The 1970s was a decade dominated by the minor key in politics, culture, and financial markets. Whereas the 1960s had showered open minds with free love, the counterculture and a sense of possibilities, the 1970s offered up Watergate, the messy end of the Vietnam War, two Arab ‘oil shocks’ and grinding, stagflationary bear markets that savaged the prices of stocks and bonds.

As a natural barometer of the popular mood, Hollywood reflected these concerns. The 1970s was nevertheless a golden age for film, a true blockbuster era, where commercial success and quality entertainment could cheerfully co-exist. The decade that gave the world the religious horrors of ‘The Exorcist’ also gave us the two ‘Godfather’ movies, ‘Jaws’, ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’..

But it was the ‘fictional’ machinations of the supposed military-industrial complex, the conspiracy thrillers, that intrigued this correspondent the most. We would submit that the 1970s was defined most acutely by films like ‘All The President’s Men’, ‘Capricorn One’ (suggesting none too subtly that the moon landings had been faked), Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘The Conversation’, ‘Three Days of the Condor’, and ‘The Parallax View’.

But above any of them, the conspiracy movie that we found most affecting was ‘The China Syndrome’, starring Jane Fonda, Jack Lemmon and Michael Douglas, who also produced it.

The fiction

The China Syndrome is all the more powerful for being based on a true story. Of a sort. Its plot has a TV reporter (Fonda) and her militant cameraman (a particularly hirsute Douglas) discovering a near fatal accident at a nuclear power plant. The plant manager (Lemmon, in an outstanding straight dramatic role, for once) goes on to discover the short cuts that the nuclear plant’s construction company has undertaken to save costs – nearly leading to disaster.

The China Syndrome is remarkable in that it went on general release (on March 16th 1979) 12 days before the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania that it uncannily resembled.

A nuclear power station works as follows. Within a containment structure, uranium is used to turn water into steam, which then drives a turbine generator to produce electricity. Control rods, composed of elements like boron, silver or cadmium, are used to manage the fission rate of the uranium. Water is also used as a coolant to control the fissile process.

In the film, the plant’s managers misread a stuck water gauge suggesting that the water level is too high. It is actually dangerously low. Being unaware of this, they vent radioactive water to protect the integrity of the containment tower. But this risks exposing the uranium core. If the core is exposed, it overheats – and runs the risk of melting down, conceivably all the way through the earth to China, hence the film’s title.

The reality

On March 28th 1979, a small relief valve on one of Three Mile Island’s reactor plant pressurizer systems stuck open. This allowed large amounts of reactor coolant to escape. A hidden indicator light led to an operator manually overriding the plant’s automatic emergency cooling system – in an eerie example of life imitating art, he believed there was too much coolant water present in the reactor, not too little.

Very early on at Three Mile Island, the control rods were fully inserted (what’s called a SCRAM event in the film), but waste atoms in the fuel were still capable of producing roughly 5% of full-power heat for up to 36 hours after the chain reaction had finished. Without sufficient water to carry away this heat, Three Mile Island’s fuel cell overheated.

Shortly after the core was re-immersed in water, a bubble of hydrogen began to form inside the reactor above the damaged core. On the second day of the accident, hydrogen was detected inside the reactor building itself. The operators at the plant duly reported this to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, confident that the reactor’s integrity had not been compromised. But officials in Washington over-reacted, incorrectly assuming that the bubble could explode and rupture the six-inch thick steel containment vessel.

The NRC then reported, in error, to the news media that a potentially explosive hydrogen bubble had formed in the reactor. The response was predictable. All hell broke loose.

That evening, Walter Cronkite made the following announcement on live television:

“The world has never known a day quite like today. It faced the considerable uncertainties and dangers of the worst nuclear power plant accident of the atomic age. And the horror tonight is that it could get much worse. The potential is there for the ultimate risk of meltdown at Three Mile Island..”

Governor Thornburgh of Pennsylvania advised pregnant women and women of child-bearing age within 50 miles of TMI to consider leaving the area.

Roughly 140,000 people undertook a voluntary mass evacuation.

Communications between the reactor operators, the NRC, the State of Pennsylvania and the news media fell into total disarray.

TMI would cast a shadow across America for the next five years. Hoping to quell rising public hysteria, the NRC imposed a moratorium on building new nuclear plants. News reports would routinely refer to the radioactive releases from TMI as “fallout” – thus inextricably linking the accident at the plant to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

An internal inspection, delayed by litigation until 1984, revealed that 52% of the reactor’s uranium fuel had completely melted. Another 40% of the fuel around the core had partially melted. Only a ring of fuel cells on the periphery of the core, roughly 8% of the total, was “merely” heat-damaged. Whereas President Carter had described the incident as a “near meltdown”, it had actually been a genuine meltdown, and a severe one. But there had been no ‘China syndrome’, no uncontrolled melting through the earth’s core, no thousands of radiation-related deaths.

Outrunning complexity

The sociologist Charles Perrow wrote an extensive article for ‘Society’ magazine, published in July 1981, titled ‘Normal accident at Three Mile Island’.

As the title implies, Perrow found nothing exceptional about the circumstances that led to the meltdown:

“Normal accidents emerge from the characteristics of the systems themselves. They cannot be prevented. They are unanticipated. It is not feasible to train, design or build in such a way as to anticipate all eventualities in complex systems where the parts are tightly coupled. They are incomprehensible when they occur. That is why operators usually assume something else is happening, something that they understand, and act accordingly. Being incomprehensible, they are partially uncontrollable. That is why operator intervention is often irrelevant. Safety systems, backup systems, quality equipment, and good training all help prevent accidents and minimize catastrophe, but the complexity of systems outruns all controls.” [Emphasis ours.]

The British economist John Maynard Keynes wrote in an essay, “The Great Slump of 1930”:

“..But today we have involved ourselves in a colossal muddle, having blundered in the control of a delicate machine, the working of which we do not understand. The result is that our possibilities of wealth may run to waste for a time – perhaps for a long time.”

On the latter point, he was undoubtedly right – the Great Depression would run on for the best part of a decade. To some observers (ourselves included), the US was not lifted out of depression and economic stagnation by Roosevelt’s New Deal. It was lifted out of economic hardship by America’s entry into the Second World War.

But it’s the first part of the quote that casts the real shadow. Keynes’ metaphor of economy-as-machine is not just inaccurate, it’s wholly inappropriate. The economy is not some simple machine that can be driven back to equilibrium (an illusory state that doesn’t even exist, we would suggest, in the real economy). The economy is as complex as human nature because the economy is human interaction on a global scale. The economy is us. And by extension, the financial markets are us, too.

The new China syndrome

One of our favourite analysts, Russell Napier, formerly with the Asian brokerage CLSA, has previously compared China’s efforts to control its markets to that of a falconer trying to manage a wild falcon. It’s an allusion to one of the Irish poet W. B. Yeats’ most unsettling poems, ‘The Second Coming’. This is verse written in the aftermath of World War I, and which has provided financial commentators with a rich vein of metaphor over the recent years of crisis. It begins as follows:

“Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned.

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity..”

In Russell’s world view there are two competing forces. What is left of free markets wants deflation, and a giant reset of a bankrupt system. The free markets want to purge the system of bad players, and zombie businesses. This amounts to debt deflation, and what would amount to the largest debt deflation in history.

But dead set against this deflation is the State, be it that of China, or North America, or the UK, or the euro zone, or Japan. The economic attitude is the same, irrespective of geography. The State cannot survive entrenched deflation. The State has to inflate. Hence QE, TARP, ZIRP, NIRP and a thousand other mindless acronyms that betoken the new China syndrome.

Russell Napier:

“Any political fiat, when monetary fiat fails, will be tantamount, in some way or other, to an attempt to directly control the allocation of capital/savings. History shows that this commences a giant game of hide-and-seek, and while gold may shine brightly it is also moved freely in briefcases and is easily hidden. Paper assets are easily tracked, discovered, conscripted and ultimately denuded in value. For gold to rise while the USD also rises signals that investors are beginning to see through the terrible burden on the price of the shiny stuff from ever-rising real rates of interest extant since 2011. Real rates have further to rise but a few more days of a strong USD and a strong gold price means gold has probably entered a bull market that should last for decades rather than years; its value boosted initially by its ability to avoid conscription, but underpinned by the authorities’ mass mobilization of resources to ultimately generate inflation.

“From 2009-2015 investors were well paid, at least in the developed world, to believe the most impossible of Alice Through The Looking Glass’s six impossible things before breakfast: that central bankers can subvert the desires, wishes, greed and fear of millions of people who set prices every day through their actions.”

In ‘the new China syndrome’, the State believes that it can control financial markets. We have had years’ worth of explicit, State-controlled inflationism, and thus far nothing tangible to show for it other than a widening in the gulf between those with capital and those without. The asset rich have got richer (in nominal terms, at least), and those without assets have likely found their employment prospects have meanwhile got worse, not better. The situation is compounded in Europe by a flood of migration that is tearing the fabric of social order.

Before we turn to the specific investment implications of ‘the new China syndrome’, we quote briefly the fund managers of Nevsky Capital. Nevsky Capital was set up by two emerging market specialists, Martin Taylor and Nick Barnes, who had previously worked at Baring Asset Management and then Thames River Capital.

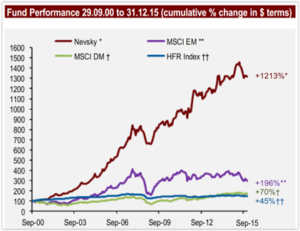

The Nevsky Fund was a $1.5 billion global equity long / short fund that Messrs Taylor and Barnes elected to wind up at the start of 2016. Unlike many other hedge fund suspensions, Nevsky decided to close down at the top of its game. Its track record is shown below:

(Source: Nevsky Capital LLP, Bloomberg)

Over the course of its 15 year life, Nevsky returned average annualised returns of 18.4%. Those returns are thoroughly remarkable. Extraordinarily impressive.

By way of comparison, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index (MSCI EM) returned, on average, 7.4% per annum. MSCI Developed Markets (MSCI DM) returned just 3.5% per annum.

In a letter to their investors, Nevsky described their decision to close as follows:

“The decision to stop managing the Fund, after just over 15 years, has been a very difficult one. This decision has been driven by a growing recent awareness that certain features of the current market environment, which we believe might persist for a considerable period of time, are inconsistent with the achievement of our goal of providing satisfactory risk-adjusted absolute returns for you, our clients.”

Among those ‘certain features’ of the current market environment:

- The lack of access to “transparent and truthfully compiled data” – especially in the emerging markets like China that Nevsky specialised in;

- The lack of logical decision-making by central bankers;

- An inability to achieve “a clear understanding of the positioning of other investors in the market” in order to try and assess what is in the price, and where fair value might be said to exist;

- The lack of “a reasonable level of divergence in equity prices between different geographies and sectors and the existence of constantly evolving, but logical, inter-relationships between these different asset classes”. Or, to coin a phrase, the lack of the normal operation of free markets.

In summary, a highly successful investment fund elected to shut itself down because its managers found themselves unable to function within the world of ‘the new China syndrome’.

Nevsky are not alone. Other international managers have recently highlighted what they perceive as a key shift in the investment landscape, most notably in China, where:

- State control (a.k.a. market interference) is increasing

- Geopolitical tensions are heightening

- The property market seems moribund

- The debt outlook is getting cloudier

- Genuine growth has all but disappeared.

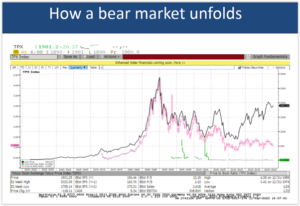

The chart below may yet prove instructive with regard to China. It shows how Japan’s stock market, as defined by the Topix index (in black) peaked – after a grotesque property bubble – in 1989 – and how every subsequent counter-trend rally ended up as a false dawn that crushed investor hopes in any Japanese equity market recovery. Could China’s stock market end up replicating the Japanese experience – reflecting a lost decade, or more ?

Source: Bloomberg.

At the time that Nevsky folded its tents, the financial authorities had not yet succeeded in triggering inflation. Things have clearly changed over the subsequent years of unhinged monetary stimulus. Which is why every investor of means should own gold.

But the gold market has become bifurcated. ‘Paper gold’ may have incurred periods of underperformance; meanwhile, the physical asset itself, bullion, has simply abandoned western inventories and headed in its own migration, to Asia. It may never return. In an environment where the risk of systemic financial distress is a real and pressing concern, gold is a must-own investment, preferably held offshore, or at least well outside the financial system itself.

Next, the historic cornerstones of prudent asset diversification, bonds, are no longer fit for purpose. An asset reflecting risk-free returns has become distorted, by ‘the new China syndrome’ and explicit State price suppression, into return-free risk. Rather than own bonds as a bellwether ‘safe haven’ investment, we favour the use of systematic trend-following funds.

And when it comes to what has traditionally been the core of any private investor’s long term portfolio, namely common stocks, it surely only makes sense to hold shares of businesses of unimpeachable quality, and management quality, bought at some kind of discount to their inherent worth. In a word, ‘value’. Years of ‘the new China syndrome’ have hopelessly distorted valuations in stock markets too, but we remain convinced that pockets of value exist for those investors patient and most of all open-minded enough to pursue them. As things stand, we find commodity-related businesses the most compellingly valued in the world. We positively salivate at their current unpopularity.

We have to abandon indices and benchmarks, though, because today they constitute the worst sort of ‘herd thinking’, forcing investors into ever narrower and more expensive confines of the financial markets.

The last couple of years have clearly constituted a tricky period for all stock markets, and even the ‘value’ stocks that we favour have not been immune to the downtrend. But the distinction between speculative ‘growth’ stocks and genuine ‘value’ opportunities is as follows: when the bloom comes off the rose (which we would suggest it now has), ‘growth’ stocks will sink through any notional support levels. Proper ‘value’, on the other hand, doesn’t get riskier as it gets cheaper, it simply gets more attractive.

The attractions of value can often be hidden by psychology. When stock markets suddenly collapse, few people feel like buying. But we highlight the following words from Ben Graham, drawn from his classic 1949 study, ‘The Intelligent Investor’:

“Common stocks are generally viewed as being highly speculative and therefore unsafe; they have declined fairly substantially from the high levels of 1946, but instead of attracting investors to them because of their reasonable prices, the fall has had the opposite effect of undermining confidence in equity securities.”

(Ben Graham also famously, and rightly, observed that our biggest enemy when it comes to investment is likely to be ourselves.)

A recent review of ‘The China Syndrome’ describes the film as “a thought provoking, and compelling drama that absolutely encapsulates both the conspiratorial nature of corporate greed, and the insipid nature of the media when controlling and manipulating the truth.”

Very 2023.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you, too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

The 1970s was a decade dominated by the minor key in politics, culture, and financial markets. Whereas the 1960s had showered open minds with free love, the counterculture and a sense of possibilities, the 1970s offered up Watergate, the messy end of the Vietnam War, two Arab ‘oil shocks’ and grinding, stagflationary bear markets that savaged the prices of stocks and bonds.

As a natural barometer of the popular mood, Hollywood reflected these concerns. The 1970s was nevertheless a golden age for film, a true blockbuster era, where commercial success and quality entertainment could cheerfully co-exist. The decade that gave the world the religious horrors of ‘The Exorcist’ also gave us the two ‘Godfather’ movies, ‘Jaws’, ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’..

But it was the ‘fictional’ machinations of the supposed military-industrial complex, the conspiracy thrillers, that intrigued this correspondent the most. We would submit that the 1970s was defined most acutely by films like ‘All The President’s Men’, ‘Capricorn One’ (suggesting none too subtly that the moon landings had been faked), Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘The Conversation’, ‘Three Days of the Condor’, and ‘The Parallax View’.

But above any of them, the conspiracy movie that we found most affecting was ‘The China Syndrome’, starring Jane Fonda, Jack Lemmon and Michael Douglas, who also produced it.

The fiction

The China Syndrome is all the more powerful for being based on a true story. Of a sort. Its plot has a TV reporter (Fonda) and her militant cameraman (a particularly hirsute Douglas) discovering a near fatal accident at a nuclear power plant. The plant manager (Lemmon, in an outstanding straight dramatic role, for once) goes on to discover the short cuts that the nuclear plant’s construction company has undertaken to save costs – nearly leading to disaster.

The China Syndrome is remarkable in that it went on general release (on March 16th 1979) 12 days before the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania that it uncannily resembled.

A nuclear power station works as follows. Within a containment structure, uranium is used to turn water into steam, which then drives a turbine generator to produce electricity. Control rods, composed of elements like boron, silver or cadmium, are used to manage the fission rate of the uranium. Water is also used as a coolant to control the fissile process.

In the film, the plant’s managers misread a stuck water gauge suggesting that the water level is too high. It is actually dangerously low. Being unaware of this, they vent radioactive water to protect the integrity of the containment tower. But this risks exposing the uranium core. If the core is exposed, it overheats – and runs the risk of melting down, conceivably all the way through the earth to China, hence the film’s title.

The reality

On March 28th 1979, a small relief valve on one of Three Mile Island’s reactor plant pressurizer systems stuck open. This allowed large amounts of reactor coolant to escape. A hidden indicator light led to an operator manually overriding the plant’s automatic emergency cooling system – in an eerie example of life imitating art, he believed there was too much coolant water present in the reactor, not too little.

Very early on at Three Mile Island, the control rods were fully inserted (what’s called a SCRAM event in the film), but waste atoms in the fuel were still capable of producing roughly 5% of full-power heat for up to 36 hours after the chain reaction had finished. Without sufficient water to carry away this heat, Three Mile Island’s fuel cell overheated.

Shortly after the core was re-immersed in water, a bubble of hydrogen began to form inside the reactor above the damaged core. On the second day of the accident, hydrogen was detected inside the reactor building itself. The operators at the plant duly reported this to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, confident that the reactor’s integrity had not been compromised. But officials in Washington over-reacted, incorrectly assuming that the bubble could explode and rupture the six-inch thick steel containment vessel.

The NRC then reported, in error, to the news media that a potentially explosive hydrogen bubble had formed in the reactor. The response was predictable. All hell broke loose.

That evening, Walter Cronkite made the following announcement on live television:

“The world has never known a day quite like today. It faced the considerable uncertainties and dangers of the worst nuclear power plant accident of the atomic age. And the horror tonight is that it could get much worse. The potential is there for the ultimate risk of meltdown at Three Mile Island..”

Governor Thornburgh of Pennsylvania advised pregnant women and women of child-bearing age within 50 miles of TMI to consider leaving the area.

Roughly 140,000 people undertook a voluntary mass evacuation.

Communications between the reactor operators, the NRC, the State of Pennsylvania and the news media fell into total disarray.

TMI would cast a shadow across America for the next five years. Hoping to quell rising public hysteria, the NRC imposed a moratorium on building new nuclear plants. News reports would routinely refer to the radioactive releases from TMI as “fallout” – thus inextricably linking the accident at the plant to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

An internal inspection, delayed by litigation until 1984, revealed that 52% of the reactor’s uranium fuel had completely melted. Another 40% of the fuel around the core had partially melted. Only a ring of fuel cells on the periphery of the core, roughly 8% of the total, was “merely” heat-damaged. Whereas President Carter had described the incident as a “near meltdown”, it had actually been a genuine meltdown, and a severe one. But there had been no ‘China syndrome’, no uncontrolled melting through the earth’s core, no thousands of radiation-related deaths.

Outrunning complexity

The sociologist Charles Perrow wrote an extensive article for ‘Society’ magazine, published in July 1981, titled ‘Normal accident at Three Mile Island’.

As the title implies, Perrow found nothing exceptional about the circumstances that led to the meltdown:

“Normal accidents emerge from the characteristics of the systems themselves. They cannot be prevented. They are unanticipated. It is not feasible to train, design or build in such a way as to anticipate all eventualities in complex systems where the parts are tightly coupled. They are incomprehensible when they occur. That is why operators usually assume something else is happening, something that they understand, and act accordingly. Being incomprehensible, they are partially uncontrollable. That is why operator intervention is often irrelevant. Safety systems, backup systems, quality equipment, and good training all help prevent accidents and minimize catastrophe, but the complexity of systems outruns all controls.” [Emphasis ours.]

The British economist John Maynard Keynes wrote in an essay, “The Great Slump of 1930”:

“..But today we have involved ourselves in a colossal muddle, having blundered in the control of a delicate machine, the working of which we do not understand. The result is that our possibilities of wealth may run to waste for a time – perhaps for a long time.”

On the latter point, he was undoubtedly right – the Great Depression would run on for the best part of a decade. To some observers (ourselves included), the US was not lifted out of depression and economic stagnation by Roosevelt’s New Deal. It was lifted out of economic hardship by America’s entry into the Second World War.

But it’s the first part of the quote that casts the real shadow. Keynes’ metaphor of economy-as-machine is not just inaccurate, it’s wholly inappropriate. The economy is not some simple machine that can be driven back to equilibrium (an illusory state that doesn’t even exist, we would suggest, in the real economy). The economy is as complex as human nature because the economy is human interaction on a global scale. The economy is us. And by extension, the financial markets are us, too.

The new China syndrome

One of our favourite analysts, Russell Napier, formerly with the Asian brokerage CLSA, has previously compared China’s efforts to control its markets to that of a falconer trying to manage a wild falcon. It’s an allusion to one of the Irish poet W. B. Yeats’ most unsettling poems, ‘The Second Coming’. This is verse written in the aftermath of World War I, and which has provided financial commentators with a rich vein of metaphor over the recent years of crisis. It begins as follows:

“Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned.

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity..”

In Russell’s world view there are two competing forces. What is left of free markets wants deflation, and a giant reset of a bankrupt system. The free markets want to purge the system of bad players, and zombie businesses. This amounts to debt deflation, and what would amount to the largest debt deflation in history.

But dead set against this deflation is the State, be it that of China, or North America, or the UK, or the euro zone, or Japan. The economic attitude is the same, irrespective of geography. The State cannot survive entrenched deflation. The State has to inflate. Hence QE, TARP, ZIRP, NIRP and a thousand other mindless acronyms that betoken the new China syndrome.

Russell Napier:

“Any political fiat, when monetary fiat fails, will be tantamount, in some way or other, to an attempt to directly control the allocation of capital/savings. History shows that this commences a giant game of hide-and-seek, and while gold may shine brightly it is also moved freely in briefcases and is easily hidden. Paper assets are easily tracked, discovered, conscripted and ultimately denuded in value. For gold to rise while the USD also rises signals that investors are beginning to see through the terrible burden on the price of the shiny stuff from ever-rising real rates of interest extant since 2011. Real rates have further to rise but a few more days of a strong USD and a strong gold price means gold has probably entered a bull market that should last for decades rather than years; its value boosted initially by its ability to avoid conscription, but underpinned by the authorities’ mass mobilization of resources to ultimately generate inflation.

“From 2009-2015 investors were well paid, at least in the developed world, to believe the most impossible of Alice Through The Looking Glass’s six impossible things before breakfast: that central bankers can subvert the desires, wishes, greed and fear of millions of people who set prices every day through their actions.”

In ‘the new China syndrome’, the State believes that it can control financial markets. We have had years’ worth of explicit, State-controlled inflationism, and thus far nothing tangible to show for it other than a widening in the gulf between those with capital and those without. The asset rich have got richer (in nominal terms, at least), and those without assets have likely found their employment prospects have meanwhile got worse, not better. The situation is compounded in Europe by a flood of migration that is tearing the fabric of social order.

Before we turn to the specific investment implications of ‘the new China syndrome’, we quote briefly the fund managers of Nevsky Capital. Nevsky Capital was set up by two emerging market specialists, Martin Taylor and Nick Barnes, who had previously worked at Baring Asset Management and then Thames River Capital.

The Nevsky Fund was a $1.5 billion global equity long / short fund that Messrs Taylor and Barnes elected to wind up at the start of 2016. Unlike many other hedge fund suspensions, Nevsky decided to close down at the top of its game. Its track record is shown below:

(Source: Nevsky Capital LLP, Bloomberg)

Over the course of its 15 year life, Nevsky returned average annualised returns of 18.4%. Those returns are thoroughly remarkable. Extraordinarily impressive.

By way of comparison, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index (MSCI EM) returned, on average, 7.4% per annum. MSCI Developed Markets (MSCI DM) returned just 3.5% per annum.

In a letter to their investors, Nevsky described their decision to close as follows:

“The decision to stop managing the Fund, after just over 15 years, has been a very difficult one. This decision has been driven by a growing recent awareness that certain features of the current market environment, which we believe might persist for a considerable period of time, are inconsistent with the achievement of our goal of providing satisfactory risk-adjusted absolute returns for you, our clients.”

Among those ‘certain features’ of the current market environment:

In summary, a highly successful investment fund elected to shut itself down because its managers found themselves unable to function within the world of ‘the new China syndrome’.

Nevsky are not alone. Other international managers have recently highlighted what they perceive as a key shift in the investment landscape, most notably in China, where:

The chart below may yet prove instructive with regard to China. It shows how Japan’s stock market, as defined by the Topix index (in black) peaked – after a grotesque property bubble – in 1989 – and how every subsequent counter-trend rally ended up as a false dawn that crushed investor hopes in any Japanese equity market recovery. Could China’s stock market end up replicating the Japanese experience – reflecting a lost decade, or more ?

Source: Bloomberg.

At the time that Nevsky folded its tents, the financial authorities had not yet succeeded in triggering inflation. Things have clearly changed over the subsequent years of unhinged monetary stimulus. Which is why every investor of means should own gold.

But the gold market has become bifurcated. ‘Paper gold’ may have incurred periods of underperformance; meanwhile, the physical asset itself, bullion, has simply abandoned western inventories and headed in its own migration, to Asia. It may never return. In an environment where the risk of systemic financial distress is a real and pressing concern, gold is a must-own investment, preferably held offshore, or at least well outside the financial system itself.

Next, the historic cornerstones of prudent asset diversification, bonds, are no longer fit for purpose. An asset reflecting risk-free returns has become distorted, by ‘the new China syndrome’ and explicit State price suppression, into return-free risk. Rather than own bonds as a bellwether ‘safe haven’ investment, we favour the use of systematic trend-following funds.

And when it comes to what has traditionally been the core of any private investor’s long term portfolio, namely common stocks, it surely only makes sense to hold shares of businesses of unimpeachable quality, and management quality, bought at some kind of discount to their inherent worth. In a word, ‘value’. Years of ‘the new China syndrome’ have hopelessly distorted valuations in stock markets too, but we remain convinced that pockets of value exist for those investors patient and most of all open-minded enough to pursue them. As things stand, we find commodity-related businesses the most compellingly valued in the world. We positively salivate at their current unpopularity.

We have to abandon indices and benchmarks, though, because today they constitute the worst sort of ‘herd thinking’, forcing investors into ever narrower and more expensive confines of the financial markets.

The last couple of years have clearly constituted a tricky period for all stock markets, and even the ‘value’ stocks that we favour have not been immune to the downtrend. But the distinction between speculative ‘growth’ stocks and genuine ‘value’ opportunities is as follows: when the bloom comes off the rose (which we would suggest it now has), ‘growth’ stocks will sink through any notional support levels. Proper ‘value’, on the other hand, doesn’t get riskier as it gets cheaper, it simply gets more attractive.

The attractions of value can often be hidden by psychology. When stock markets suddenly collapse, few people feel like buying. But we highlight the following words from Ben Graham, drawn from his classic 1949 study, ‘The Intelligent Investor’:

“Common stocks are generally viewed as being highly speculative and therefore unsafe; they have declined fairly substantially from the high levels of 1946, but instead of attracting investors to them because of their reasonable prices, the fall has had the opposite effect of undermining confidence in equity securities.”

(Ben Graham also famously, and rightly, observed that our biggest enemy when it comes to investment is likely to be ourselves.)

A recent review of ‘The China Syndrome’ describes the film as “a thought provoking, and compelling drama that absolutely encapsulates both the conspiratorial nature of corporate greed, and the insipid nature of the media when controlling and manipulating the truth.”

Very 2023.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you, too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price