“Three financial economists examined this issue. Josef Lakonishok, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny (henceforth LSV) studied the performance of stocks investors typically consider to be growth stocks. These researchers label growth stocks as “glamour” stocks. Stocks of firms that investors typically consider to be bad firms with minimal growth prospects are labelled “value” stocks. Investors consider growth firms to be firms with growing business operations. LSV calculated the average growth rate in sales for all firms over the past five years. The 10 percent of firms with the highest average growth rates were glamour firms, whereas the firms with the lowest sales growth were value firms. Glamour or value—which stocks will be better investments over the next year? The next five years? Using data for all stocks on the New York Stock Exchange and American Stock Exchange over the period 1963–1990, LSV reported the results in Figure 8.1.3 If you bought the glamour stocks, you earned an 11.4 percent return the following year. This compares with a return of 18.7 percent for the value stocks. The average total return over a five-year period is 81.8 percent for the glamour stocks and 143.4 percent for the value stocks.”

John Vaillant’s ‘The Tiger’ is set in the far eastern Russian wilderness of a region that the Chinese call the ‘forest sea’. It tells the true-life story of an experienced trapper and poacher killed by a tiger, and of the man employed by a unit called ‘Inspection Tiger’ who is brought in to investigate. In some respects it is a “murder mystery written in snow”. It is also a study in human psychology:

“The most terrifying and important test for a human being is to be in absolute isolation…A human being is a very social creature, and ninety percent of what he does is done only because other people are watching. Alone, with no witnesses, he starts to learn about himself—who is he really ? Sometimes, this brings staggering discoveries. Because nobody’s watching, you can easily become an animal: it is not necessary to shave, or to wash, or to keep your winter quarters clean—you can live in shit and no one will see. You can shoot tigers, or choose not to shoot. You can run in fear and nobody will know. You have to have something—some force, which allows and helps you to survive without witnesses…Once you have passed the solitude test you have absolute confidence in yourself, and there is nothing that can break you afterward.”

There is something almost mythical in the challenge of contrarian investing. Because at heart, all value investing is contrarian investing. Human beings are hard-wired to seek consensus. For most of our evolutionary history, it made complete sense to be part of the crowd. To be different from the crowd, to go one’s own way, would have been fatal to our ancient ancestors. It would have meant starvation, and a quick, perhaps painful, almost certainly lonely death. In the modern world, perversely, perhaps the financial markets are one of the few places we can still forge an identity for ourselves in the wilderness – a place where we can be alone, yet remain within the crowd. In any event, contrarian investing demands that we be “alone” for much of the time. The value investor Patrick O’Shaughnessy cites the American writer and mythologist Joseph Campbell:

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.”

The business of professional value investing is doubly challenging, in that it involves not just a deep commitment to contrarian investing on the part of the manager, but on the part of his clients, too. In other words, there are two separate entities that have to be completely happy with the adoption of a non-consensual investment policy, namely portfolio manager and client. There’s an old market saying that touches on some of these psychological issues:

“If you don’t know who you are, the market is an expensive place to find out.”

It may be easy to pay lip service to contrarian investing, but maintaining that commitment in a tough market is anything but. In the words of the German military strategist Helmuth von Moltke, no battle plan survives contact with the enemy.

Here’s a fascinating real world example, sent to me by a friend in South Africa, Kokkie Kooyman, now of Denker Capital.

Imagine you are a shareholder in Warren Buffett’s legendary holding company, Berkshire Hathaway. You’ve already enjoyed some fabulous returns, having tagged along on Buffett’s coattails ever since he started his first partnership in 1956.

It is now 1975.

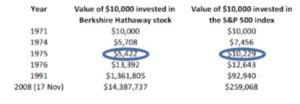

In 1971, you had $10,000 invested in Berkshire Hathaway stock. You have a friend who had an identical amount invested in the S&P 500 stock index.

Then the Arab oil embargo happens. The oil price soars from $3 a barrel to nearly $12. The stock market collapses. Berkshire is not immune. By 1974, your Berkshire shares are worth $5,708. Your friend is doing badly, but better than you – his investment is worth $7,456.

Now, in 1975, you begin to reassess your portfolio. Your friend has bounced back into the black. His grubstake in the S&P 500 is back above $10,000. But your shares in Berkshire are now almost half of what they were worth four years ago. The stock market has recovered, but your shareholding hasn’t. Ask yourself honestly. What would you have done ?

One suspects that in 1975, most investors would have bailed on Buffett. Underperformance relative to the market for one calendar year is difficult enough to stomach. But sitting through four years of relative underperformance is a really tough ask. Not many investors, we suggest, would have had the stamina.

Selling Berkshire in 1975, of course, would have been a colossal mistake, with the benefit of hindsight. Within just a year, the value of the Berkshire holding would have been above that of the S&P 500 again, and back above the level of your friend’s portfolio. And by 1991, the scale of the subsequent outperformance would have been clear to all. But ask yourself again:

Would you have sold in ’75 ?

Buffett’s mentor, Ben Graham, nicely summarised these problems with his trademark brevity:

“Individuals who cannot master their emotions are ill-suited to profit from the investment process.”

Contrarian investing today is arguably even more of a challenge because it’s damnably difficult to trust the prices of any financial assets, anywhere. How can one invest rationally when all the benchmarks associated with sound investment principles have become hopelessly distorted by outrageous levels of central bank stimulus ?

Conventional investment theory holds that the investment journey begins with the “risk-free rate”: the market interest rate available on short term government debt of the highest quality. Investors can, in theory, choose to park their money in “riskless” bank deposits or “riskless” short term government bonds. If they have a higher appetite for risk, they should be able to earn a spread above the risk-free rate by holding bonds of inferior credit quality (corporate debt, for example) or by buying listed equity investments instead.

There are at least two problems with this theory today. One is that the market interest rate is no longer set by anything approximating to a free market. It is set by government fiat. Or more accurately, it is set by central banks, acting as agents for those same governments.

The second is that courtesy of the price distortion inherent in Quantitative Easing, the risk-free returns once offered by government bonds have become return-free risks.

There is a third problem. “Risk-free” implies some kind of inherent creditworthiness. But in the Alice-Through-The-Looking-Glass investment world of 2022, government bonds now offer some of the lowest yields in recorded history even as the supply of government debt has never been higher. It is as if the laws of supply and demand have been utterly rescinded. In other words, the true credit quality of western government debt has never been lower – the exact opposite of what those all-time low (but now lately rising) yields would suggest.

With politicians throughout the West unable or unwilling to implement the hard choices and economic restructuring required to drag their economies out of a debt-soaked deflationary mire, central bankers have chosen to fill the resultant policy vacuum. But their policy options are limited to playing games with interest rates and money. Hence the universal adoption of Quantitative Easing by the US, by the UK, by Japan, by China, and now, somewhat belatedly, by the European Central Bank. In the absence of bold political action, central banks have been creating ex nihilo money and using it to buy bonds. The somewhat tenuous argument in justification of QE is that it is needed to prevent deflation. Deflation must be defeated because if it becomes entrenched, it will bankrupt heavily indebted governments. There is no evidence yet that QE has been or will be successful to this reflationary end. But there is overwhelming evidence that QE has distorted asset prices, and has driven both bond and equity markets to levels that they may well not have reached in the absence of money-printing.

Market timing is admittedly a fool’s errand, especially when trillions of central bank dollars can be conjured up and pumped into the system at a moment’s notice. Nevertheless, there is growing evidence, both anecdotal and fundamental, in favour of the market for growth stocks having already peaked.

All of which makes us despair for the growing number of individuals flooding into the market indiscriminately today, by buying passive ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds), at what are close to all-time highs. (And clearly, within a QE and now MMT world, market valuations are capable of going much higher, for much longer than anybody expects.)

But there’s buying stock markets, and then there’s buying stocks within markets. We are only interested in the latter. We make no claims for being traders. We are interested solely and uniquely in bottom-up value, wherever it can be found.

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.”

Well, nobody promised you a rose garden. Man up and go bag a tiger.

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

“Three financial economists examined this issue. Josef Lakonishok, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny (henceforth LSV) studied the performance of stocks investors typically consider to be growth stocks. These researchers label growth stocks as “glamour” stocks. Stocks of firms that investors typically consider to be bad firms with minimal growth prospects are labelled “value” stocks. Investors consider growth firms to be firms with growing business operations. LSV calculated the average growth rate in sales for all firms over the past five years. The 10 percent of firms with the highest average growth rates were glamour firms, whereas the firms with the lowest sales growth were value firms. Glamour or value—which stocks will be better investments over the next year? The next five years? Using data for all stocks on the New York Stock Exchange and American Stock Exchange over the period 1963–1990, LSV reported the results in Figure 8.1.3 If you bought the glamour stocks, you earned an 11.4 percent return the following year. This compares with a return of 18.7 percent for the value stocks. The average total return over a five-year period is 81.8 percent for the glamour stocks and 143.4 percent for the value stocks.”

John Vaillant’s ‘The Tiger’ is set in the far eastern Russian wilderness of a region that the Chinese call the ‘forest sea’. It tells the true-life story of an experienced trapper and poacher killed by a tiger, and of the man employed by a unit called ‘Inspection Tiger’ who is brought in to investigate. In some respects it is a “murder mystery written in snow”. It is also a study in human psychology:

“The most terrifying and important test for a human being is to be in absolute isolation…A human being is a very social creature, and ninety percent of what he does is done only because other people are watching. Alone, with no witnesses, he starts to learn about himself—who is he really ? Sometimes, this brings staggering discoveries. Because nobody’s watching, you can easily become an animal: it is not necessary to shave, or to wash, or to keep your winter quarters clean—you can live in shit and no one will see. You can shoot tigers, or choose not to shoot. You can run in fear and nobody will know. You have to have something—some force, which allows and helps you to survive without witnesses…Once you have passed the solitude test you have absolute confidence in yourself, and there is nothing that can break you afterward.”

There is something almost mythical in the challenge of contrarian investing. Because at heart, all value investing is contrarian investing. Human beings are hard-wired to seek consensus. For most of our evolutionary history, it made complete sense to be part of the crowd. To be different from the crowd, to go one’s own way, would have been fatal to our ancient ancestors. It would have meant starvation, and a quick, perhaps painful, almost certainly lonely death. In the modern world, perversely, perhaps the financial markets are one of the few places we can still forge an identity for ourselves in the wilderness – a place where we can be alone, yet remain within the crowd. In any event, contrarian investing demands that we be “alone” for much of the time. The value investor Patrick O’Shaughnessy cites the American writer and mythologist Joseph Campbell:

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.”

The business of professional value investing is doubly challenging, in that it involves not just a deep commitment to contrarian investing on the part of the manager, but on the part of his clients, too. In other words, there are two separate entities that have to be completely happy with the adoption of a non-consensual investment policy, namely portfolio manager and client. There’s an old market saying that touches on some of these psychological issues:

“If you don’t know who you are, the market is an expensive place to find out.”

It may be easy to pay lip service to contrarian investing, but maintaining that commitment in a tough market is anything but. In the words of the German military strategist Helmuth von Moltke, no battle plan survives contact with the enemy.

Here’s a fascinating real world example, sent to me by a friend in South Africa, Kokkie Kooyman, now of Denker Capital.

Imagine you are a shareholder in Warren Buffett’s legendary holding company, Berkshire Hathaway. You’ve already enjoyed some fabulous returns, having tagged along on Buffett’s coattails ever since he started his first partnership in 1956.

It is now 1975.

In 1971, you had $10,000 invested in Berkshire Hathaway stock. You have a friend who had an identical amount invested in the S&P 500 stock index.

Then the Arab oil embargo happens. The oil price soars from $3 a barrel to nearly $12. The stock market collapses. Berkshire is not immune. By 1974, your Berkshire shares are worth $5,708. Your friend is doing badly, but better than you – his investment is worth $7,456.

Now, in 1975, you begin to reassess your portfolio. Your friend has bounced back into the black. His grubstake in the S&P 500 is back above $10,000. But your shares in Berkshire are now almost half of what they were worth four years ago. The stock market has recovered, but your shareholding hasn’t. Ask yourself honestly. What would you have done ?

One suspects that in 1975, most investors would have bailed on Buffett. Underperformance relative to the market for one calendar year is difficult enough to stomach. But sitting through four years of relative underperformance is a really tough ask. Not many investors, we suggest, would have had the stamina.

Selling Berkshire in 1975, of course, would have been a colossal mistake, with the benefit of hindsight. Within just a year, the value of the Berkshire holding would have been above that of the S&P 500 again, and back above the level of your friend’s portfolio. And by 1991, the scale of the subsequent outperformance would have been clear to all. But ask yourself again:

Would you have sold in ’75 ?

Buffett’s mentor, Ben Graham, nicely summarised these problems with his trademark brevity:

“Individuals who cannot master their emotions are ill-suited to profit from the investment process.”

Contrarian investing today is arguably even more of a challenge because it’s damnably difficult to trust the prices of any financial assets, anywhere. How can one invest rationally when all the benchmarks associated with sound investment principles have become hopelessly distorted by outrageous levels of central bank stimulus ?

Conventional investment theory holds that the investment journey begins with the “risk-free rate”: the market interest rate available on short term government debt of the highest quality. Investors can, in theory, choose to park their money in “riskless” bank deposits or “riskless” short term government bonds. If they have a higher appetite for risk, they should be able to earn a spread above the risk-free rate by holding bonds of inferior credit quality (corporate debt, for example) or by buying listed equity investments instead.

There are at least two problems with this theory today. One is that the market interest rate is no longer set by anything approximating to a free market. It is set by government fiat. Or more accurately, it is set by central banks, acting as agents for those same governments.

The second is that courtesy of the price distortion inherent in Quantitative Easing, the risk-free returns once offered by government bonds have become return-free risks.

There is a third problem. “Risk-free” implies some kind of inherent creditworthiness. But in the Alice-Through-The-Looking-Glass investment world of 2022, government bonds now offer some of the lowest yields in recorded history even as the supply of government debt has never been higher. It is as if the laws of supply and demand have been utterly rescinded. In other words, the true credit quality of western government debt has never been lower – the exact opposite of what those all-time low (but now lately rising) yields would suggest.

With politicians throughout the West unable or unwilling to implement the hard choices and economic restructuring required to drag their economies out of a debt-soaked deflationary mire, central bankers have chosen to fill the resultant policy vacuum. But their policy options are limited to playing games with interest rates and money. Hence the universal adoption of Quantitative Easing by the US, by the UK, by Japan, by China, and now, somewhat belatedly, by the European Central Bank. In the absence of bold political action, central banks have been creating ex nihilo money and using it to buy bonds. The somewhat tenuous argument in justification of QE is that it is needed to prevent deflation. Deflation must be defeated because if it becomes entrenched, it will bankrupt heavily indebted governments. There is no evidence yet that QE has been or will be successful to this reflationary end. But there is overwhelming evidence that QE has distorted asset prices, and has driven both bond and equity markets to levels that they may well not have reached in the absence of money-printing.

Market timing is admittedly a fool’s errand, especially when trillions of central bank dollars can be conjured up and pumped into the system at a moment’s notice. Nevertheless, there is growing evidence, both anecdotal and fundamental, in favour of the market for growth stocks having already peaked.

All of which makes us despair for the growing number of individuals flooding into the market indiscriminately today, by buying passive ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds), at what are close to all-time highs. (And clearly, within a QE and now MMT world, market valuations are capable of going much higher, for much longer than anybody expects.)

But there’s buying stock markets, and then there’s buying stocks within markets. We are only interested in the latter. We make no claims for being traders. We are interested solely and uniquely in bottom-up value, wherever it can be found.

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.”

Well, nobody promised you a rose garden. Man up and go bag a tiger.

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price