“An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.”

- Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor.

“All investing is value investing, the rest is speculation.”

Get your Free

financial review

One of the inevitable facets of the investment business is that if you stick around long enough within it, you get to see everything – twice. So it is a reliable rule of thumb that every few years, breathless financial journalists will gleefully report the death of value investing. True to form, ‘The Financial Times’, just a few months into the ‘pandemic’ back in 2020, ran with one of its Big Read op-eds, ‘Does value investing still make sense ?’ The sub-head gives you the gist of the piece:

“The strategy that once worked for Keynes and Buffett has performed badly. The pandemic has compounded the pain.”

“Once” ? To our knowledge Keynes was a speculator who had to be bailed out on multiple occasions. Hunter Lewis for the Mises website corrects the popular view of Keynes as some kind of value investing legend:

“Keynes’s initial foray into investing led to a smash up. He lost everything he had unwisely borrowed and had to be bailed out by his parents, who had some inherited money but were not wealthy.

“He did not do well in the 1920s. He was taken unawares by the 1929 Crash and also by the 1937 rout. In both instances, he came perilously close to being wiped out again because of very concentrated holdings of currencies, stocks, and commodities and continuing use of leverage (as much as one pound of debt for every pound of his own). In short, Keynes was a speculator, at the same time that he criticized speculators and the “casino” atmosphere of the market. He also failed entirely to understand that the casino was fuelled by the easy money policies which he espoused..”

“Once” ? Warren Buffett’s track record at Berkshire Hathaway encompasses a more than half a century period during which shareholders enjoyed an average annual return of roughly 20%, compounding to an overall return of over 4,000,000%. We should all be so lucky to enjoy such “occasional” performance.

An FT reader then weighed in, to put the boot a little more firmly into the stomach of value investing. A John Price (no relation) of Saratoga wrote in to say:

“Reading the FT Big Read (Tuesday May 12) and the role of Benjamin Graham, who defined “value investing” in 1934, readers may not know that Graham in later years became well aware of profound changes in the availability of information and analysis, and its implications.

“In 1976, the year of his death, he wrote: “I am no longer an advocate of elaborate techniques of security analysis in order to find superior value opportunities. This was a rewarding activity when ‘Graham and Dodd’ was first published, but the situation has changed . . . Today I doubt whether such extensive efforts will generate sufficiently superior selections to justify their cost . . . I’m on the side of the Efficient Market school of thought.”

“Today, 46 years after Graham’s death, and despite years of poor returns for value stocks, the advocates of value investing are still “unshakeable in their faith that past patterns will reassert themselves”. To me, it now sounds more like a religion than a rational approach to investing !”

We must confess we were unaware of Ben Graham’s apparent deathbed conversion to the Efficient Market Hypothesis, but we still feel that Mr Price wildly overstates his case. Take those “years of poor returns for value stocks”, for example. Which years would those be, exactly ?

Let’s take the long view, again. Bank of America Merrill Lynch recently crunched the numbers for the US market over a 90 year period (1926-2015) and found that whereas growth stocks delivered average annual returns of 12.6% over the period in question, value stocks returned, on average, 17% by comparison.

Intriguingly, another FT reader, a Mr David Coombs from Corby, Northamptonshire, then weighed in, in rebuttal to Mr Price:

“I consider John Price’s suggestion that Benjamin Graham rejected the strategy of value investment towards the end of his life to be disingenuous (“Keeping faith with value investment makes no sense”, Letters, May 14).

“In the interview to which Mr Price refers, he omits the beginning of the sentence used to make his main point. Graham actually stated: “To that very limited extent I’m on the side of the ‘efficient market’ school of thought.” This changes the context somewhat.

“In the same interview Graham, when asked his recommended approach to investment, states: “The purchase of common stocks at less than their working-capital value.”

In investing, terms like ‘value’ and ‘growth’ are thrown about with abandon, as if everyone had a shared definition. Such a shared definition does not really exist. But here is ours:

A value stock is the listed equity of a company run by principled, shareholder-friendly management with a proven track record of superb asset allocation, where the equity of that company is, for whatever reason, temporarily available at a meaningful discount to its inherent worth.

Index providers tend to maintain certain metrics to distinguish between ‘value’ and ‘growth’ – measures like price to earnings, price to sales, price to book and so forth. These metrics have varying use when it comes to assessing the characteristics of a listed business. Our favourite metrics tend to focus on cash flow, given that cash, unlike earnings, is difficult to manipulate. Cash, in this context, is in fact king. If we were to pick just one metric as a helpful identifier in the cause of value investing, it would be Enterprise Value (the sum of a company’s debt and equity) relative to cashflow from operations. Invert that relationship and you get a measurement of cash flow yield. Beyond that, we simply look to avoid companies in sectors that are too problematic or otherwise expensive – banks being a good example of the former, and many fast-growing technology companies being examples of the latter. Outside these pet biases, we try to be sector-agnostic, because you just never know, and it helps to have the widest opportunity set possible. And as we regularly take pains to point out, it makes sense to avoid companies carrying high levels of debt on their balance sheet, because they simply may not make it through to the other side during environments of acute economic distress.

Value vs Growth (MSCI World Value Index / MSCI World Growth Index, 1975 – 2024)

Source: Bloomberg LLP

Nevertheless, as the chart above shows quite vividly, the relative outperformance of growth versus value (at least in terms of the composition of MSCI’s World Growth and World Value indices) has been spectacular since the ‘fever pitch’ of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. As the chart indicates, on a comparative basis, growth stocks are now even more extremely valued than they were in early 2000 at the height of the dotcom boom – and we know what happened shortly thereafter..

Which is what gives us optimism. See also this blog which reiterates the extraordinary comparative underperformance of value stocks over recent years. But as it points out, anyone with a respect for the longer term cycles of history cannot but be positive:

“We are not into calling bottoms or factor timing. But looking at history, it appears that a golden decade for value investing might be ahead. After reaching the bottom in 1904, value earned 9.99% per year above the risk free rate for the next 9 years, recovering its losses. It then continued to rally for another 7 years, earning 17.8% per year above the risk free rate.”

To bet against value now would be betting against human nature. Value stocks aren’t alone in having their deaths announced on a regular basis by the commentariat. Trend-following or momentum strategies also enjoy comparable periods of being hugely out of favour. This is because human emotions don’t fundamentally change, and so financial markets continually ebb and oscillate between extremes of greed (or euphoria) on one hand, and fear (or pessimism) on the other. For those patient investors looking for superior returns, these extreme cycles are not causes for concern but rather sources of opportunity. It is difficult to outperform the crowd when you are part of it.

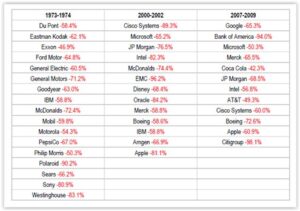

When bad things happen to “really good” companies

Source: Kopernik Global Investors, LLC

The table above is a reflection of one of our causes for concern at ‘growth’ companies – that when the tide turns, the selling pressure can become painfully acute. Those ‘tipping point’ moments are not necessarily easy to identify in advance, so our preference is not to be exposed to dangerously overpriced investments in the first place. Capital preservation, for us, always trumps the potential for fast and dramatic gains.

Back in the mid-1970s, the glamour stocks of the day were referred to as the “Nifty Fifty”. Times changed and the nomenclature changed, but the downdraft for the dotcom favourites of the early 2000s was just as severe – and during the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-9, the damage incurred by certain financial sector stocks was almost terminal.

In a recent research piece, ‘Making Plans for Nigel’, Kopernik’s founder, David Iben, draws attention to the opportunities now on offer for investors willing to take a more contrarian stance, especially in relation to the commodities sector. Like us he is an especial fan of gold, but this is more than just a gold story. As he writes,

“Let’s turn our attention to other commodities, which recently have reached generationally attractive prices. Most of them hadn’t been especially interesting since they were pushed skyward by the Chinese-driven bubble of a decade ago. They have become interesting again following their decade long decline, in absolute terms and relative to gold, followed by the recent virus-driven coup de grace.. This all paints a picture demonstrating that gold is very cheap compared to the dollar, and other fiat currencies, gold miners are very attractive relative to gold itself, many commodity prices have become very depressed in relation to gold, and commodity related companies have become quite attractive relative to the commodities they own.”

Uranium looks particularly interesting, not least given the trend towards renewables and alternative energy. As Iben observes,

“We don’t typically invest with a “catalyst in mind,” believing that attractive valuation eventually serves as its own catalyst, and having noticed that stocks usually rocket higher before people notice the catalysts. Uranium seems to be one of the rare exceptions. Catalysts have become abundant in recent months. Cameco Corp. closed MacArthur River (maybe the best mine ever). The U.S. Department of Energy stopped selling their stash, and the Russians stopped several years prior. The Kazakhs cut production once, then twice, and just announced a coronavirus related major reduction of supply. Similarly, Cameco closed its Cigar Lake mine, temporarily, due to the coronavirus. Two high-cost mines in Africa have finally closed. On the demand side, demand for electricity is down some, but Japan has reopened nine reactors and China has opened a similar number, with thirty more in various stages of planning and construction. Funds have been formed to buy and hold. Supply falls well short of demand.. Prices need to double, if not triple, to avoid shortages and multi-billion dollar reactors sitting idle.”

But as things stand, both on valuation grounds and because of the sheer scale of governmental reflationary stimulus around the world, and more recently the extent of central bank purchases (in the Ukraine-related aftermath of the freezing of Russia’s foreign reserves), gold remains our single favourite investment. In our worldview at present, all roads lead to gold. And not just gold. Our friend, the investment strategist James Ferguson, recently wrote:

“The Fed’s aggressively huge QE has been equivalent, in just 6-8 weeks, to more than half of what was done over 6 years during resolution. This time, all money measures from narrow to broad are rising steeply; broad money at a record peacetime rate.

“Bank lending is still growing too and the Fed’s $2.3 trillion loan stimulus programme has yet to begin.

“There is even evidence the Fed has been funding the Treasury directly (i.e. MMT), despite MMT having no workable policy to rein back inflation once unleashed.

“We know from past QE which assets benefit (risk-on, precious metals) and which lose out (diluted currencies, bonds). Whilst the bond market may be mesmerized by the output gap, it appears overly complacent about the magnitude and breadth of the policy intervention.

“Gold, unsurprisingly, has already advanced to the cusp of a new all-time, record high but its leveraged acolyte, silver, is obligingly at a record relative discount, so at least inflation protection is cheap.”

In other words, for portfolio insurance, portfolio diversification and currency protection, don’t limit yourself to gold.

For many years now we have lived happily with the conclusion that value investing – on our terms, at least – is the only form of investing worth practising. Everything else, per Messrs. Graham and Greenblatt, is simply some form of speculation. These are, of course, difficult times, for investors as for everybody else. Given the economic damage wreaked not so much by Covid-19 as by governments’ panicky over-reactions to it, the investment landscape of the future looks like being radically different from the recent past.

The Big State is back, and as a reflection of diminished opportunities, unconscionable debt issuance and weaker growth, bond markets look set for their own Waterloo, whether in the form of a debt jubilee, widespread defaults, a gigantic reset or a particularly messy outbreak of inflation or stagflation. Given that property is in many respects a debt-like asset, not least by its sensitivity to interest rates, and in the light of new attitudes towards working and commuting in a post-Covid world, both residential and commercial property values need to be reassessed by careful investors. So, of the three major asset classes, at least two of them seem to us to be facing significant headwinds. That leaves listed equities, in a world that, at least in the West, seems committed to Net Zero-related economic suicide. And in the context of the monumental money printing fiasco we are now trapped within globally, ‘value’ mining stocks are, in our view, now unparalleled opportunities from a risk / reward perspective (i.e. with relatively limited downside but extreme upside). What type of stocks do you gain comfort from holding in this brave new world ? Ignore reports of their death; value stocks – especially within the commodities sector – are now very much alive.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio – with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

…………

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks.

“An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.”

“All investing is value investing, the rest is speculation.”

Get your Free

financial review

One of the inevitable facets of the investment business is that if you stick around long enough within it, you get to see everything – twice. So it is a reliable rule of thumb that every few years, breathless financial journalists will gleefully report the death of value investing. True to form, ‘The Financial Times’, just a few months into the ‘pandemic’ back in 2020, ran with one of its Big Read op-eds, ‘Does value investing still make sense ?’ The sub-head gives you the gist of the piece:

“The strategy that once worked for Keynes and Buffett has performed badly. The pandemic has compounded the pain.”

“Once” ? To our knowledge Keynes was a speculator who had to be bailed out on multiple occasions. Hunter Lewis for the Mises website corrects the popular view of Keynes as some kind of value investing legend:

“Keynes’s initial foray into investing led to a smash up. He lost everything he had unwisely borrowed and had to be bailed out by his parents, who had some inherited money but were not wealthy.

“He did not do well in the 1920s. He was taken unawares by the 1929 Crash and also by the 1937 rout. In both instances, he came perilously close to being wiped out again because of very concentrated holdings of currencies, stocks, and commodities and continuing use of leverage (as much as one pound of debt for every pound of his own). In short, Keynes was a speculator, at the same time that he criticized speculators and the “casino” atmosphere of the market. He also failed entirely to understand that the casino was fuelled by the easy money policies which he espoused..”

“Once” ? Warren Buffett’s track record at Berkshire Hathaway encompasses a more than half a century period during which shareholders enjoyed an average annual return of roughly 20%, compounding to an overall return of over 4,000,000%. We should all be so lucky to enjoy such “occasional” performance.

An FT reader then weighed in, to put the boot a little more firmly into the stomach of value investing. A John Price (no relation) of Saratoga wrote in to say:

“Reading the FT Big Read (Tuesday May 12) and the role of Benjamin Graham, who defined “value investing” in 1934, readers may not know that Graham in later years became well aware of profound changes in the availability of information and analysis, and its implications.

“In 1976, the year of his death, he wrote: “I am no longer an advocate of elaborate techniques of security analysis in order to find superior value opportunities. This was a rewarding activity when ‘Graham and Dodd’ was first published, but the situation has changed . . . Today I doubt whether such extensive efforts will generate sufficiently superior selections to justify their cost . . . I’m on the side of the Efficient Market school of thought.”

“Today, 46 years after Graham’s death, and despite years of poor returns for value stocks, the advocates of value investing are still “unshakeable in their faith that past patterns will reassert themselves”. To me, it now sounds more like a religion than a rational approach to investing !”

We must confess we were unaware of Ben Graham’s apparent deathbed conversion to the Efficient Market Hypothesis, but we still feel that Mr Price wildly overstates his case. Take those “years of poor returns for value stocks”, for example. Which years would those be, exactly ?

Let’s take the long view, again. Bank of America Merrill Lynch recently crunched the numbers for the US market over a 90 year period (1926-2015) and found that whereas growth stocks delivered average annual returns of 12.6% over the period in question, value stocks returned, on average, 17% by comparison.

Intriguingly, another FT reader, a Mr David Coombs from Corby, Northamptonshire, then weighed in, in rebuttal to Mr Price:

“I consider John Price’s suggestion that Benjamin Graham rejected the strategy of value investment towards the end of his life to be disingenuous (“Keeping faith with value investment makes no sense”, Letters, May 14).

“In the interview to which Mr Price refers, he omits the beginning of the sentence used to make his main point. Graham actually stated: “To that very limited extent I’m on the side of the ‘efficient market’ school of thought.” This changes the context somewhat.

“In the same interview Graham, when asked his recommended approach to investment, states: “The purchase of common stocks at less than their working-capital value.”

In investing, terms like ‘value’ and ‘growth’ are thrown about with abandon, as if everyone had a shared definition. Such a shared definition does not really exist. But here is ours:

A value stock is the listed equity of a company run by principled, shareholder-friendly management with a proven track record of superb asset allocation, where the equity of that company is, for whatever reason, temporarily available at a meaningful discount to its inherent worth.

Index providers tend to maintain certain metrics to distinguish between ‘value’ and ‘growth’ – measures like price to earnings, price to sales, price to book and so forth. These metrics have varying use when it comes to assessing the characteristics of a listed business. Our favourite metrics tend to focus on cash flow, given that cash, unlike earnings, is difficult to manipulate. Cash, in this context, is in fact king. If we were to pick just one metric as a helpful identifier in the cause of value investing, it would be Enterprise Value (the sum of a company’s debt and equity) relative to cashflow from operations. Invert that relationship and you get a measurement of cash flow yield. Beyond that, we simply look to avoid companies in sectors that are too problematic or otherwise expensive – banks being a good example of the former, and many fast-growing technology companies being examples of the latter. Outside these pet biases, we try to be sector-agnostic, because you just never know, and it helps to have the widest opportunity set possible. And as we regularly take pains to point out, it makes sense to avoid companies carrying high levels of debt on their balance sheet, because they simply may not make it through to the other side during environments of acute economic distress.

Value vs Growth (MSCI World Value Index / MSCI World Growth Index, 1975 – 2024)

Source: Bloomberg LLP

Nevertheless, as the chart above shows quite vividly, the relative outperformance of growth versus value (at least in terms of the composition of MSCI’s World Growth and World Value indices) has been spectacular since the ‘fever pitch’ of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. As the chart indicates, on a comparative basis, growth stocks are now even more extremely valued than they were in early 2000 at the height of the dotcom boom – and we know what happened shortly thereafter..

Which is what gives us optimism. See also this blog which reiterates the extraordinary comparative underperformance of value stocks over recent years. But as it points out, anyone with a respect for the longer term cycles of history cannot but be positive:

“We are not into calling bottoms or factor timing. But looking at history, it appears that a golden decade for value investing might be ahead. After reaching the bottom in 1904, value earned 9.99% per year above the risk free rate for the next 9 years, recovering its losses. It then continued to rally for another 7 years, earning 17.8% per year above the risk free rate.”

To bet against value now would be betting against human nature. Value stocks aren’t alone in having their deaths announced on a regular basis by the commentariat. Trend-following or momentum strategies also enjoy comparable periods of being hugely out of favour. This is because human emotions don’t fundamentally change, and so financial markets continually ebb and oscillate between extremes of greed (or euphoria) on one hand, and fear (or pessimism) on the other. For those patient investors looking for superior returns, these extreme cycles are not causes for concern but rather sources of opportunity. It is difficult to outperform the crowd when you are part of it.

When bad things happen to “really good” companies

Source: Kopernik Global Investors, LLC

The table above is a reflection of one of our causes for concern at ‘growth’ companies – that when the tide turns, the selling pressure can become painfully acute. Those ‘tipping point’ moments are not necessarily easy to identify in advance, so our preference is not to be exposed to dangerously overpriced investments in the first place. Capital preservation, for us, always trumps the potential for fast and dramatic gains.

Back in the mid-1970s, the glamour stocks of the day were referred to as the “Nifty Fifty”. Times changed and the nomenclature changed, but the downdraft for the dotcom favourites of the early 2000s was just as severe – and during the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-9, the damage incurred by certain financial sector stocks was almost terminal.

In a recent research piece, ‘Making Plans for Nigel’, Kopernik’s founder, David Iben, draws attention to the opportunities now on offer for investors willing to take a more contrarian stance, especially in relation to the commodities sector. Like us he is an especial fan of gold, but this is more than just a gold story. As he writes,

“Let’s turn our attention to other commodities, which recently have reached generationally attractive prices. Most of them hadn’t been especially interesting since they were pushed skyward by the Chinese-driven bubble of a decade ago. They have become interesting again following their decade long decline, in absolute terms and relative to gold, followed by the recent virus-driven coup de grace.. This all paints a picture demonstrating that gold is very cheap compared to the dollar, and other fiat currencies, gold miners are very attractive relative to gold itself, many commodity prices have become very depressed in relation to gold, and commodity related companies have become quite attractive relative to the commodities they own.”

Uranium looks particularly interesting, not least given the trend towards renewables and alternative energy. As Iben observes,

“We don’t typically invest with a “catalyst in mind,” believing that attractive valuation eventually serves as its own catalyst, and having noticed that stocks usually rocket higher before people notice the catalysts. Uranium seems to be one of the rare exceptions. Catalysts have become abundant in recent months. Cameco Corp. closed MacArthur River (maybe the best mine ever). The U.S. Department of Energy stopped selling their stash, and the Russians stopped several years prior. The Kazakhs cut production once, then twice, and just announced a coronavirus related major reduction of supply. Similarly, Cameco closed its Cigar Lake mine, temporarily, due to the coronavirus. Two high-cost mines in Africa have finally closed. On the demand side, demand for electricity is down some, but Japan has reopened nine reactors and China has opened a similar number, with thirty more in various stages of planning and construction. Funds have been formed to buy and hold. Supply falls well short of demand.. Prices need to double, if not triple, to avoid shortages and multi-billion dollar reactors sitting idle.”

But as things stand, both on valuation grounds and because of the sheer scale of governmental reflationary stimulus around the world, and more recently the extent of central bank purchases (in the Ukraine-related aftermath of the freezing of Russia’s foreign reserves), gold remains our single favourite investment. In our worldview at present, all roads lead to gold. And not just gold. Our friend, the investment strategist James Ferguson, recently wrote:

“The Fed’s aggressively huge QE has been equivalent, in just 6-8 weeks, to more than half of what was done over 6 years during resolution. This time, all money measures from narrow to broad are rising steeply; broad money at a record peacetime rate.

“Bank lending is still growing too and the Fed’s $2.3 trillion loan stimulus programme has yet to begin.

“There is even evidence the Fed has been funding the Treasury directly (i.e. MMT), despite MMT having no workable policy to rein back inflation once unleashed.

“We know from past QE which assets benefit (risk-on, precious metals) and which lose out (diluted currencies, bonds). Whilst the bond market may be mesmerized by the output gap, it appears overly complacent about the magnitude and breadth of the policy intervention.

“Gold, unsurprisingly, has already advanced to the cusp of a new all-time, record high but its leveraged acolyte, silver, is obligingly at a record relative discount, so at least inflation protection is cheap.”

In other words, for portfolio insurance, portfolio diversification and currency protection, don’t limit yourself to gold.

For many years now we have lived happily with the conclusion that value investing – on our terms, at least – is the only form of investing worth practising. Everything else, per Messrs. Graham and Greenblatt, is simply some form of speculation. These are, of course, difficult times, for investors as for everybody else. Given the economic damage wreaked not so much by Covid-19 as by governments’ panicky over-reactions to it, the investment landscape of the future looks like being radically different from the recent past.

The Big State is back, and as a reflection of diminished opportunities, unconscionable debt issuance and weaker growth, bond markets look set for their own Waterloo, whether in the form of a debt jubilee, widespread defaults, a gigantic reset or a particularly messy outbreak of inflation or stagflation. Given that property is in many respects a debt-like asset, not least by its sensitivity to interest rates, and in the light of new attitudes towards working and commuting in a post-Covid world, both residential and commercial property values need to be reassessed by careful investors. So, of the three major asset classes, at least two of them seem to us to be facing significant headwinds. That leaves listed equities, in a world that, at least in the West, seems committed to Net Zero-related economic suicide. And in the context of the monumental money printing fiasco we are now trapped within globally, ‘value’ mining stocks are, in our view, now unparalleled opportunities from a risk / reward perspective (i.e. with relatively limited downside but extreme upside). What type of stocks do you gain comfort from holding in this brave new world ? Ignore reports of their death; value stocks – especially within the commodities sector – are now very much alive.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio – with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

…………

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price