To this day it remains the most sobering thing we have ever heard from a fellow asset manager. We first met D****** M***** back in 2000 or early 2001. He has been a manager of Japanese equity funds for over three decades. It’s a pretty small community now – most Japanese fund managers having either been carried out on a stretcher, or forced into early retirement, or into some other job altogether. That is what 25-year bear markets do for the secular prospects of fund managers exposed to them.

20 years ago, D****** gave us a warning:

“Japan has been the dress rehearsal – the rest of the world will be the main event.”

20 years ago, that struck us as an absurd thing to say. Now, from the vantage point of early 2022, after the biggest banking collapse in modern financial history, after bail-outs for all, after the most extraordinary monetary accommodation globally, after interest rates have been driven down to zero – and in some cases below it – and now with the entire world trying to deal with the aftermath of Covid and the apparent retrenchment from globalisation, it doesn’t seem so absurd any more.

Japan’s woes didn’t come out of a clear blue sky, in the same way that the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression didn’t just arrive fully formed out of nowhere. They came about on the back of a credit bubble.

As in the 1920s, the central bank was largely to blame.

Loose monetary policy by the Bank of Japan fuelled the speculative boom there in the 1980s. In 1985 this correspondent went to Japan for the first time and spent the summer touring the country. Between 1985 and 1989 Japan’s Nikkei Index tripled, and for a brief moment would account for a third of the entire world market capitalisation.

Each bubble period has its buzzword. That of 1980s Japan was “zaitech” – financial engineering, which encouraged Japanese companies to use low-interest loans to purchase equities and real estate. Japan was on the march. While at college, in addition to the works of Shakespeare and Milton, this correspondent was reading books like Clyde Prestowitz’s Trading Places: how we allowed Japan to take the lead. (A labour economist, Prestowitz had previously served under Ronald Reagan as counselor to the Secretary of Commerce.) Tired of living under the shadow of the dominant US economy, Japan in the late 1980s gave the world The Japan That Can Say No: Why Japan Will Be First Among Equals, a coming-of-age economic essay co-authored by the LDP politician Shintaro Ishihara and the chairman of Sony, Akio Morita.

Japan had soft power, too.

“Pearl Harbor didn’t work out so good, so we got you with tape decks,” jokes Mr Takagi in 1988’s Die Hard. Mitsubishi Estate was busily buying trophy assets in the US like the Rockefeller Center; Sony Corporation itself had just bought up Columbia Pictures.

The Japanese post-war economy had been built on the ferocious savings rate of Japanese households. But as Japan’s banks found themselves drowning in surplus cash, lending standards, unsurprisingly, started to soften. Easy money encourages easy attitudes and a happy-go-lucky attitude to even the prospect of risk. A succession of trade surpluses was followed by 1985’s Plaza Accord, which sought to weaken the US Dollar against the Japanese Yen (and the German Mark). The subsequent yen appreciation led to a wave of Japanese takeovers of foreign companies, including the Rockefeller and Columbia deals.

Asset prices rose, and property was a particular beneficiary of easy money and animal spirits. Prime Tokyo property prices exploded higher. Real estate in prime Tokyo neighbourhoods would become worth 350 times the value of their equivalents in Manhattan. As was widely reported at the time, the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo were rumoured to be worth as much as the entire state of California.

There was a bubble in art, too. In 1987, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers changed hands for almost $40 million, which soon looked like a steal compared to his Doctor Gachet, which sold for $82.5 million. (It’s not even a pleasant-looking painting.) But as long as asset prices rose, everybody was happy.

And then asset prices stopped rising.

Japan learnt what every country that experiences heady speculative mania and leverage always learns: that leverage in reverse is a bitch.

The stock market collapsed. The property market collapsed. Since these twin asset classes stood as collateral for trillions of yen in loans, the banking sector followed them down. Premium property prices in Tokyo’s Ginza business district would go on to fall, from peak to trough, by 99 percent. In an ominous precedent for what would happen throughout the West roughly 20 years later, Japan refused to let most of its heavily indebted banks and corporations fail. They would be bailed out instead (this correspondent joined one of them in 1991 – Sakura Bank, itself the product of a merger between the Mitsui and Taiyo Kobe banks). After the bubble burst, Japan would introduce the then-novelties of near-zero interest rates, quantitative easing, and numerous currency-weakening interventions, all in the cause of reflation.

A recent letter to the Financial Times from Mr Takashi Ito of Tokyo bridges the gap between that time and our own:

“Sir, ‘Can the Fed prevent Japanese-style deflation, a period of falling prices associated with economic stagnation, from taking hold ?’ is a common refrain nowadays.

“The US Federal Reserve’s obsession with Japan is pretty disastrous. First, Alan Greenspan opened the taps wide for too long, fearing Japanese-style deflation, which fuelled the housing bubble that led to the recent financial crisis. Now, fearing the lost decade plus, the Fed is probably going to keep easing until some different but unpleasant outcome is the result. Stagflation perhaps, or hyperinflation ?

“This is so ironic, because for so long people have sneered at the Japanese for their inability to steer their economy to recovery. Perhaps because they have sneered so much, it is no longer possible to admit that after a huge housing bubble bursts, there is nothing to do except suffer many years of economic indignity.

“The fixation with Japan was not helpful during Mr Greenspan’s watch, nor I fear will it be of much use this time. The Japanese may be different, but they were not stupid.”

Whereas the Japan of the 1980s was brash and bullish and ready to take on the world, the Japan of today is more reflective, even self-effacing. This can represent something of a challenge to visitors without a keen grasp of the language – think Bill Murray’s near-constant bafflement in Lost in Translation, which is practically a documentary about the strangeness of Japanese culture.

After one investment meeting we recently attended in Japan, at an Osaka-based manufacturer of rubber and plastic products, shortly before Covid closed the borders, the company director explained recent activities. The last two quarters had been a little disappointing, mainly due to the company spending more than anticipated on the development of a new business line. This expenditure had depressed results for the prior year but its impact would largely fall out of the company’s results for the coming fiscal year and the project was anticipated to start generating income shortly. Nevertheless, the company’s official forecast for sales and earnings called for no significant increases. The fund managers with whom we were attending questioned this forecast at some length and we were given a variety of confusing answers, explaining, unconvincingly, why prospects showed no signs of improving for the coming year.

After the meeting had finished, we walked towards some 1970s-era lifts over some comparably down-at-heel carpets, probably from the 1980s. (For value investors, the seedier the corporate premises, the better: nobody likes to see corporations squandering shareholders’ capital.) Our fellow fund manager remarked that he still didn’t understand why the company’s projected figures were so low. The company director paused, smiled, and quietly said that he completely understood our optimism. He was optimistic too. The company was deliberately setting expectations low so that it could comfortably beat its targets for the coming year.

This sort of behaviour is almost exactly the polar opposite of that of the typical Anglo-Saxon company management, which cannot wait to oversell prospects for the future. In Japan today, expectations are carefully managed to the downside. This divergence in investor relations is often associated with cultural differences between East and West. We suggest that it is the underperformance of Japanese investment returns since the peak of 1989 that has produced this more cautious approach. Indeed, we see much the same level of caution regarding operational guidance and debt issuances in sectors of the broad equity market that, like Japan, are currently trading at attractive discounts versus previous peaks.

We’ve previously highlighted how commodities continue to trade at their lowest prices relative to broad stock markets since the 1950s. Within the commodity sector, we find that precious metals producers are cheap relative to their non-precious metals counterparts as highlighted by the chart, below, showing the VanEck Junior Gold Miners Index vs the broader MSCI World Commodity Producers Index.

Forbes Magazine found that on average, businesses in the S&P 500 index nearly tripled their net debt over the past decade, adding some $2.5 trillion in leverage to their balance sheets. In comparison, after suffering a prolonged bear market from 2012-2016, the gold sector now has the lowest outstanding debt levels for 25 years. It seems clear which sectors are behaving more cautiously.

Even within certain sectors, a somewhat frivolous disregard of balance sheet strength and forward guidance appears to be highly correlated to recent share price returns as opposed to their underlying operations. In the last five years, Mercedes, for example, has delivered an average ROE of 14.35%; Tesla of minus 10.8%. Tesla’s shares, however, have risen by 80% per annum over this period, far ahead of Mercedes’ 6% annual return. We suspect that the executives of Tesla and Mercedes will approach their Q1 earnings update with markedly different attitudes – attitudes completely at odds with their operations.

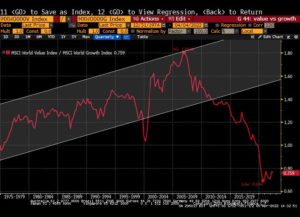

Margins this year will come under pressure from a combination of wages, rising bond yields and input costs all trending upwards. ‘Value’ stocks are currently making a one-year high against growth stocks for the first time since before the 2008 crisis. Perhaps investors are starting to focus more on cash operations and less on unrealistic future growth rates. If the chart, and mean reversion, are any guide, ‘value’ may yet have years of both relative and absolute outperformance ahead.

Value vs growth, 1975 to 2022 – the best may yet be to come ?

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

To this day it remains the most sobering thing we have ever heard from a fellow asset manager. We first met D****** M***** back in 2000 or early 2001. He has been a manager of Japanese equity funds for over three decades. It’s a pretty small community now – most Japanese fund managers having either been carried out on a stretcher, or forced into early retirement, or into some other job altogether. That is what 25-year bear markets do for the secular prospects of fund managers exposed to them.

20 years ago, D****** gave us a warning:

“Japan has been the dress rehearsal – the rest of the world will be the main event.”

20 years ago, that struck us as an absurd thing to say. Now, from the vantage point of early 2022, after the biggest banking collapse in modern financial history, after bail-outs for all, after the most extraordinary monetary accommodation globally, after interest rates have been driven down to zero – and in some cases below it – and now with the entire world trying to deal with the aftermath of Covid and the apparent retrenchment from globalisation, it doesn’t seem so absurd any more.

Japan’s woes didn’t come out of a clear blue sky, in the same way that the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression didn’t just arrive fully formed out of nowhere. They came about on the back of a credit bubble.

As in the 1920s, the central bank was largely to blame.

Loose monetary policy by the Bank of Japan fuelled the speculative boom there in the 1980s. In 1985 this correspondent went to Japan for the first time and spent the summer touring the country. Between 1985 and 1989 Japan’s Nikkei Index tripled, and for a brief moment would account for a third of the entire world market capitalisation.

Each bubble period has its buzzword. That of 1980s Japan was “zaitech” – financial engineering, which encouraged Japanese companies to use low-interest loans to purchase equities and real estate. Japan was on the march. While at college, in addition to the works of Shakespeare and Milton, this correspondent was reading books like Clyde Prestowitz’s Trading Places: how we allowed Japan to take the lead. (A labour economist, Prestowitz had previously served under Ronald Reagan as counselor to the Secretary of Commerce.) Tired of living under the shadow of the dominant US economy, Japan in the late 1980s gave the world The Japan That Can Say No: Why Japan Will Be First Among Equals, a coming-of-age economic essay co-authored by the LDP politician Shintaro Ishihara and the chairman of Sony, Akio Morita.

Japan had soft power, too.

“Pearl Harbor didn’t work out so good, so we got you with tape decks,” jokes Mr Takagi in 1988’s Die Hard. Mitsubishi Estate was busily buying trophy assets in the US like the Rockefeller Center; Sony Corporation itself had just bought up Columbia Pictures.

The Japanese post-war economy had been built on the ferocious savings rate of Japanese households. But as Japan’s banks found themselves drowning in surplus cash, lending standards, unsurprisingly, started to soften. Easy money encourages easy attitudes and a happy-go-lucky attitude to even the prospect of risk. A succession of trade surpluses was followed by 1985’s Plaza Accord, which sought to weaken the US Dollar against the Japanese Yen (and the German Mark). The subsequent yen appreciation led to a wave of Japanese takeovers of foreign companies, including the Rockefeller and Columbia deals.

Asset prices rose, and property was a particular beneficiary of easy money and animal spirits. Prime Tokyo property prices exploded higher. Real estate in prime Tokyo neighbourhoods would become worth 350 times the value of their equivalents in Manhattan. As was widely reported at the time, the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo were rumoured to be worth as much as the entire state of California.

There was a bubble in art, too. In 1987, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers changed hands for almost $40 million, which soon looked like a steal compared to his Doctor Gachet, which sold for $82.5 million. (It’s not even a pleasant-looking painting.) But as long as asset prices rose, everybody was happy.

And then asset prices stopped rising.

Japan learnt what every country that experiences heady speculative mania and leverage always learns: that leverage in reverse is a bitch.

The stock market collapsed. The property market collapsed. Since these twin asset classes stood as collateral for trillions of yen in loans, the banking sector followed them down. Premium property prices in Tokyo’s Ginza business district would go on to fall, from peak to trough, by 99 percent. In an ominous precedent for what would happen throughout the West roughly 20 years later, Japan refused to let most of its heavily indebted banks and corporations fail. They would be bailed out instead (this correspondent joined one of them in 1991 – Sakura Bank, itself the product of a merger between the Mitsui and Taiyo Kobe banks). After the bubble burst, Japan would introduce the then-novelties of near-zero interest rates, quantitative easing, and numerous currency-weakening interventions, all in the cause of reflation.

A recent letter to the Financial Times from Mr Takashi Ito of Tokyo bridges the gap between that time and our own:

“Sir, ‘Can the Fed prevent Japanese-style deflation, a period of falling prices associated with economic stagnation, from taking hold ?’ is a common refrain nowadays.

“The US Federal Reserve’s obsession with Japan is pretty disastrous. First, Alan Greenspan opened the taps wide for too long, fearing Japanese-style deflation, which fuelled the housing bubble that led to the recent financial crisis. Now, fearing the lost decade plus, the Fed is probably going to keep easing until some different but unpleasant outcome is the result. Stagflation perhaps, or hyperinflation ?

“This is so ironic, because for so long people have sneered at the Japanese for their inability to steer their economy to recovery. Perhaps because they have sneered so much, it is no longer possible to admit that after a huge housing bubble bursts, there is nothing to do except suffer many years of economic indignity.

“The fixation with Japan was not helpful during Mr Greenspan’s watch, nor I fear will it be of much use this time. The Japanese may be different, but they were not stupid.”

Whereas the Japan of the 1980s was brash and bullish and ready to take on the world, the Japan of today is more reflective, even self-effacing. This can represent something of a challenge to visitors without a keen grasp of the language – think Bill Murray’s near-constant bafflement in Lost in Translation, which is practically a documentary about the strangeness of Japanese culture.

After one investment meeting we recently attended in Japan, at an Osaka-based manufacturer of rubber and plastic products, shortly before Covid closed the borders, the company director explained recent activities. The last two quarters had been a little disappointing, mainly due to the company spending more than anticipated on the development of a new business line. This expenditure had depressed results for the prior year but its impact would largely fall out of the company’s results for the coming fiscal year and the project was anticipated to start generating income shortly. Nevertheless, the company’s official forecast for sales and earnings called for no significant increases. The fund managers with whom we were attending questioned this forecast at some length and we were given a variety of confusing answers, explaining, unconvincingly, why prospects showed no signs of improving for the coming year.

After the meeting had finished, we walked towards some 1970s-era lifts over some comparably down-at-heel carpets, probably from the 1980s. (For value investors, the seedier the corporate premises, the better: nobody likes to see corporations squandering shareholders’ capital.) Our fellow fund manager remarked that he still didn’t understand why the company’s projected figures were so low. The company director paused, smiled, and quietly said that he completely understood our optimism. He was optimistic too. The company was deliberately setting expectations low so that it could comfortably beat its targets for the coming year.

This sort of behaviour is almost exactly the polar opposite of that of the typical Anglo-Saxon company management, which cannot wait to oversell prospects for the future. In Japan today, expectations are carefully managed to the downside. This divergence in investor relations is often associated with cultural differences between East and West. We suggest that it is the underperformance of Japanese investment returns since the peak of 1989 that has produced this more cautious approach. Indeed, we see much the same level of caution regarding operational guidance and debt issuances in sectors of the broad equity market that, like Japan, are currently trading at attractive discounts versus previous peaks.

We’ve previously highlighted how commodities continue to trade at their lowest prices relative to broad stock markets since the 1950s. Within the commodity sector, we find that precious metals producers are cheap relative to their non-precious metals counterparts as highlighted by the chart, below, showing the VanEck Junior Gold Miners Index vs the broader MSCI World Commodity Producers Index.

Forbes Magazine found that on average, businesses in the S&P 500 index nearly tripled their net debt over the past decade, adding some $2.5 trillion in leverage to their balance sheets. In comparison, after suffering a prolonged bear market from 2012-2016, the gold sector now has the lowest outstanding debt levels for 25 years. It seems clear which sectors are behaving more cautiously.

Even within certain sectors, a somewhat frivolous disregard of balance sheet strength and forward guidance appears to be highly correlated to recent share price returns as opposed to their underlying operations. In the last five years, Mercedes, for example, has delivered an average ROE of 14.35%; Tesla of minus 10.8%. Tesla’s shares, however, have risen by 80% per annum over this period, far ahead of Mercedes’ 6% annual return. We suspect that the executives of Tesla and Mercedes will approach their Q1 earnings update with markedly different attitudes – attitudes completely at odds with their operations.

Margins this year will come under pressure from a combination of wages, rising bond yields and input costs all trending upwards. ‘Value’ stocks are currently making a one-year high against growth stocks for the first time since before the 2008 crisis. Perhaps investors are starting to focus more on cash operations and less on unrealistic future growth rates. If the chart, and mean reversion, are any guide, ‘value’ may yet have years of both relative and absolute outperformance ahead.

Value vs growth, 1975 to 2022 – the best may yet be to come ?

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price