According to the late, great Canadian value investor, Peter Cundill, “there’s always something to do”. What he meant, we suspect, was that regardless of apparent overvaluations in certain markets, there are always undiscovered bargains somewhere else in this world just waiting to be discovered. (We agree.)

Right now, it seems that there is always something to worry about. A list that includes the global debt mountain, central bank policy paralysis over interest rates and a general mistrust of (crony) capitalism, has now been joined by the economic aftermath (?) of the coronavirus crisis and the possibility of a hot war on the Russia / Ukraine border.

To all of which there is an obvious response. Given that deposit rates are derisory, the pragmatic conclusion has to be to invest defensively and in a genuinely diversified way. Inasmuch as listed equities are likely to form the lion’s share of even the most defensively minded investors’ portfolios – let’s not dwell on the risks of bonds for the moment – how do we retain skin in the game without exposing our capital to overmuch risk ?

Our answer, not just now but for all time, is value investing, practised according to the time-honoured principles of Benjamin Graham, author of the value investor’s Bible, The Intelligent Investor. If the name Ben Graham is unfamiliar to you, bear in mind he’s the person who taught Warren Buffett at Columbia Business School. Enough said, perhaps.

In his introduction to a re-issue of Ben Graham’s book, the Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Zweig writes that

“..this book will teach you three powerful lessons: how you can minimize the odds of suffering irreversible losses; how you can maximize the chances of achieving sustainable gains; how you can control the self-defeating behaviour that keeps most investors from reaching their full potential.”

Graham handled the first two objectives with his concept of the ‘margin of safety’. Equity investors can secure a ‘margin of safety’ when they purchase securities at a price sufficiently below the business’ underlying value to allow for human error, bad luck or – something else.

Within our own investment business, we pursue Ben Graham’s vision of investing by trying to focus solely on the shares of companies run by principled, shareholder-friendly management with an absolute mastery of capital allocation when and only when we can buy such securities at a meaningful discount to their inherent worth. Any assessment of corporate talent is bound to be at least somewhat subjective, but happily there are some objective measures of value that can be assessed mathematically. They include, for example, the following metrics:

- At least a 10% cashflow from operations yield (the cashflow from a company’s operations divided by the combined value of the company’s equity and debt)

- A price / earnings ratio of, ideally, less than 15 times

- A price / book ratio of less than 1.5 times and ideally less than 1x

- A debt / total assets ratio of, ideally, less than 30%

- Cash from operations growth (we have no interest in declining or stagnating businesses)

- A return on equity of at least 8% on average per annum.

Fulfilling these criteria is no guarantee, of course, of securing a successful investment, but they’re unlikely to hurt your prospects of such, especially if you can identify genuinely able management.

And then there’s the market experience of the last 10 years..

Conventional wisdom has it that value stocks have been a disaster for the last decade – ever since central bank monetary policy drifted away from any form of rationality and became the biggest experiment in world monetary history. The reality is more down-to-earth. To outperform over the last 10 years, you needed to do just two things. One: own the US stock market and forget all the others. Two: ignore almost all of the US stock market and concentrate on the shares of Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google and Microsoft. Those FAANGM stocks, for example, between 2015 and the end of 2019 delivered returns of 300%. The S&P 500 index itself over the same period delivered a return of 72%.

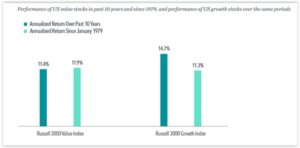

As the asset managers at the US firm Dimensional Fund Advisors point out, the recent returns from value stocks – in the US market, at least – have been broadly in line with their long run average. As their charts below show, the annualised return of US value stocks for the last decade stands at 11.4%, just a shade below their overall annualised return since January 1979.

The real outlier is growth. US growth stocks for the last 10 years delivered investors lucky or shrewd enough to own them 14.7% on average, annualised, versus a return of 11.3% for the period since January 1979.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP.

(If you’re interested in seeing DFA’s original piece, you can find it here.)

So, at least for US investors, value has not been a recent disaster. Rather, growth has been an almost incredible triumph.

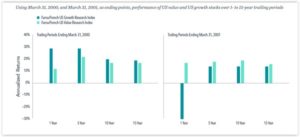

Their research doesn’t end there. Have there been previous examples of the market suddenly flipping back from a preference for growth to one of value ? Indeed there have. It was called the first dotcom boom. Consider the charts below.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP.

As DFA are quick to point out,

“While stock returns are unpredictable, there is precedent for the value premium turning around quickly after periods of sustained underperformance. For example, some of the weakest periods for value stocks when compared to growth stocks have been followed by some of the strongest.. On March 31, 2000, growth stocks had outperformed value stocks in the US over the prior year, prior five years, prior 10 years, and prior 15 years. As of March 31, 2001—one year and one market swing later—value stocks had regained the advantage over every one of those periods.”

Sentiment, in other words, can change on a dime. In the process, it can swiftly reverse 10 years of accumulated outperformance.

As DFA go on to say,

“The theoretical support for value investing is longstanding—paying a lower price means a higher expected return. However, realized returns are volatile. A 10-year negative premium, while not expected, is not unusual.

“But history also tells us that changing course after a disappointing spell for known premiums can lead to missed opportunities. When those drivers of outperformance have turned around in the past, steadfast investors have been rewarded. A key to successful long-term investing is sticking with your approach, even through difficult periods, so that you are there for the good times too.”

Peter Cundill also famously wrote that

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. The majority of investors do not possess this characteristic.”

Readers of a certain vintage may remember Fidelity’s star manager Peter Lynch, who steered its Magellan Fund between 1977 and 1990. During that period Lynch’s average annual return to investors was 29%. How much do we think the fund’s average investor made over the same period ? Michael Torrence of Alpha Wealth Funds suggests that the average investor in Peter Lynch’s fund lost money over the same period. If this seems extraordinary – and it surely is – it is a reflection of the average individual investor’s propensity to take profits too quickly and to sell out despondently too quickly, too.

Ben Graham had a way of describing this sort of behaviour. He even coined the phrase ‘Mister Market’ to define it. Jason Zweig picks up the story. Sometimes, the price is not right. Sometimes, the price is very wrong indeed.

“..at such times, you need to understand Graham’s image of Mr. Market, probably the most brilliant metaphor ever created for explaining how stocks can become mispriced. The manic-depressive Mr. Market does not always price stocks the way an appraiser or a private buyer would value a business. Instead, when stocks are going up, he happily pays more than their objective value; and, when they are going down, he is desperate to dump them for less than their true worth..”

There is nothing wrong with ‘momentum’ investing (trading, to be fair, would be a better description), but we should recognise it for what it is worth, and it is not value investing. It is not even investing by Ben Graham’s earlier definition. Rather, it is speculation – that what has gone up will continue to go up. We allocate to systematic trend-following funds, not least given their lack of historic correlation to stocks and bonds, but only to those with a strong and proven pedigree of prudent risk management.

We generally prefer a far more defensive stance than most of our competitors, not least because we sense storm clouds ahead. As Ben Graham rightly observed, you can invest on the basis of hope, or you can invest on the basis of mathematics. In this instance, we prefer mathematics.

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

According to the late, great Canadian value investor, Peter Cundill, “there’s always something to do”. What he meant, we suspect, was that regardless of apparent overvaluations in certain markets, there are always undiscovered bargains somewhere else in this world just waiting to be discovered. (We agree.)

Right now, it seems that there is always something to worry about. A list that includes the global debt mountain, central bank policy paralysis over interest rates and a general mistrust of (crony) capitalism, has now been joined by the economic aftermath (?) of the coronavirus crisis and the possibility of a hot war on the Russia / Ukraine border.

To all of which there is an obvious response. Given that deposit rates are derisory, the pragmatic conclusion has to be to invest defensively and in a genuinely diversified way. Inasmuch as listed equities are likely to form the lion’s share of even the most defensively minded investors’ portfolios – let’s not dwell on the risks of bonds for the moment – how do we retain skin in the game without exposing our capital to overmuch risk ?

Our answer, not just now but for all time, is value investing, practised according to the time-honoured principles of Benjamin Graham, author of the value investor’s Bible, The Intelligent Investor. If the name Ben Graham is unfamiliar to you, bear in mind he’s the person who taught Warren Buffett at Columbia Business School. Enough said, perhaps.

In his introduction to a re-issue of Ben Graham’s book, the Wall Street Journal columnist Jason Zweig writes that

“..this book will teach you three powerful lessons: how you can minimize the odds of suffering irreversible losses; how you can maximize the chances of achieving sustainable gains; how you can control the self-defeating behaviour that keeps most investors from reaching their full potential.”

Graham handled the first two objectives with his concept of the ‘margin of safety’. Equity investors can secure a ‘margin of safety’ when they purchase securities at a price sufficiently below the business’ underlying value to allow for human error, bad luck or – something else.

Within our own investment business, we pursue Ben Graham’s vision of investing by trying to focus solely on the shares of companies run by principled, shareholder-friendly management with an absolute mastery of capital allocation when and only when we can buy such securities at a meaningful discount to their inherent worth. Any assessment of corporate talent is bound to be at least somewhat subjective, but happily there are some objective measures of value that can be assessed mathematically. They include, for example, the following metrics:

Fulfilling these criteria is no guarantee, of course, of securing a successful investment, but they’re unlikely to hurt your prospects of such, especially if you can identify genuinely able management.

And then there’s the market experience of the last 10 years..

Conventional wisdom has it that value stocks have been a disaster for the last decade – ever since central bank monetary policy drifted away from any form of rationality and became the biggest experiment in world monetary history. The reality is more down-to-earth. To outperform over the last 10 years, you needed to do just two things. One: own the US stock market and forget all the others. Two: ignore almost all of the US stock market and concentrate on the shares of Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google and Microsoft. Those FAANGM stocks, for example, between 2015 and the end of 2019 delivered returns of 300%. The S&P 500 index itself over the same period delivered a return of 72%.

As the asset managers at the US firm Dimensional Fund Advisors point out, the recent returns from value stocks – in the US market, at least – have been broadly in line with their long run average. As their charts below show, the annualised return of US value stocks for the last decade stands at 11.4%, just a shade below their overall annualised return since January 1979.

The real outlier is growth. US growth stocks for the last 10 years delivered investors lucky or shrewd enough to own them 14.7% on average, annualised, versus a return of 11.3% for the period since January 1979.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP.

(If you’re interested in seeing DFA’s original piece, you can find it here.)

So, at least for US investors, value has not been a recent disaster. Rather, growth has been an almost incredible triumph.

Their research doesn’t end there. Have there been previous examples of the market suddenly flipping back from a preference for growth to one of value ? Indeed there have. It was called the first dotcom boom. Consider the charts below.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP.

As DFA are quick to point out,

“While stock returns are unpredictable, there is precedent for the value premium turning around quickly after periods of sustained underperformance. For example, some of the weakest periods for value stocks when compared to growth stocks have been followed by some of the strongest.. On March 31, 2000, growth stocks had outperformed value stocks in the US over the prior year, prior five years, prior 10 years, and prior 15 years. As of March 31, 2001—one year and one market swing later—value stocks had regained the advantage over every one of those periods.”

Sentiment, in other words, can change on a dime. In the process, it can swiftly reverse 10 years of accumulated outperformance.

As DFA go on to say,

“The theoretical support for value investing is longstanding—paying a lower price means a higher expected return. However, realized returns are volatile. A 10-year negative premium, while not expected, is not unusual.

“But history also tells us that changing course after a disappointing spell for known premiums can lead to missed opportunities. When those drivers of outperformance have turned around in the past, steadfast investors have been rewarded. A key to successful long-term investing is sticking with your approach, even through difficult periods, so that you are there for the good times too.”

Peter Cundill also famously wrote that

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. The majority of investors do not possess this characteristic.”

Readers of a certain vintage may remember Fidelity’s star manager Peter Lynch, who steered its Magellan Fund between 1977 and 1990. During that period Lynch’s average annual return to investors was 29%. How much do we think the fund’s average investor made over the same period ? Michael Torrence of Alpha Wealth Funds suggests that the average investor in Peter Lynch’s fund lost money over the same period. If this seems extraordinary – and it surely is – it is a reflection of the average individual investor’s propensity to take profits too quickly and to sell out despondently too quickly, too.

Ben Graham had a way of describing this sort of behaviour. He even coined the phrase ‘Mister Market’ to define it. Jason Zweig picks up the story. Sometimes, the price is not right. Sometimes, the price is very wrong indeed.

“..at such times, you need to understand Graham’s image of Mr. Market, probably the most brilliant metaphor ever created for explaining how stocks can become mispriced. The manic-depressive Mr. Market does not always price stocks the way an appraiser or a private buyer would value a business. Instead, when stocks are going up, he happily pays more than their objective value; and, when they are going down, he is desperate to dump them for less than their true worth..”

There is nothing wrong with ‘momentum’ investing (trading, to be fair, would be a better description), but we should recognise it for what it is worth, and it is not value investing. It is not even investing by Ben Graham’s earlier definition. Rather, it is speculation – that what has gone up will continue to go up. We allocate to systematic trend-following funds, not least given their lack of historic correlation to stocks and bonds, but only to those with a strong and proven pedigree of prudent risk management.

We generally prefer a far more defensive stance than most of our competitors, not least because we sense storm clouds ahead. As Ben Graham rightly observed, you can invest on the basis of hope, or you can invest on the basis of mathematics. In this instance, we prefer mathematics.

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price