There had been warnings.

Three years beforehand, in 1963, D.C.W. Jones, a Welsh waterworks engineer, had written to the District Public Works Superintendent at Treharris. Jones cautioned that the National Coal Board appeared to be dumping slurry “similar to that which was deposited and gave so much trouble in the Quarry at Merthyr Vale, up on to the existing [coal waste] tip at the rear of the Pantglas School”. He added, “I regard it as extremely serious as the slurry is so fluid and the gradient so steep that it could not possibly stay in position in the winter time or during periods of heavy rain..”

There were many coal tips at Aberfan, but ‘tip number seven’ had been growing for eight years and had risen to a heap over 100 feet high. It lay on highly porous sandstone, above a number of streams and underwater springs.

The warnings went unheeded. The National Coal Board, nationalised in 1947, stood above the British mining industry like a colossus. In the post-war corporatist climate, miners knew better than to challenge its authority. There was an implicit understanding between the NCB and the people: make a fuss, and we will close the mines.

In the village of Aberfan at the heart of the south Wales coalfield, on Friday 21 October 1966, it had been raining for days, running into weeks.

Children at the Victorian red brick Pantglas School walked excitedly through the streets of the village, looking forward to mid-day, when their half term holiday would begin.

At 9.15 a.m., the senior school had not yet started lessons. The juniors, however, began their school day half an hour earlier, and some 240 children, aged between 4 and 11, were already at their desks.

And then the mountain hit.

The only warning the people of Aberfan had that the mountain of coal slag was on the move was a deafening vibration, like thunder, some said afterwards. Others compared it to a low-flying plane.

Over 200,000 cubic metres of sludge and liquid coal roared down the hill and over the old railway embankment, rearing thirty feet high, until it reached the village.

The first building it encountered was the junior school.

There was an emergency call to Merthyr Tydfyl Police:

“I have been asked to inform you that there has been a landslide at Pantglas. The tip has come down on the school.”

What the caller could not have known was that 116 children and 28 adults had just been buried alive.

Cliff Michelmore, for the BBC, captures just some of the shock and grief of the Aberfan tragedy in this live broadcast from the current affairs programme 24 Hours. (This young reporter’s letter home makes for even more uncomfortable reading.)

There was an inquiry – the longest inquiry in British history, lasting for 76 days. The blame for Aberfan was determined to lie squarely on the shoulders of the National Coal Board. It was, the report said,

“A terrifying tale of bungling ineptitude by many men charged with tasks for which they were totally unfitted, a failure to heed warnings, and a total lack of direction from above.”

The mountain starts to grow

An uncontrolled and now uncontrollable mountain of debt started its own relentless rise roughly 50 years ago.

US President Nixon interrupted an edition of the popular TV western on 15 August 1971, to announce to the American public that the US dollar would “temporarily” no longer be convertible into gold.

The US economy was reeling from the costs of a ‘guns and butter’ policy instituted by his predecessor Lyndon Johnson: the Vietnam War, and a ‘Great Society’ welfare program, were bankrupting the country.

The world’s most unreliable allies, the French, weren’t willing to take their US dollar losses lying down, so they began converting their depreciating dollars into gold. A run on the US’ gold reserves began. Nixon decided to stop it in its tracks.

By severing the link between gold bullion and the currency, Nixon ushered in a period in which the US currency would no longer be backed by anything more substantial than the “full faith and credit” of the US government. In the aftermath of the Nixon shock, and the collapse of the Bretton Woods currency system, which had lasted for nearly 30 years, in which all currencies were pegged to the dollar and the dollar itself pegged to gold, all currencies effectively went soft overnight. With no practical limits on the creation of currency any more, Nixon initiated a money printer’s paradise.

And the debt mountain began to swell.

In their seminal paper ‘Growth in a Time of Debt’, which you can read here, Reinhart and Rogoff taught us that once government debt exceeds 90% of a country’s GDP, alarm bells start to ring. Economies effectively go ex-growth as the cost of servicing the debt burden sucks money away from more productive enterprise and the Big State crowds out the private sector in the war for capital.

All of the major western governments are bankrupt – the only question is how, precisely, the debt mountain falls.

This is, of course, exactly what Quantitative Easing (QE) and the glide path down towards zero interest rates were meant to address.

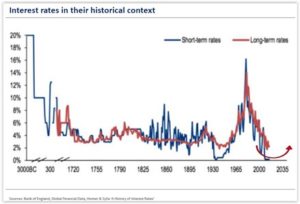

It is sometimes easy to forget just how remarkable our current financial situation is.

The chart below is a reminder.

Interest rates have never been this low before. Ever.

Forcing policy interest rates to zero – and in some cases below it – hasn’t helped the debt mountain to contract. Politicians being what politicians are, it has merely encouraged them to borrow more.

McKinsey remind us that far from experiencing deleveraging since the Global Financial Crisis, global debt actually increased by over $57 trillion. In the US, since the Nixon gold shock of 1971, “total credit market debt owed” has risen by over 35 times. GDP has inevitably lagged, growing by just 14 times over the same period.

Herbert Stein coined the appropriate adage for this growing debt mountain:

“If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

There are growing signs that we may have reached the debt market end-game.

Yields have started to rise. The US 10 year Treasury note now yields 2.9% versus its March 2020 low of 0.31%.

Monetary policy wonks have started pressing for the wider implementation of negative interest rates.

One-time IMF chief economist Kenneth Rogoff, the co-author of the 2010 paper cited above, recently published a book entitled ‘The curse of cash’. (You can perhaps gauge where our own sympathies lie given the title of our own 2015 book, ‘The war on cash’.)

In Rogoff’s book, he advocates getting rid of all high denomination dollar bills (and ultimately, all cash), notionally in the cause of fighting crime, terrorism and tax evasion.

The reality is so transparent, it’s laughable.

What Rogoff secretly, or perhaps not so secretly, supports is the introduction of solely electronic money, which would achieve two things instantaneously.

One is the ability of banks to start charging negative interest rates – a savings tax, effectively.

The other is the ability of government to monitor every single financial transaction you ever make.

By banning physical cash, which even Rogoff concedes is “coined liberty”, the authorities would be initiating a regime of Big State control so monstrous that even George Orwell could never have imagined it.

In the words of James Grant,

“Government control is not only [Rogoff’s] preferred position. It is the only position that seems to cross his mind.”

The great British parliamentarian Edmund Burke once noted that the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing. So if you take against Kenneth Rogoff’s fascistic policy recommendations, make your voice heard.

Meanwhile, the debt mountain quietly continues to grow.

Since interest rates have got as low as they can realistically go, absent a Rogoff negative rate putsch at the central banks, bond markets have now started to fret about those signs of rising inflation.

Kathleen Gaffney of Eaton Vance, which manages over $300 billion in assets, comments:

“Rates are rising from a very, very low base, which means there’s lots of downside and very little upside for bond prices.”

She has reduced the duration of her bond portfolios and started to raise cash.

“If you don’t know how to time it, and I certainly don’t, you just want to get out of the way.”

The way we choose to invest given the deteriorating fundamentals for interest rates is apophatically.

This is a word we came across in recent conversation with an old friend. It turns out we have been investing ‘apophatically’ for some time already, without realising it. You may have been, too. Here’s the context, from a recent Twitter exchange:

TP: “If Gilts were resting on a bed of nitroglycerine in 2010 [as bond fund manager Bill Gross warned at the time], they are now on octanitrocubane, firing napalm at pure antimatter.”

Our friend: “Bond shorts [short positions in government bond markets] are turning into a widow-maker, much like those short Yen and Japanese Government Bonds for lots of good reasons for nearly two decades.”

TP: “Unlike Bill Gross, I make no attempt to time this. I’m merely pointing out the horrific lack of value in bonds and the real value elsewhere.”

Our friend: “100% agree. I’ve learnt from painful experience that the best way to express macro calls is (pretentious word alert) apophatically.”

At this point another Twitter user waded in and asked for the meaning of the word (we hadn’t heard of it, either). To which our friend responded:

“Express macro concerns by avoidance rather than specifically betting on the negative macro outcome. For example: don’t own bonds.”

Chances are you’ve experienced someone speaking apophatically – apophasis being a rhetorical style particularly popular with politicians. Donald Trump is a past master at it. For example, in 2015 he said of his rival and the former CEO of Hewlett-Packard, Carly Fiorina,

“I promised that I would not say that she ran Hewlett-Packard into the ground, that she laid off tens of thousands of people, and she got viciously fired. I said I will not say it, so I will not say it.”

Used rhetorically, aphophasis is clearly a sneaky manoeuvre.

But used in an investment context, it’s altogether more down-to-earth. It essentially means: if you don’t really understand the rules of the game or if the price of something seems unsustainably high, don’t try and benefit by speculating (selling it short) because that’s too dangerous – it’s easier, and altogether less risky, just to stop playing the game instead, and go play a different game somewhere else.

Which is how we’ve regarded the global bond market for some time.

From our (value-biased and apophatic) perspective, given the distortions wrought by QE, ZIRP, NIRP and a fundamentally corrupt system, the optimal way of betting against the debt mountain is not by taking any stand against debt instruments per se, but by owning, within the context of a diversified portfolio, gold and silver, and sensibly priced commodities companies with little or no debt but high cash flow generation; this way, we’ll gain access to investments and firms that can thrive in an inflationary environment.

Speaking truth to power

John Humphreys is the former presenter of BBC Radio 4’s flagship ‘Today’ news programme. He is the closest thing that Britain has ever had to the great American news anchorman Walter Cronkite. In a recent commemoration of the Aberfan disaster before his retirement from the programme, he concluded his tribute to the little village with a quite extraordinary call to arms. He ended his piece as follows:

“When I drove here from Cardiff 50 years ago, the hills on either side of the valley were scarred with [coal refuse] tips: black and ugly and threatening. Now, as I look back down the valley from this cemetery, they’re gone: bulldozed away, or covered with grass and trees. The mining valleys of south Wales are green again.

“The river that flows beneath me was also black and dead. And now it’s clean, and children can play and fish in its shallows. And the men of these valleys, unlike their fathers, do not end their day’s work with lungs full of coal dust.

“I never met a miner who said he wanted his son to follow him down the pit. The nation owes miners a debt of gratitude for the wealth they helped create over the centuries. The mines have gone, of course, but our generation owes something different to the people of Aberfan. Respect for the courage and dignity they have shown for 50 years in dealing with unimaginable grief. But more than that.

“The children in these graves were betrayed by the men in power decades ago. Who refused to listen to their fathers when they warned them that their little school faced a mortal danger.

“If Aberfan stands for anything today, apart from unimaginable grief, it stands as a reminder of this: authority must always be challenged.”

The Aberfan tragedy was avoidable. It was certainly forecastable. The ultimate demise of the mountain of debt that overshadows all of us, and for that matter the next generation who will inherit it (or live with the aftermath of its cancellation, or being inflated away) is just as forecastable, if not necessarily easy to time. In this regard, in taking specific and meaningful action to protect one’s wealth and valuable capital, better even a year too soon than just a minute too late.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

There had been warnings.

Three years beforehand, in 1963, D.C.W. Jones, a Welsh waterworks engineer, had written to the District Public Works Superintendent at Treharris. Jones cautioned that the National Coal Board appeared to be dumping slurry “similar to that which was deposited and gave so much trouble in the Quarry at Merthyr Vale, up on to the existing [coal waste] tip at the rear of the Pantglas School”. He added, “I regard it as extremely serious as the slurry is so fluid and the gradient so steep that it could not possibly stay in position in the winter time or during periods of heavy rain..”

There were many coal tips at Aberfan, but ‘tip number seven’ had been growing for eight years and had risen to a heap over 100 feet high. It lay on highly porous sandstone, above a number of streams and underwater springs.

The warnings went unheeded. The National Coal Board, nationalised in 1947, stood above the British mining industry like a colossus. In the post-war corporatist climate, miners knew better than to challenge its authority. There was an implicit understanding between the NCB and the people: make a fuss, and we will close the mines.

In the village of Aberfan at the heart of the south Wales coalfield, on Friday 21 October 1966, it had been raining for days, running into weeks.

Children at the Victorian red brick Pantglas School walked excitedly through the streets of the village, looking forward to mid-day, when their half term holiday would begin.

At 9.15 a.m., the senior school had not yet started lessons. The juniors, however, began their school day half an hour earlier, and some 240 children, aged between 4 and 11, were already at their desks.

And then the mountain hit.

The only warning the people of Aberfan had that the mountain of coal slag was on the move was a deafening vibration, like thunder, some said afterwards. Others compared it to a low-flying plane.

Over 200,000 cubic metres of sludge and liquid coal roared down the hill and over the old railway embankment, rearing thirty feet high, until it reached the village.

The first building it encountered was the junior school.

There was an emergency call to Merthyr Tydfyl Police:

“I have been asked to inform you that there has been a landslide at Pantglas. The tip has come down on the school.”

What the caller could not have known was that 116 children and 28 adults had just been buried alive.

Cliff Michelmore, for the BBC, captures just some of the shock and grief of the Aberfan tragedy in this live broadcast from the current affairs programme 24 Hours. (This young reporter’s letter home makes for even more uncomfortable reading.)

There was an inquiry – the longest inquiry in British history, lasting for 76 days. The blame for Aberfan was determined to lie squarely on the shoulders of the National Coal Board. It was, the report said,

“A terrifying tale of bungling ineptitude by many men charged with tasks for which they were totally unfitted, a failure to heed warnings, and a total lack of direction from above.”

The mountain starts to grow

An uncontrolled and now uncontrollable mountain of debt started its own relentless rise roughly 50 years ago.

US President Nixon interrupted an edition of the popular TV western on 15 August 1971, to announce to the American public that the US dollar would “temporarily” no longer be convertible into gold.

The US economy was reeling from the costs of a ‘guns and butter’ policy instituted by his predecessor Lyndon Johnson: the Vietnam War, and a ‘Great Society’ welfare program, were bankrupting the country.

The world’s most unreliable allies, the French, weren’t willing to take their US dollar losses lying down, so they began converting their depreciating dollars into gold. A run on the US’ gold reserves began. Nixon decided to stop it in its tracks.

By severing the link between gold bullion and the currency, Nixon ushered in a period in which the US currency would no longer be backed by anything more substantial than the “full faith and credit” of the US government. In the aftermath of the Nixon shock, and the collapse of the Bretton Woods currency system, which had lasted for nearly 30 years, in which all currencies were pegged to the dollar and the dollar itself pegged to gold, all currencies effectively went soft overnight. With no practical limits on the creation of currency any more, Nixon initiated a money printer’s paradise.

And the debt mountain began to swell.

In their seminal paper ‘Growth in a Time of Debt’, which you can read here, Reinhart and Rogoff taught us that once government debt exceeds 90% of a country’s GDP, alarm bells start to ring. Economies effectively go ex-growth as the cost of servicing the debt burden sucks money away from more productive enterprise and the Big State crowds out the private sector in the war for capital.

All of the major western governments are bankrupt – the only question is how, precisely, the debt mountain falls.

This is, of course, exactly what Quantitative Easing (QE) and the glide path down towards zero interest rates were meant to address.

It is sometimes easy to forget just how remarkable our current financial situation is.

The chart below is a reminder.

Interest rates have never been this low before. Ever.

Forcing policy interest rates to zero – and in some cases below it – hasn’t helped the debt mountain to contract. Politicians being what politicians are, it has merely encouraged them to borrow more.

McKinsey remind us that far from experiencing deleveraging since the Global Financial Crisis, global debt actually increased by over $57 trillion. In the US, since the Nixon gold shock of 1971, “total credit market debt owed” has risen by over 35 times. GDP has inevitably lagged, growing by just 14 times over the same period.

Herbert Stein coined the appropriate adage for this growing debt mountain:

“If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

There are growing signs that we may have reached the debt market end-game.

Yields have started to rise. The US 10 year Treasury note now yields 2.9% versus its March 2020 low of 0.31%.

Monetary policy wonks have started pressing for the wider implementation of negative interest rates.

One-time IMF chief economist Kenneth Rogoff, the co-author of the 2010 paper cited above, recently published a book entitled ‘The curse of cash’. (You can perhaps gauge where our own sympathies lie given the title of our own 2015 book, ‘The war on cash’.)

In Rogoff’s book, he advocates getting rid of all high denomination dollar bills (and ultimately, all cash), notionally in the cause of fighting crime, terrorism and tax evasion.

The reality is so transparent, it’s laughable.

What Rogoff secretly, or perhaps not so secretly, supports is the introduction of solely electronic money, which would achieve two things instantaneously.

One is the ability of banks to start charging negative interest rates – a savings tax, effectively.

The other is the ability of government to monitor every single financial transaction you ever make.

By banning physical cash, which even Rogoff concedes is “coined liberty”, the authorities would be initiating a regime of Big State control so monstrous that even George Orwell could never have imagined it.

In the words of James Grant,

“Government control is not only [Rogoff’s] preferred position. It is the only position that seems to cross his mind.”

The great British parliamentarian Edmund Burke once noted that the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing. So if you take against Kenneth Rogoff’s fascistic policy recommendations, make your voice heard.

Meanwhile, the debt mountain quietly continues to grow.

Since interest rates have got as low as they can realistically go, absent a Rogoff negative rate putsch at the central banks, bond markets have now started to fret about those signs of rising inflation.

Kathleen Gaffney of Eaton Vance, which manages over $300 billion in assets, comments:

“Rates are rising from a very, very low base, which means there’s lots of downside and very little upside for bond prices.”

She has reduced the duration of her bond portfolios and started to raise cash.

“If you don’t know how to time it, and I certainly don’t, you just want to get out of the way.”

The way we choose to invest given the deteriorating fundamentals for interest rates is apophatically.

This is a word we came across in recent conversation with an old friend. It turns out we have been investing ‘apophatically’ for some time already, without realising it. You may have been, too. Here’s the context, from a recent Twitter exchange:

TP: “If Gilts were resting on a bed of nitroglycerine in 2010 [as bond fund manager Bill Gross warned at the time], they are now on octanitrocubane, firing napalm at pure antimatter.”

Our friend: “Bond shorts [short positions in government bond markets] are turning into a widow-maker, much like those short Yen and Japanese Government Bonds for lots of good reasons for nearly two decades.”

TP: “Unlike Bill Gross, I make no attempt to time this. I’m merely pointing out the horrific lack of value in bonds and the real value elsewhere.”

Our friend: “100% agree. I’ve learnt from painful experience that the best way to express macro calls is (pretentious word alert) apophatically.”

At this point another Twitter user waded in and asked for the meaning of the word (we hadn’t heard of it, either). To which our friend responded:

“Express macro concerns by avoidance rather than specifically betting on the negative macro outcome. For example: don’t own bonds.”

Chances are you’ve experienced someone speaking apophatically – apophasis being a rhetorical style particularly popular with politicians. Donald Trump is a past master at it. For example, in 2015 he said of his rival and the former CEO of Hewlett-Packard, Carly Fiorina,

“I promised that I would not say that she ran Hewlett-Packard into the ground, that she laid off tens of thousands of people, and she got viciously fired. I said I will not say it, so I will not say it.”

Used rhetorically, aphophasis is clearly a sneaky manoeuvre.

But used in an investment context, it’s altogether more down-to-earth. It essentially means: if you don’t really understand the rules of the game or if the price of something seems unsustainably high, don’t try and benefit by speculating (selling it short) because that’s too dangerous – it’s easier, and altogether less risky, just to stop playing the game instead, and go play a different game somewhere else.

Which is how we’ve regarded the global bond market for some time.

From our (value-biased and apophatic) perspective, given the distortions wrought by QE, ZIRP, NIRP and a fundamentally corrupt system, the optimal way of betting against the debt mountain is not by taking any stand against debt instruments per se, but by owning, within the context of a diversified portfolio, gold and silver, and sensibly priced commodities companies with little or no debt but high cash flow generation; this way, we’ll gain access to investments and firms that can thrive in an inflationary environment.

Speaking truth to power

John Humphreys is the former presenter of BBC Radio 4’s flagship ‘Today’ news programme. He is the closest thing that Britain has ever had to the great American news anchorman Walter Cronkite. In a recent commemoration of the Aberfan disaster before his retirement from the programme, he concluded his tribute to the little village with a quite extraordinary call to arms. He ended his piece as follows:

“When I drove here from Cardiff 50 years ago, the hills on either side of the valley were scarred with [coal refuse] tips: black and ugly and threatening. Now, as I look back down the valley from this cemetery, they’re gone: bulldozed away, or covered with grass and trees. The mining valleys of south Wales are green again.

“The river that flows beneath me was also black and dead. And now it’s clean, and children can play and fish in its shallows. And the men of these valleys, unlike their fathers, do not end their day’s work with lungs full of coal dust.

“I never met a miner who said he wanted his son to follow him down the pit. The nation owes miners a debt of gratitude for the wealth they helped create over the centuries. The mines have gone, of course, but our generation owes something different to the people of Aberfan. Respect for the courage and dignity they have shown for 50 years in dealing with unimaginable grief. But more than that.

“The children in these graves were betrayed by the men in power decades ago. Who refused to listen to their fathers when they warned them that their little school faced a mortal danger.

“If Aberfan stands for anything today, apart from unimaginable grief, it stands as a reminder of this: authority must always be challenged.”

The Aberfan tragedy was avoidable. It was certainly forecastable. The ultimate demise of the mountain of debt that overshadows all of us, and for that matter the next generation who will inherit it (or live with the aftermath of its cancellation, or being inflated away) is just as forecastable, if not necessarily easy to time. In this regard, in taking specific and meaningful action to protect one’s wealth and valuable capital, better even a year too soon than just a minute too late.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price