cash From Operations Growth over the last 5 years

- Return on equity of at least 8% on average over recent years

- A history of buying back stock only in the right circumstances.

The first five characteristics are more or less classic Benjamin Graham-style value metrics. The sixth is no less important. The majority of stock buybacks destroy shareholder value. Company management will say that buying back stock is earnings accretive – this because they are typically compensated, by the issuance of stock options, on the basis of improvements in earnings per share. But buying back stock at well above book value lowers the return on equity of the company.

If you can find companies whose management buy back stock only when it trades below book value, hang on to those companies like a limpet. Buying back stock below book value is value accretive for the business because it increases that company’s return on equity.

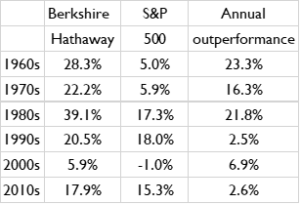

Ben Carlson has run a study of Berkshire Hathaway’s returns under Warren Buffett’s management by decade, and they make for interesting reading.

Annual returns by decade of Berkshire Hathaway versus the S&P 500, 1965-2014

While market conditions can vary, as shown by the variation in returns per decade for the S&P 500 index, it seems clear to us that there’s a generalised trend in Berkshire’s returns over time. The bigger it became, the smaller the degree of outperformance versus the market. To put it another way, the bigger Berkshire became, the more it became the market.

Warren Buffett’s no fool. He has written himself of the problem of having more capital to invest than can be profitably invested. At the 2014 Berkshire annual shareholders’ conference he admitted,

“There’s no question size is an anchor to performance..”

But if you cast an eye over the 2015 Berkshire shareholders letter you’ll see that Buffett provides two columns to show the company’s long term returns: growth in book value per share – which is the more important one, as it’s the foundation for everything else – and growth in market value per share, which is the more flattering figure, although it’s entirely out of Buffett’s hands to control, at least in the short run. He may be no fool, but he’s also no wallflower; he’d rather be a showman.

What accounts for the difference between the 23.3% annualised rate at which Berkshire was creating value for shareholders in the 1960s and the 2.6% he’s been annualising at more recently ? Size is almost certainly the answer. The evolution of Warren Buffett as an investor is essentially the history of a manager moving from ‘deep value’ (under the influence of Benjamin Graham) to ‘quality value’ to ‘franchise value’ (classic era Buffett) to ‘growth at a reasonable price’, which is probably the best way to describe Berkshire Hathaway’s investment stance today.

If you choose to invest your capital into funds, as opposed to individual stocks, it’s worth bearing in mind that the problem of the “size anchor” is just as detrimental there too. Consider the history of Fidelity’s Magellan Fund. Under Peter Lynch’s management the fund grew its assets from $18 million to $14 billion, and Lynch had the foresight – and the good fortune – to quit while he was ahead. Under his successor Jeffrey Vinik, Fidelity grew the fund to $50 billion. When do we think Magellan unitholders enjoyed their best returns ?

Why isn’t value investing more popular ? In terms of allocating your money to fund managers, there are three answers:

- Because it’s difficult. If it’s difficult for an individual to try and stay the course, it’s doubly difficult for an institutional manager – in the same way that it’s difficult for Warren Buffett to stop investors buying Berkshire Hathaway stock even as the company’s prospective returns fall from ‘amazing’ toward ‘average’. Our friend, the investment journalist and author Jonathan Davis, expresses it as follows:

“Periods of excruciating short-term underperformance are a burden that all genuine value investors have to endure.”

- Because investors, and their fund managers, are often too short-termist. If you think we exaggerate, we refer you to the two former employees of Goldman Sachs Asset Management who pointed out that at the height of the Global Financial Crisis, management demanded that certain teams report their profit and loss statements to them every hour.

- Because genuine value investing doesn’t really scale.

Human nature and fee income being what they are, most asset ‘managers’ would secretly prefer to succeed as asset ‘gatherers’ instead. But if you choose to invest with other managers, we strongly recommend that a) you favour those focusing purely on Benjamin Graham-style value and b) you favour those managers with the willingness to close to new investors before they get too big for the strategy to work.

In terms of what we might call ‘soft’ characteristics (as opposed to hard investment metrics), what do we look for in third party managers ? Self-evidently, they need to be adherents of value investing as we define it (essentially: the pursuit of high quality businesses with principled, shareholder-friendly management who are exceptional allocators of capital, and when it’s possible to buy those ‘dollar bills’ for only forty or fifty cents). But they also need to have the following attributes:

- They run independent, owner-managed businesses. Eating one’s own cooking is no guarantee of investment success – but it’s certainly a helpful statement of intent, and it aligns the interests of manager and client perfectly. Being independent of major banking or financial firms also helps. As the Chief Investment Officer of the Yale Endowment, David Swensen, pointed out in his book Pioneering Portfolio Management, investment boutiques and small, private partnerships have far fewer conflicts of interest than full service investment houses. Here, once again, size matters.

- They’re people of quality and integrity. This should go without saying.

- They have a clear and easily articulatable investment process. Simplicity trumps complexity – which is one reason why we don’t invest in macro hedge funds. There are simply far too many sources of potential problems there, not the least of which is manager error.

- They have an obvious competitive edge, not least demonstrably by dint of a proven track record of investment success. Ironically, an impressive historic track record is something that financial regulators attempt to de-emphasise in fund marketing. But without one, how on earth does one assess a manager’s performance or ability ?

- They’re focused like a laser on investment performance. Nothing else, or virtually nothing else, should matter.

- They’re asset managers and not asset gatherers. This gets to the heart of the dilemma facing individual investors looking for an institutional home for their money. Most private investors are swayed by the power of big brands. But as we see the world, it is practically a given that a small independent boutique which knows its stuff and sticks to its knitting will outperform an investment leviathan with far too many mouths to be fed sitting between you and your money.

As we’ve seen, the tree cannot grow to the sky. Growing the investment portfolio of a $700 billion by market cap. company isn’t easy. We don’t think it’s any surprise that as its capital base has grown to increasingly unwieldy proportions, Berkshire Hathaway’s investment returns have come ‘down to earth’ and lagged those of its earlier years when it was far smaller and more manageable.

Conclusion: what is appropriate for Berkshire Hathaway’s portfolio today is unlikely to be appropriate for yours. So read about the latest shareholders meeting at Berkshire with extreme care, because any message coming from it is unlikely to be for you. Whereas the managers of Berkshire are obligated to invest in abundance (think: huge market cap. companies), you can invest in scarcity instead – an investment strategy of limited capacity and therefore beyond the scope of large institutions. Where the managers of Berkshire, including Buffett himself, have sought ‘quick wins’ in trading anomalies like an undervalued silver price on a temporary basis, you can invest for the longer term, and think like an owner, rather than a mere renter of trading opportunities. Where the managers of Berkshire are obligated to invest in ‘family deals’ with similarly gigantic like-minded groups, and where they nurture relationships with established investment firms like Goldman Sachs, you can invest in independence, and with smaller scale boutique managers, or invest into small cap listed businesses, for that matter, which are well beyond the scope of investment leviathans. And whether you elect to co-invest with specialist fund managers, or directly into the shares of listed businesses on a ‘value’ basis, using the preferred investment attributes of asset managers and listed companies will help you in your quest – to achieve superior long term investment returns whilst taking less risk in the process.

We quoted Buffett last week and will repeat him here:

“Just buy something for less than it’s worth.”

In this instance, you can take him at his word.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

“Here’s a list,” said Warren Buffett to a group of friends in September 1999, “of 129 airlines that in the past 20 years filed for bankruptcy. Continental was smart enough to make that list twice. As of 1992, in fact – though the picture would have improved since then – the money that had been made since the dawn of aviation by all of this country’s airline companies was zero. Absolutely zero.

“Sizing all this up, I like to think that if I’d been at Kitty Hawk in 1903 when Orville Wright took off, I would have been farsighted enough, and public-spirited enough – I owed this to future capitalists – to shoot him down. I mean, Karl Marx couldn’t have done as much damage to capitalists as Orville did.”

You can read the full transcript of his typically witty presentation here.

In the fourth quarter of 2016, Buffett’s holding company, Berkshire Hathaway – which has just posted a $43.8 billion loss for the second quarter of 2022 – purchased $2.2 billion in shares of Southwest Airlines. Berkshire also added to its holdings in American Airlines Group, Delta Air Lines and United Continental Holdings.

The timing of that 1999 presentation was instructive. Buffett was being pilloried at the time by many commentators for failing to ‘get’ the potential of technology stocks and the Internet. In her biography of Buffett, The Snowball, Alice Schroeder wrote that

“To Buffett, computers were just tunnels that enabled him to reach other people who could play bridge [like Microsoft’s Bill Gates, for example]. Buffett had a long-standing bias against technology investments, which he felt had no margin of safety.”

Buffett indeed once confessed that

“I know as much about semiconductors or integrated circuits as I do of the mating habits of the chrzaszcz [a Polish word for beetle]. We will not go into businesses where technology which is way over my head is crucial to the investment decision.”

The problem with technology stocks, even sector leaders, is their relatively limited longevity at the top. Any competitive advantage they possess is insufficiently defensible for Buffett, who likes to buy companies with “wide moats”. It’s also difficult to identify the comparatively few winners in advance, and to buy them at reasonable prices.

In 2014, Buffett called Bitcoin “a mirage” and warned investors to stay away. That earned a spirited response from Marc Andreessen, the venture capital investor and co-founder of Netscape, who said Buffett’s remarks were an example of “old white men crapping on new technology they don’t understand.”

In early 2016, Berkshire Hathaway purchased 10 million shares of Apple. That came five years after a meaningful purchase of IBM stock.

Warren Buffett has also been a long-standing critic of precious metals:

“Gold gets dug out of the ground in Africa, or someplace. Then we melt it down, dig another hole, bury it again and pay people to stand around guarding it. It has no utility. Anyone watching from Mars would be scratching their head.”

He has also written that

“Gold.. has two significant shortcomings, being neither of much use nor procreative. True, gold has some industrial and decorative utility, but the demand for these purposes is both limited and incapable of soaking up new production. Meanwhile, if you own one ounce of gold for an eternity, you will still own one ounce at its end.”

Yet between 1997 and early 1998, Berkshire Hathaway acquired 129.7 million ounces of silver. Following accusations that silver prices were being manipulated and the announcement that the CFTC (the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission) was investigating the market, Berkshire issued a brief press release relating to its purchases, stating merely that “bullion inventories have fallen very materially, because of an excess of user-demand over mine production and reclamation. Therefore, last summer [Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger] concluded that equilibrium between supply and demand was only likely to be established by a somewhat higher price.”

The Berkshire Hathaway silver purchases of 1998 do look like an attempt to corner the market. Silver prices rose from just above $4 to nearly $7 – in the process wiping out traders who were short. Among those who got dragged into the fray was Martin Armstrong of Princeton Economics International, whose business collapsed under dubious circumstances and who was later convicted for fraud and imprisoned. The damage caused by Berkshire’s mysterious foray into the silver market has shades of the infamous Hunt brothers’ silver corner of 1980.

Warren Buffett excoriates airlines for having no durable competitive advantage. Berkshire Hathaway then ends up owning $8 billion of airline stock. Warren Buffett pours scorn on technology companies for the same reason. Berkshire Hathaway then ends up owning over 8% of IBM and a meaningful stake in Apple. Warren Buffett lambasts precious metals as being the classic beneficiaries of ‘greater fool’ theory, only for Berkshire Hathaway to indulge in silver trading that may or may not have amounted to price manipulation. Is there a pattern here ?

It’s naïve to expect anybody to be consistent, especially an investor with a track record that would put anybody else’s to shame. Emerson referred to a foolish consistency as the hobgoblin of little minds; in a quotation attributed to John Maynard Keynes,

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir ?”

And we can put together all kinds of plausible justifications for Berkshire’s seemingly inconsistent investment behaviour:

To us, the disparity between what Warren Buffett has said on the record and what Berkshire Hathaway has actually chosen to do with its capital comes down to the deep, dark and very public secret lurking at the heart of its portfolio: it’s too big to be able to do anything else.

We have written on numerous occasions about the desirability of having an edge, and how not knowing what your edge (or strategy) is amounts to not really having one. You may find it surprising that there’s no shortage of professional investors essentially piggy-backing off other investors’ holdings, as stated in 13F filings or companies’ annual reports. Interested to see what George Soros has been buying ? You can see the major holdings of Soros Fund Management LLC, for example, here.

13F filings can certainly be useful, but they also need to be handled with care. They’re quarterly reports that need to be filed with the SEC by institutional investment managers who have at least $100 million in assets under management, and they provide details of all long positions in US-listed equities. (They don’t disclose short positions.) The requirement to treat them with care is because while it’s helpful to see what a given fund manager owns, what it doesn’t tell you is when they first acquired the position, or why. There’s also the risk that by the time you elect to purchase something that another manager has already bought, he’s already sold the position – perhaps to you.

So while we’re more than a little wary of blithely hitching a ride on somebody else’s investment coat-tails, there’s still merit in taking a look at what other investors own, especially if it introduces you to opportunities that you might otherwise have overlooked. If you find something in somebody else’s portfolio that has genuine appeal, the trick is a) to conduct sufficient research whereby you can feel as strongly about the benefits (and potential liabilities) of ownership as that other investor did, and b) to exercise sufficient patience to buy that investment only when it meets your own specific investment criteria.

In terms of our own screening criteria, they’d be as follows:

The first five characteristics are more or less classic Benjamin Graham-style value metrics. The sixth is no less important. The majority of stock buybacks destroy shareholder value. Company management will say that buying back stock is earnings accretive – this because they are typically compensated, by the issuance of stock options, on the basis of improvements in earnings per share. But buying back stock at well above book value lowers the return on equity of the company.

If you can find companies whose management buy back stock only when it trades below book value, hang on to those companies like a limpet. Buying back stock below book value is value accretive for the business because it increases that company’s return on equity.

Ben Carlson has run a study of Berkshire Hathaway’s returns under Warren Buffett’s management by decade, and they make for interesting reading.

Annual returns by decade of Berkshire Hathaway versus the S&P 500, 1965-2014

While market conditions can vary, as shown by the variation in returns per decade for the S&P 500 index, it seems clear to us that there’s a generalised trend in Berkshire’s returns over time. The bigger it became, the smaller the degree of outperformance versus the market. To put it another way, the bigger Berkshire became, the more it became the market.

Warren Buffett’s no fool. He has written himself of the problem of having more capital to invest than can be profitably invested. At the 2014 Berkshire annual shareholders’ conference he admitted,

“There’s no question size is an anchor to performance..”

But if you cast an eye over the 2015 Berkshire shareholders letter you’ll see that Buffett provides two columns to show the company’s long term returns: growth in book value per share – which is the more important one, as it’s the foundation for everything else – and growth in market value per share, which is the more flattering figure, although it’s entirely out of Buffett’s hands to control, at least in the short run. He may be no fool, but he’s also no wallflower; he’d rather be a showman.

What accounts for the difference between the 23.3% annualised rate at which Berkshire was creating value for shareholders in the 1960s and the 2.6% he’s been annualising at more recently ? Size is almost certainly the answer. The evolution of Warren Buffett as an investor is essentially the history of a manager moving from ‘deep value’ (under the influence of Benjamin Graham) to ‘quality value’ to ‘franchise value’ (classic era Buffett) to ‘growth at a reasonable price’, which is probably the best way to describe Berkshire Hathaway’s investment stance today.

If you choose to invest your capital into funds, as opposed to individual stocks, it’s worth bearing in mind that the problem of the “size anchor” is just as detrimental there too. Consider the history of Fidelity’s Magellan Fund. Under Peter Lynch’s management the fund grew its assets from $18 million to $14 billion, and Lynch had the foresight – and the good fortune – to quit while he was ahead. Under his successor Jeffrey Vinik, Fidelity grew the fund to $50 billion. When do we think Magellan unitholders enjoyed their best returns ?

Why isn’t value investing more popular ? In terms of allocating your money to fund managers, there are three answers:

“Periods of excruciating short-term underperformance are a burden that all genuine value investors have to endure.”

Human nature and fee income being what they are, most asset ‘managers’ would secretly prefer to succeed as asset ‘gatherers’ instead. But if you choose to invest with other managers, we strongly recommend that a) you favour those focusing purely on Benjamin Graham-style value and b) you favour those managers with the willingness to close to new investors before they get too big for the strategy to work.

In terms of what we might call ‘soft’ characteristics (as opposed to hard investment metrics), what do we look for in third party managers ? Self-evidently, they need to be adherents of value investing as we define it (essentially: the pursuit of high quality businesses with principled, shareholder-friendly management who are exceptional allocators of capital, and when it’s possible to buy those ‘dollar bills’ for only forty or fifty cents). But they also need to have the following attributes:

As we’ve seen, the tree cannot grow to the sky. Growing the investment portfolio of a $700 billion by market cap. company isn’t easy. We don’t think it’s any surprise that as its capital base has grown to increasingly unwieldy proportions, Berkshire Hathaway’s investment returns have come ‘down to earth’ and lagged those of its earlier years when it was far smaller and more manageable.

Conclusion: what is appropriate for Berkshire Hathaway’s portfolio today is unlikely to be appropriate for yours. So read about the latest shareholders meeting at Berkshire with extreme care, because any message coming from it is unlikely to be for you. Whereas the managers of Berkshire are obligated to invest in abundance (think: huge market cap. companies), you can invest in scarcity instead – an investment strategy of limited capacity and therefore beyond the scope of large institutions. Where the managers of Berkshire, including Buffett himself, have sought ‘quick wins’ in trading anomalies like an undervalued silver price on a temporary basis, you can invest for the longer term, and think like an owner, rather than a mere renter of trading opportunities. Where the managers of Berkshire are obligated to invest in ‘family deals’ with similarly gigantic like-minded groups, and where they nurture relationships with established investment firms like Goldman Sachs, you can invest in independence, and with smaller scale boutique managers, or invest into small cap listed businesses, for that matter, which are well beyond the scope of investment leviathans. And whether you elect to co-invest with specialist fund managers, or directly into the shares of listed businesses on a ‘value’ basis, using the preferred investment attributes of asset managers and listed companies will help you in your quest – to achieve superior long term investment returns whilst taking less risk in the process.

We quoted Buffett last week and will repeat him here:

“Just buy something for less than it’s worth.”

In this instance, you can take him at his word.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price