On Thursday 9 April 1992 the United Kingdom held a general election. The country was in recession. We recall this vividly because, having graduated with an English degree the previous summer, this correspondent hadn’t managed to secure any type of job in the field that he wanted to work – journalism (lucky escape) – so he had to settle for what he could get, which in this case was an entry level job as a bond salesman with a third tier Japanese bank.

For weeks, the left-leaning Labour Party had been ahead in the pre-election polls. The Conservatives were on the ropes. One of the country’s greatest ever Prime Ministers, Margaret Thatcher, had recently been ousted by Conservative Europhiles after a very public row about the UK’s future in Europe. Under the leadership of the socialist firebrand Neil Kinnock, Labour was finally electable. All the opinion polls pointed to a Labour victory.

And the opinion polls felt wrong.

So on that April afternoon, a cry went up in the dealing room this correspondent worked in. A bunch of traders were “buying” Conservative seats in a pre-election wager through a spread betting firm. (With the polls pointing to a Labour win, the number of forecast Conservative seats in Parliament seemed artificially low.) They asked if we wanted to join the bet. We happily agreed; we felt the polls were wrong too, and they didn’t reflect the national mood. “Put me down for £5.”

As this was our first spread bet, we thought we were in for a discrete wager of £5. Knowing very little about anything at the time, we didn’t realise we were in for £5 per seat.

There are 650 seats in the British Parliament. In the admittedly unrealistic but worst case scenario of the Conservatives being completely wiped out in the election, we stood to lose several thousand pounds.

Lesson Number One: before you put capital at risk in the market, do some research. At the very minimum, have at least some kind of clue what you are doing.

It all ended happily (both for the country, and for us). On a monstrous election turnout of almost 80 percent of the electorate, the Conservatives were re-elected with a majority of 21 seats. We made a lot of money from our little bet. Our genius was confirmed.

Fast forward, then, to Thursday 8 June 2017.

UK Prime Minister, the Conservative leader Theresa May, has called a snap election to strengthen her hand in looming Brexit negotiations. Yes, the British political establishment, 25 years later, is still tearing itself apart over Europe.

The pre-election polls all indicate a surge in support for Labour, under its socialist firebrand leader Jeremy Corbyn. You can guess where this anecdote is headed..

So we think history is going to repeat itself. For only the second time in history, we make a political bet. We think the 1992 experience is going to repeat itself verbatim. Labour’s lead in the polls is overstated. Conservative seats are clearly mispriced. We “buy” Conservative seats through a spread betting platform.

My brother invites me over to his home in St John’s Wood to watch on TV as the election results come in. He has “bought” Conservative seats too. The polls all feel wrong.

At 9.50 p.m. on Thursday 8 June, David Dimbleby begins hosting the live election coverage from the BBC. It is unlawful to report even the results of unofficial exit polls at a general election in the UK until the polling booths close across the country at 10 p.m. But Dimbleby, along with a handful of graphic designers at the BBC, knows the results of the BBC’s exit polls because he has to report on them to millions of people in 10 minutes’ time.

He looks ashen-faced. Shocked, even. An injudicious tweet from a pollster and political forecaster at 9.30 p.m. has already indicated that commentators will be discussing the “fascinating” outcome of the election for years to come.

We suddenly realise that we have made a dreadful mistake.

At 10 p.m. ‘purdah’ is lifted and David Dimbleby delivers the verdict of the BBC’s exit poll:

It will be a hung Parliament, with no political party enjoying an overall majority.

The BBC’s exit poll turns out to be stunningly accurate. They forecast 314 seats for the Conservatives, 266 for Labour, and 34 for the Scottish National Party. (No other party has a meaningful share of the vote.)

The actual result ? 314 seats for the Conservatives, 266 for Labour, and 34 for the Scottish National Party. The BBC exit poll nailed it.

To get a sense of just how badly we called this one, we had gone “long” Conservative seats at 360, which seemed a fair price when we first placed the bet. We ended up being offside by nearly 50 seats.

Lesson Number Two: if you’re going to speculate, only risk what you can comfortably afford to lose. For this correspondent, this was just a playful speculation, and as such there wasn’t much at stake. But that doesn’t detract at all from the core observation that you should treat seemingly casual bets just as seriously as any others.

Lesson Number Three: wherever you can, employ a ‘stop loss’. We knew in advance what our downside was, because we put in a ‘stop loss’ order before we made the bet. Our own position was stopped out, mechanically, at 320 seats, as the Conservative lead in the final poll evaporated. Which gave us a tiny crumb of comfort during our feast of pain.

And Lesson Number Four, the most important of all of them: if you don’t know what your edge is, you do not have one.

When it came to betting on the outcome of that year’s general election, we had no superior knowledge of the political situation. We had no proprietary insight into people’s voting intentions. We had no ‘edge’. This correspondent allowed himself to be swayed by his gut, and by a sentimental recollection of a previous situation that, from a purely superficial analysis, seemed to be very similar. We allowed our heart to overrule our head.

But it does lead us to wonder what the state of mind is for the average investor when they make a typical investment. Are they putting money in jeopardy on the basis of any rational assessment of the situation – or are they gambling on the basis of nothing more than a gut feeling ?

Warren Buffett once remarked:

“I will tell you how to become rich. Close the doors. Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful.”

It’s a casual aside. Being contrarian as an investor may be necessary, but it is certainly insufficient. There is one crucial factor missing from this advice. It also happens to be the most important characteristic of any investment you will ever make, whether in stocks, bonds, property, private equity, or anything else.

This factor is price.

It is also the factor that, in a hideous irony, has virtually disappeared from any popular coverage of the financial markets by the mainstream investment media. For many supposed investors today, “investing” amounts to anticipating market direction – to forecasting capital flows, in other words. As in Keynes’ famous beauty contest analogy, they’re not voting for the prettiest girl, but rather the girl they think the other judges might find prettiest in the future. This sort of “investing” isn’t gathering a rich harvest from the psychological biases of others (which is what value investing amounts to, by scooping up the bargains that the mob wilfully overlooks) but is simply speculating about how those biases might change. But that isn’t investing at all, it’s highly speculative fortune-telling. Value investing doesn’t need to be about forecasting anything. It’s about identifying obvious value today and then just waiting for the magic of mean reversion to do its thing. Value investing begins and ends with the price on offer. If it’s a quality business, a cheap price is a good one.

Oaktree Capital’s Howard Marks, one of the all-time great investors, states that

“For a value investor, price has to be the starting point. It has been demonstrated time and time again that no asset is so good that it can’t become a bad investment if bought at too high a price. And there are few assets so bad that they can’t be a good investment when bought cheap enough.”

In other words, there are no bad assets – just bad prices. The key determinant between your investment success and investment failure is the price you elect to pay for what you own. And we use the word ‘elect’ advisedly – nobody ever forces you to buy anything, at any price. The market always offers you a choice.

Price is everything and price is in many respects the only thing that matters. Everything else is secondary.

It has taken this correspondent a quarter of a century of working in the capital markets to learn this lesson.

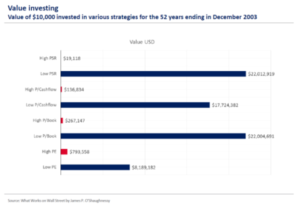

Whenever we pitch our value fund to prospective investors, we always include the following chart. It is taken from James O’Shaughnessy’s ‘What works on Wall Street’ (McGraw-Hill 2011). It is perhaps the definitive proof of the long term success of value investing.

O’Shaughnessy screened the entire US stock market by valuation. He selected the 50 highest rated stocks on the basis of price to sales ratio (High PSR) and then the 50 lowest rated stocks on the same basis. He did the same for price to cashflow, price to book and price to earnings (PE). He then rolled the clock forward for half a century and annually rebalanced these lists so that they continually comprised the 50 most expensive stocks and the 50 cheapest stocks by each metric. The results are shown below.

Take price / book – the share price of a company by comparison to its underlying inherent (or book) value per share.

If you started out with the 50 most expensive US stocks on a price / book basis, and then continually rebalanced that list of 50 stocks so that you always owned the most expensive 50 stocks, a portfolio with a starting value of $10,000 would, after 52 years, be worth $267,147.

Which sounds great, or at least okay, until you see what you could have made by owning the cheapest stocks instead.

If you had held the 50 cheapest stocks as expressed by their price / book ratio, and continually rebalanced that portfolio every year so that you stayed with the 50 cheapest stocks, your portfolio of $10,000 would, after 52 years, be worth $22,004,691.

If you come across a more compelling display of the merits of value investing, please let us know, because we happen to doubt whether such evidence exists. This is dynamite stuff.

From O’Shaughnessy himself:

“When you look back as far as 80 years for which we have data, rather than moving about without rhyme or reason, the stock market methodically rewards certain investment strategies while punishing others. There’s no question the value-based strategies that work over long periods of time don’t work all the time, but history shows that after what turn out to be relatively brief periods when other things seem to be all that matter, the market reasserts its preference for value, often with ferocity. My basic premise is that given all that, investors can do much better than the market if they consistently use time-tested strategies that are based on sensible, rational, value-based methods for selecting stocks.”

Lest you think we’re being partial, here’s another study.

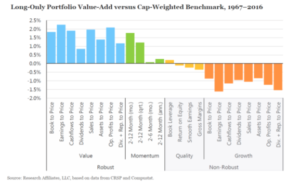

Fund managers Research Affiliates recently published a study entitled ‘How not to get fired with smart beta investing’.

They crunched the numbers for 50 years, and found that certain investment strategies added value versus a market capitalisation weighted benchmark (such as the S&P 500 index), and other strategies destroyed value versus a market cap-weighted benchmark.

Research Affiliates split the market up into four ‘styles’: value (i.e. cheap companies); momentum (companies whose share prices are rising sharply in price); quality (i.e. relatively resilient and economically enduring companies in sectors like pharmaceuticals) and finally growth (i.e. expensive companies, such as today’s so-called FANGs – the likes of Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google).

What they found was intriguing, and extremely useful for investors looking for an edge.

Two styles added value consistently (Research Affiliates described them as ‘Robust’) – generating additional value of between fractions of a percent and over 2 percent annually, versus the benchmark. Those styles were value, and then momentum. We would indeed go further: we happen to think that value and momentum are, between them, the only ways of sustainably making money from the stock market over the medium term. Value is clearly our favourite, but we acknowledge that momentum can also work, which is why we also use systematic trend-following funds as part of our investible universe.

Two percent added value per annum may not seem like much, but over time it compounds wonderfully, as James O’Shaughnessy’s table shows.

Two styles, on the other hand, destroyed value versus the benchmark (Research Affiliates described them as ‘Non-Robust’; we would have used less charitable language). One of them was ‘quality’ – in essence, overpaying for companies, and the other was ‘growth’ – again, effectively, overpaying for (temporarily) high earnings, or at least the potential for high earnings in the future.

Given that both O’Shaughnessy’s and Research Affiliates’ studies comprised over 50 years’ worth of returns, we think we can take them seriously. These are statistically meaningful periods of time.

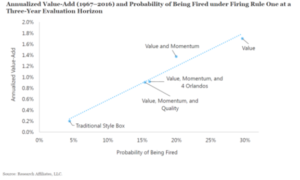

Research Affiliates than go on to make an additional point which is truly incredible. Although they show that value investing is clearly the single most successful investment strategy over the medium to longer term, they also point out that value investing is at the same time the investment strategy that is most likely to get a financial adviser fired by his client for recommending it. Their study, again using annualized value added, is shown below.

(The reference to 4 Orlandos, if you’re interested, shows the results of a random portfolio of stocks selected by Orlando, the stock-picking cat.)

If this study doesn’t prove that investors are irrational, nothing will. The reason that investors will tend to fire value managers is that they don’t have the stamina to accept sub-par performance in the short run. The irony, of course, is that no strategy on this planet works consistently, year in, year out – but value comes closest to that objective over the medium term. But the average investor, living in the moment, doesn’t have the patience to see it through.

When we first came across the O’Shaughnessy study, we nearly fell off our chair. When we came across the Research Affiliates study, we nearly fell off the floor.

At the risk of labouring the point, price is pretty much the only thing that matters. In terms of the listed equity markets, try and identify high quality businesses, with principled, shareholder-friendly management, and then try and buy them when their shares are available at close to or, ideally, below their inherent value, or book value. This is the investment methodology that drives every investment we make. And because the US stock market happens to be abnormally expensive, it makes perfect sense to cast one’s net as widely as possible internationally, because nobody is forcing us to indulge in home country bias. If the value happens to be in Asia (which it largely does, in our view, today), then start hunting for value opportunities there. Caveat: per Research Affiliates’ second observation, be prepared to wait. Value investing does not offer instant gratification. The great Canadian value investor Peter Cundill was spot on when he said,

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. THE MAJORITY OF INVESTORS DO NOT POSSESS THIS CHARACTERISTIC.”

Focus on price, and then try and be patient.

But human beings are suckers for stories. Our lives are driven by narratives. In the words of the X-Files, we want to believe. Anything to do with valuation gets thrown under the bus as being irrelevant. The story is more compelling than the price.

We suggest that the average investor is motivated more strongly by stories – by hope, if you like – than by anything else. And Wall Street, CNBC and our investment media en masse are more than happy to keep fuelling this fire. Narratives engage our emotions more than any amount of rational analysis. The great insight of the classical economists is that economic interaction takes place between human beings with a tendency towards the irrational. All of modern portfolio theory derives from a false premise, that markets are efficient. Well, they will be when we are. And that is going to be: never. Value investing amounts to a process whereby rational and patient investors take money away from irrational, impatient and credulous ones.

The beginning of the end ?

Our strong suspicion is that we are very close to the tail end of a monumental rally that has taken developed world stock and bond markets, including but not limited to those of the US, to dangerously unsustainable levels. This view is shared by strategist David Murrin.

Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted p/e (or CAPE) for the S&P 500 stock index is now – at over 29 times and despite the recent correction – essentially at the same level as on Black Tuesday 1929. Its long run average is less than 17 times.

Robert Shiller CAPE ratio, 1880 – 2022

Source: http://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe/

So to anyone who believes in long term reversion to the mean, US stocks remain heavily overvalued.

The so-called FANGs (the likes of Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google) have been dominant drivers of recent stock market gains. Their popularity is akin to that of the so-called Nifty Fifty of the early 1970s – just before they cratered.

Perhaps most ominously, the Fed is in the early stages of normalising US interest rates. We are now in the earliest phase of Quantitative Tightening. And there is an iron clad relationship between interest rates and bond prices. If interest rates go up, bond prices go down.

What could possibly go wrong ?

Clearly, plenty of things could.

But don’t confuse this for a counsel of despair. The beauty of value investing is that if we’ve done our homework well enough, any market decline makes our favoured securities even better value; what Benjamin Graham calls their “margin of safety” gets even bigger. This is intuitively obvious, given that we are trying to find dollar bills for 40 cents. If those dollar bills suddenly trade at 30 cents, are they more or less attractive than they were at 40 ? In the immortal words of fund manager Cullen Roche,

“The stock market is the only market where things go on sale and all the customers run out of the store.”

It makes sense to panic if the price of your overpriced growth-at-any-cost stocks starts to weaken. Since all those stocks had going for them in the first place was momentum, if the momentum of the market starts to turn, you probably should be running for the exit.

But at a time when the prices of so many financial assets – stocks, bonds, property – are juiced by trillions of dollars’ worth of free money and QE, genuinely defensive value investments from around the world, selected on an entirely unconstrained basis, are about the only public market investments worth making.

Last word this week goes to Howard Marks:

“If I had to identify a single key to consistently successful investing, I’d say it’s “cheapness”. Buying at low prices relative to intrinsic value (rigorously and conservatively derived) holds the key to earning dependably high returns, limiting risk and minimizing losses. It’s not the only thing that matters – obviously – but it’s something for which there is no substitute.”

Go forth and prosper !

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

On Thursday 9 April 1992 the United Kingdom held a general election. The country was in recession. We recall this vividly because, having graduated with an English degree the previous summer, this correspondent hadn’t managed to secure any type of job in the field that he wanted to work – journalism (lucky escape) – so he had to settle for what he could get, which in this case was an entry level job as a bond salesman with a third tier Japanese bank.

For weeks, the left-leaning Labour Party had been ahead in the pre-election polls. The Conservatives were on the ropes. One of the country’s greatest ever Prime Ministers, Margaret Thatcher, had recently been ousted by Conservative Europhiles after a very public row about the UK’s future in Europe. Under the leadership of the socialist firebrand Neil Kinnock, Labour was finally electable. All the opinion polls pointed to a Labour victory.

And the opinion polls felt wrong.

So on that April afternoon, a cry went up in the dealing room this correspondent worked in. A bunch of traders were “buying” Conservative seats in a pre-election wager through a spread betting firm. (With the polls pointing to a Labour win, the number of forecast Conservative seats in Parliament seemed artificially low.) They asked if we wanted to join the bet. We happily agreed; we felt the polls were wrong too, and they didn’t reflect the national mood. “Put me down for £5.”

As this was our first spread bet, we thought we were in for a discrete wager of £5. Knowing very little about anything at the time, we didn’t realise we were in for £5 per seat.

There are 650 seats in the British Parliament. In the admittedly unrealistic but worst case scenario of the Conservatives being completely wiped out in the election, we stood to lose several thousand pounds.

Lesson Number One: before you put capital at risk in the market, do some research. At the very minimum, have at least some kind of clue what you are doing.

It all ended happily (both for the country, and for us). On a monstrous election turnout of almost 80 percent of the electorate, the Conservatives were re-elected with a majority of 21 seats. We made a lot of money from our little bet. Our genius was confirmed.

Fast forward, then, to Thursday 8 June 2017.

UK Prime Minister, the Conservative leader Theresa May, has called a snap election to strengthen her hand in looming Brexit negotiations. Yes, the British political establishment, 25 years later, is still tearing itself apart over Europe.

The pre-election polls all indicate a surge in support for Labour, under its socialist firebrand leader Jeremy Corbyn. You can guess where this anecdote is headed..

So we think history is going to repeat itself. For only the second time in history, we make a political bet. We think the 1992 experience is going to repeat itself verbatim. Labour’s lead in the polls is overstated. Conservative seats are clearly mispriced. We “buy” Conservative seats through a spread betting platform.

My brother invites me over to his home in St John’s Wood to watch on TV as the election results come in. He has “bought” Conservative seats too. The polls all feel wrong.

At 9.50 p.m. on Thursday 8 June, David Dimbleby begins hosting the live election coverage from the BBC. It is unlawful to report even the results of unofficial exit polls at a general election in the UK until the polling booths close across the country at 10 p.m. But Dimbleby, along with a handful of graphic designers at the BBC, knows the results of the BBC’s exit polls because he has to report on them to millions of people in 10 minutes’ time.

He looks ashen-faced. Shocked, even. An injudicious tweet from a pollster and political forecaster at 9.30 p.m. has already indicated that commentators will be discussing the “fascinating” outcome of the election for years to come.

We suddenly realise that we have made a dreadful mistake.

At 10 p.m. ‘purdah’ is lifted and David Dimbleby delivers the verdict of the BBC’s exit poll:

It will be a hung Parliament, with no political party enjoying an overall majority.

The BBC’s exit poll turns out to be stunningly accurate. They forecast 314 seats for the Conservatives, 266 for Labour, and 34 for the Scottish National Party. (No other party has a meaningful share of the vote.)

The actual result ? 314 seats for the Conservatives, 266 for Labour, and 34 for the Scottish National Party. The BBC exit poll nailed it.

To get a sense of just how badly we called this one, we had gone “long” Conservative seats at 360, which seemed a fair price when we first placed the bet. We ended up being offside by nearly 50 seats.

Lesson Number Two: if you’re going to speculate, only risk what you can comfortably afford to lose. For this correspondent, this was just a playful speculation, and as such there wasn’t much at stake. But that doesn’t detract at all from the core observation that you should treat seemingly casual bets just as seriously as any others.

Lesson Number Three: wherever you can, employ a ‘stop loss’. We knew in advance what our downside was, because we put in a ‘stop loss’ order before we made the bet. Our own position was stopped out, mechanically, at 320 seats, as the Conservative lead in the final poll evaporated. Which gave us a tiny crumb of comfort during our feast of pain.

And Lesson Number Four, the most important of all of them: if you don’t know what your edge is, you do not have one.

When it came to betting on the outcome of that year’s general election, we had no superior knowledge of the political situation. We had no proprietary insight into people’s voting intentions. We had no ‘edge’. This correspondent allowed himself to be swayed by his gut, and by a sentimental recollection of a previous situation that, from a purely superficial analysis, seemed to be very similar. We allowed our heart to overrule our head.

But it does lead us to wonder what the state of mind is for the average investor when they make a typical investment. Are they putting money in jeopardy on the basis of any rational assessment of the situation – or are they gambling on the basis of nothing more than a gut feeling ?

Warren Buffett once remarked:

“I will tell you how to become rich. Close the doors. Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful.”

It’s a casual aside. Being contrarian as an investor may be necessary, but it is certainly insufficient. There is one crucial factor missing from this advice. It also happens to be the most important characteristic of any investment you will ever make, whether in stocks, bonds, property, private equity, or anything else.

This factor is price.

It is also the factor that, in a hideous irony, has virtually disappeared from any popular coverage of the financial markets by the mainstream investment media. For many supposed investors today, “investing” amounts to anticipating market direction – to forecasting capital flows, in other words. As in Keynes’ famous beauty contest analogy, they’re not voting for the prettiest girl, but rather the girl they think the other judges might find prettiest in the future. This sort of “investing” isn’t gathering a rich harvest from the psychological biases of others (which is what value investing amounts to, by scooping up the bargains that the mob wilfully overlooks) but is simply speculating about how those biases might change. But that isn’t investing at all, it’s highly speculative fortune-telling. Value investing doesn’t need to be about forecasting anything. It’s about identifying obvious value today and then just waiting for the magic of mean reversion to do its thing. Value investing begins and ends with the price on offer. If it’s a quality business, a cheap price is a good one.

Oaktree Capital’s Howard Marks, one of the all-time great investors, states that

“For a value investor, price has to be the starting point. It has been demonstrated time and time again that no asset is so good that it can’t become a bad investment if bought at too high a price. And there are few assets so bad that they can’t be a good investment when bought cheap enough.”

In other words, there are no bad assets – just bad prices. The key determinant between your investment success and investment failure is the price you elect to pay for what you own. And we use the word ‘elect’ advisedly – nobody ever forces you to buy anything, at any price. The market always offers you a choice.

Price is everything and price is in many respects the only thing that matters. Everything else is secondary.

It has taken this correspondent a quarter of a century of working in the capital markets to learn this lesson.

Whenever we pitch our value fund to prospective investors, we always include the following chart. It is taken from James O’Shaughnessy’s ‘What works on Wall Street’ (McGraw-Hill 2011). It is perhaps the definitive proof of the long term success of value investing.

O’Shaughnessy screened the entire US stock market by valuation. He selected the 50 highest rated stocks on the basis of price to sales ratio (High PSR) and then the 50 lowest rated stocks on the same basis. He did the same for price to cashflow, price to book and price to earnings (PE). He then rolled the clock forward for half a century and annually rebalanced these lists so that they continually comprised the 50 most expensive stocks and the 50 cheapest stocks by each metric. The results are shown below.

Take price / book – the share price of a company by comparison to its underlying inherent (or book) value per share.

If you started out with the 50 most expensive US stocks on a price / book basis, and then continually rebalanced that list of 50 stocks so that you always owned the most expensive 50 stocks, a portfolio with a starting value of $10,000 would, after 52 years, be worth $267,147.

Which sounds great, or at least okay, until you see what you could have made by owning the cheapest stocks instead.

If you had held the 50 cheapest stocks as expressed by their price / book ratio, and continually rebalanced that portfolio every year so that you stayed with the 50 cheapest stocks, your portfolio of $10,000 would, after 52 years, be worth $22,004,691.

If you come across a more compelling display of the merits of value investing, please let us know, because we happen to doubt whether such evidence exists. This is dynamite stuff.

From O’Shaughnessy himself:

“When you look back as far as 80 years for which we have data, rather than moving about without rhyme or reason, the stock market methodically rewards certain investment strategies while punishing others. There’s no question the value-based strategies that work over long periods of time don’t work all the time, but history shows that after what turn out to be relatively brief periods when other things seem to be all that matter, the market reasserts its preference for value, often with ferocity. My basic premise is that given all that, investors can do much better than the market if they consistently use time-tested strategies that are based on sensible, rational, value-based methods for selecting stocks.”

Lest you think we’re being partial, here’s another study.

Fund managers Research Affiliates recently published a study entitled ‘How not to get fired with smart beta investing’.

They crunched the numbers for 50 years, and found that certain investment strategies added value versus a market capitalisation weighted benchmark (such as the S&P 500 index), and other strategies destroyed value versus a market cap-weighted benchmark.

Research Affiliates split the market up into four ‘styles’: value (i.e. cheap companies); momentum (companies whose share prices are rising sharply in price); quality (i.e. relatively resilient and economically enduring companies in sectors like pharmaceuticals) and finally growth (i.e. expensive companies, such as today’s so-called FANGs – the likes of Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google).

What they found was intriguing, and extremely useful for investors looking for an edge.

Two styles added value consistently (Research Affiliates described them as ‘Robust’) – generating additional value of between fractions of a percent and over 2 percent annually, versus the benchmark. Those styles were value, and then momentum. We would indeed go further: we happen to think that value and momentum are, between them, the only ways of sustainably making money from the stock market over the medium term. Value is clearly our favourite, but we acknowledge that momentum can also work, which is why we also use systematic trend-following funds as part of our investible universe.

Two percent added value per annum may not seem like much, but over time it compounds wonderfully, as James O’Shaughnessy’s table shows.

Two styles, on the other hand, destroyed value versus the benchmark (Research Affiliates described them as ‘Non-Robust’; we would have used less charitable language). One of them was ‘quality’ – in essence, overpaying for companies, and the other was ‘growth’ – again, effectively, overpaying for (temporarily) high earnings, or at least the potential for high earnings in the future.

Given that both O’Shaughnessy’s and Research Affiliates’ studies comprised over 50 years’ worth of returns, we think we can take them seriously. These are statistically meaningful periods of time.

Research Affiliates than go on to make an additional point which is truly incredible. Although they show that value investing is clearly the single most successful investment strategy over the medium to longer term, they also point out that value investing is at the same time the investment strategy that is most likely to get a financial adviser fired by his client for recommending it. Their study, again using annualized value added, is shown below.

(The reference to 4 Orlandos, if you’re interested, shows the results of a random portfolio of stocks selected by Orlando, the stock-picking cat.)

If this study doesn’t prove that investors are irrational, nothing will. The reason that investors will tend to fire value managers is that they don’t have the stamina to accept sub-par performance in the short run. The irony, of course, is that no strategy on this planet works consistently, year in, year out – but value comes closest to that objective over the medium term. But the average investor, living in the moment, doesn’t have the patience to see it through.

When we first came across the O’Shaughnessy study, we nearly fell off our chair. When we came across the Research Affiliates study, we nearly fell off the floor.

At the risk of labouring the point, price is pretty much the only thing that matters. In terms of the listed equity markets, try and identify high quality businesses, with principled, shareholder-friendly management, and then try and buy them when their shares are available at close to or, ideally, below their inherent value, or book value. This is the investment methodology that drives every investment we make. And because the US stock market happens to be abnormally expensive, it makes perfect sense to cast one’s net as widely as possible internationally, because nobody is forcing us to indulge in home country bias. If the value happens to be in Asia (which it largely does, in our view, today), then start hunting for value opportunities there. Caveat: per Research Affiliates’ second observation, be prepared to wait. Value investing does not offer instant gratification. The great Canadian value investor Peter Cundill was spot on when he said,

“The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. THE MAJORITY OF INVESTORS DO NOT POSSESS THIS CHARACTERISTIC.”

Focus on price, and then try and be patient.

But human beings are suckers for stories. Our lives are driven by narratives. In the words of the X-Files, we want to believe. Anything to do with valuation gets thrown under the bus as being irrelevant. The story is more compelling than the price.

We suggest that the average investor is motivated more strongly by stories – by hope, if you like – than by anything else. And Wall Street, CNBC and our investment media en masse are more than happy to keep fuelling this fire. Narratives engage our emotions more than any amount of rational analysis. The great insight of the classical economists is that economic interaction takes place between human beings with a tendency towards the irrational. All of modern portfolio theory derives from a false premise, that markets are efficient. Well, they will be when we are. And that is going to be: never. Value investing amounts to a process whereby rational and patient investors take money away from irrational, impatient and credulous ones.

The beginning of the end ?

Our strong suspicion is that we are very close to the tail end of a monumental rally that has taken developed world stock and bond markets, including but not limited to those of the US, to dangerously unsustainable levels. This view is shared by strategist David Murrin.

Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted p/e (or CAPE) for the S&P 500 stock index is now – at over 29 times and despite the recent correction – essentially at the same level as on Black Tuesday 1929. Its long run average is less than 17 times.

Robert Shiller CAPE ratio, 1880 – 2022

Source: http://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe/

So to anyone who believes in long term reversion to the mean, US stocks remain heavily overvalued.

The so-called FANGs (the likes of Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google) have been dominant drivers of recent stock market gains. Their popularity is akin to that of the so-called Nifty Fifty of the early 1970s – just before they cratered.

Perhaps most ominously, the Fed is in the early stages of normalising US interest rates. We are now in the earliest phase of Quantitative Tightening. And there is an iron clad relationship between interest rates and bond prices. If interest rates go up, bond prices go down.

What could possibly go wrong ?

Clearly, plenty of things could.

But don’t confuse this for a counsel of despair. The beauty of value investing is that if we’ve done our homework well enough, any market decline makes our favoured securities even better value; what Benjamin Graham calls their “margin of safety” gets even bigger. This is intuitively obvious, given that we are trying to find dollar bills for 40 cents. If those dollar bills suddenly trade at 30 cents, are they more or less attractive than they were at 40 ? In the immortal words of fund manager Cullen Roche,

“The stock market is the only market where things go on sale and all the customers run out of the store.”

It makes sense to panic if the price of your overpriced growth-at-any-cost stocks starts to weaken. Since all those stocks had going for them in the first place was momentum, if the momentum of the market starts to turn, you probably should be running for the exit.

But at a time when the prices of so many financial assets – stocks, bonds, property – are juiced by trillions of dollars’ worth of free money and QE, genuinely defensive value investments from around the world, selected on an entirely unconstrained basis, are about the only public market investments worth making.

Last word this week goes to Howard Marks:

“If I had to identify a single key to consistently successful investing, I’d say it’s “cheapness”. Buying at low prices relative to intrinsic value (rigorously and conservatively derived) holds the key to earning dependably high returns, limiting risk and minimizing losses. It’s not the only thing that matters – obviously – but it’s something for which there is no substitute.”

Go forth and prosper !

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price