The most expensive purchase you will ever make ? It is not, as you might think, your home. Nor is it your car, or your children’s or grandchildren’s education. It is not healthcare, though it may, in part, be some of these things.

The most expensive purchase you will ever make is your government.

As Dominic Frisby points out in his excellent book on the history of tax, Daylight Robbery,

“For a typical British middle-class professional over the course of his or her life, the [government tax] bill totals £3.6 million ($5 million) – considerably more than the typical house. You will spend a full 20 years of your life or more in obligatory service to the state. On a time basis, the state owns as much of your labour as the feudal lord did that of the medieval serf, who gave half his working week to farm the land of his lord in exchange for his protection. In exchange, you receive the protection of the state and its services: defence, healthcare, education and so on, for yourself and others. Some people are content with today’s arrangement, others are not, but whatever your political leanings, you have no choice. If you want to work for a living, you must work for the state as well as yourself. We are not as free as we may think we are.”

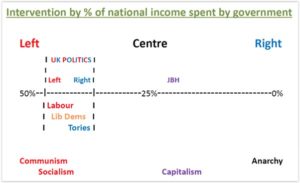

It was not always so. As the economist John Hearn, who teaches at the London Institute of Banking and Finance, points out, at the beginning of the 20th Century, the UK government was spending about 10% of the nation’s income. But then came the First World War, and the trend has been upwards ever since. As John also points out, not only is government spending in the UK now at or above 50% of national income, but perhaps more alarmingly, there is no real difference in spending plans between each of the major political parties. Whether you support the Conservatives, Labour or the Lib Dems, the age of supposed austerity is well and truly over, as politicians scramble to bribe us all with our own money.

Source: The London Institute of Banking and Finance / John Hearn.

John’s preference for government spending is shown in his chart above (denoted as ‘JBH’), at somewhere less than 25% of UK GDP. Ours, too. Why not zero ? Because there are certain things that only government can provide – things like street lighting and national defence, because the market either can’t or won’t provide them itself.

John goes on to ask: does the economy even need politics or politicians ? Unfortunately, the answer is a reluctant ‘yes’. To understand why, we first need to examine the difference between the profit motive and the vote motive.

Businesses respond to the profit motive. The profit motive and an unconstrained free market create efficiency. In September 1989, Boris Yeltsin, newly elected to the Soviet parliament and the Supreme Soviet, visited the Johnson Space Centre in Houston, Texas. He was probably impressed by what he saw there. He then went on an impromptu visit to a Randall’s supermarket. That was when his eyes really nearly popped out of his skull. As he toured aisles overflowing with goods and produce, he told his entourage that if the Russian people could see the condition of US supermarkets, “there would be a revolution”. As he later wrote,

“When I saw those shelves crammed with hundreds, thousands of cans, cartons and goods of every possible sort, for the first time I felt quite frankly sick with despair for the Soviet people. That such a potentially super-rich country as ours has been brought to a state of such poverty! It is terrible to think of it.”

Within two months, the Berlin Wall had started to come down.

Politicians, on the other hand, are guided primarily by the vote motive – the requirement to be thinking in almost constant terms of re-election. Inasmuch as there is any long term perspective for a politician or MP, it is driven by the electoral cycle.

The vote motive creates inefficiency.

So why must government intervene ?

As John puts it, there are different types of goods: public and private. Public goods are non-rival and non-excludable products that we all require, such as law and order and street lighting. Government must provide them because the market will not.

Private goods are rival and excludable, have their own allocative mechanism (the market’s invisible hand, as Adam Smith described it), and require minimal government intervention.

John goes on to distinguish between merit goods, which have significant external benefits to society, examples being health and education, and demerit goods, which have significant external social costs, examples being tobacco and alcohol.

How much, then, should government intervene ?

As John sees it, the government mandate should be as follows:

* Buying all the necessary public goods

* Buying State Education – but not interfering in private education

* Buying a Health Service – but not interfering in the provision of private healthcare

* Taxing demerit goods

* Subsidising merit goods

* Balancing their budgets over a three year term (hear ! hear ! from this correspondent)

* Instructing a central bank to target a 2% inflation rate without manipulating interest rates (our preference would be for a target inflation rate of 0%, but then we would favour the abolition of the central bank in the first place).

As a reminder, the current government tax take has not always been this high. Government spending a century ago was only at around 10% of GDP. Government spending as a proportion of national income peaked in 2010 at 44.9%. It will doubtless go higher in the aftermath of the Covid and lockdown insanity.

Not that John is a politician or standing for elected office, but if he were, his manifesto pledges would include the following:

* As much capitalism as possible

* Government to be prohibited from spending more than 20% of national income

* Government to be obliged to balance their budget over a 3 year term, until government spending falls below 20% of national income and the national debt falls below 20% of GDP

* The Bank of England to pursue an inflation target of 2% without recourse to tinkering with interest rates

* A universal basic income to be provided to all adults over the age of 18 through a reverse income tax

* Only those registered as physically or mentally disabled to have access to welfare benefits.

John ends his presentation by asking four (rhetorical) questions:

* Who has ever heard a politician say that they cannot do something ?

* Who would ever vote for a politician who said that they will not do something ?

* Who sees cutting spending and raising interest rates as a way toward faster economic growth ?

* Who sees Brexit as a way of reducing damaging national and international bankruptcy ?

Given the various uncertainties at play, are there ways of hedging your portfolio risk ahead of the next General Election (assuming we are permitted the luxury of one) ?

The answer depends, of course, on the current composition of your portfolio. If it largely resembles our core discretionary offering, either by asset allocation or by way of its underlying components, we would argue that the hedging has already largely been done.

The key risks, as always, remain in the world of debt. An election campaign in which spending intentions have risen across the board by all major parties is not one conducive to the continued stability of either the bond or currency markets. Longstanding readers and clients will appreciate that we loathe bonds in any case, and that the only rationale for holding even short term Gilts, or an ETF exposed to them, is to mitigate bank counterparty risk for large depositors.

So decently yielding defensive stocks are far superior, in our view, to any form of bond, notwithstanding the inevitable price volatility that will accompany them.

Now would not be the time to abandon portfolio protection, whether in the form of absolute return funds (especially our favourites, systematic trend-following funds) or in the form of precious metals investments. The continued relevance of both these types of portfolio hedges is underpinned by the current deterioration in the global geopolitical and economic outlook. In other words, they’re not just offering the prospect of protection against a British political shock, but against a global economic downturn, against a messy inflationary outcome, and much else besides.

On the topic of portfolio protection, we recommend this piece by fund manager Christian Billinger, Some thoughts on downside protection in investing. We would particularly highlight the following observations:

“Like most significant ideas we have adopted as part of our process, this is based on various adaptations of thinking around downside protection by investing greats, including Warren Buffett (“rule number one, never lose money; rule number two, don’t forget rule number one”), Charlie Munger (“invert, always invert”), Mohnish Pabrai (“worry about the downside, the upside will take care of itself”), George Soros (describing his big bet against sterling as low-risk despite the significant amounts of money and high leverage involved), as well as thinkers like Karl Popper (the scientific method and the concept of falsification) and Nassim Taleb (“via negativa”, etc)..

“Essentially, we start out by looking for flaws in any potential investment case and, only once we have failed to detect any obvious issues, will we move on to considering the upside potential. What we really want to find in an investment is limited downside and unlimited or at least very significant upside..

“Looking at the world around us and evolutionary processes, there is also another key argument for applying this kind of thinking, which has to do with survival. For anyone looking to compound capital over a long period of time, the number one consideration has to be to stay in the game by not blowing up. Much of modern portfolio theory is based on thinking around cross-sectional returns (e.g., the average return for fifty money managers during a year) rather than time series returns (e.g., the average return for one money manager over fifty years). It is all very well to say that equities return say 10% annually on average or as an aggregate but this is only relevant for those investors that have managed not to blow up. The average number is not relevant for a time series that includes a zero (i.e., a blowup) anywhere along the way.

“There is also the fact that our ability to forecast anything to do with meaningful drivers of equity returns is limited at best. Our solution at Billinger Förvaltning to this problem has not been to attempt to improve our forecasting but rather to limit our exposure to any forecasting errors through a number of measures outlined below, all with the ultimate aim of creating redundancy in our investment process and its resulting portfolios.

“Aspects of downside protection include:

“Security selection

“First, we have chosen to invest in the equity part of the capital structure as we find the asymmetry between downside and upside appealing.

“What we then effectively do is to invert the investment problem i.e. how do I lose money on this investment? We can then figure out ways of hopefully avoiding such losses. The idea here is that not losing money is the best way of making money. For instance, if I think up a business that would be likely to result in losses over the long term, I would probably imagine a business with no moat or real competitive advantage (e.g. selling a commodity product), highly cyclical revenues, a significant fixed cost base (which in combination with volatile revenues will result in periodic losses), high financial gearing (which together with the above increases the likelihood that we will end up in financial distress), lack of liquidity in the shares (so that we are unable to exit the position without incurring significant losses), etc.

“When we have identified businesses within our circle of competence, we can apply the above inverted thinking and analyse these businesses through several lenses to try and make sure that they are robust by displaying the opposite characteristics, e.g.:

- Revenues (we look for diversified revenue streams, recurring revenues, limited cyclicality, low exposure to potential technology disruption, etc)

- Cost structure (we look for flexibility/limited operating leverage)

- Balance sheet (we look for strong balance sheets, limited complexity in terms of the capital structure, etc)

- Governance (long-term owners, often in the form of families, tend to focus on the survival of the business; their primary focus is preserving the business for their children and beyond)

“In addition, we want the companies we invest in to be time-tested with long track records across different types of environments, etc. The reason for this is that regardless of the amount of work and analysis we perform on a business, time is a much better arbiter of its ultimate durability, often through filters that are not visible to us as investors. This is a case of what Charlie Munger would probably refer to as “looking at what works and what doesn’t, and why”. I also come to think of Terry Smith of Fundsmith who often likes to say that, “we are not trying to pick the next winner, we are looking for businesses that have already won”..

“Some examples of businesses that we feel meet many of the criteria listed above would be found in consumer goods (e.g., beverages, luxury goods), engineering (e.g., elevators and escalators), TIC (testing, inspection, and certification), and real estate.

“Portfolio construction

“Once we have identified suitable securities, we combine them into a portfolio. No matter how much work we do, there will always be unknowns and factors beyond our control. We try to manage this exposure by some diversification. This needs to be balanced against the risk of excessive diversification with the potential for dilution of our best ideas, difficulties in keeping on top of all of our portfolio holdings, etc. In our case, this means holding around twenty positions at any time across different industries and geographies.

“Beyond diversification, we also want most of our holdings to be relatively liquid. This gives us a “right to change our mind”, whether because our analysis was wrong or because new facts emerge.

“At the portfolio level, we want to maintain financial flexibility, which means avoiding leverage as much as possible.

“In terms of position sizing, we like to build positions over time as we get to know a business better and as its track record builds. I like the way the great Tom Gayner describes the gradualism that is practised at Markel by the expression ‘crawl, walk, run’; this is what we aim to emulate.

“Conclusion

“Investing, especially in equities, inevitably exposes us to uncertainty. While the approach I have described will not allow us to avoid mistakes and losses, it does seem to offer us a reasonable chance of growing our capital in real terms over the long run with limited risk of ruin..

“What we are really trying to achieve is to avoid being ‘obviously stupid’ rather than trying to be smart. We are not ignoring the potential upside of an investment but want to do everything we can to limit the downside first..

“Looking at all the above aspects and more, we are trying to add layer after layer of redundancy to “build a fortress” that will last a long time. Being in the game a long time really matters in investing.

“I do identify with how Tom Russo describes his investment approach, which is that of a farmer rather than a hunter. This idea of slow, gradual accumulation suits us well. Over a long enough period of time, we are hopeful this will result in rich harvests.”

Much of Christian’s thinking chimes with our own. Diversify sensibly. Commit to the long run. Most importantly, the best offence is a strong defence. Focus on the downside and the upside should take care of itself. It’s all about staying in the game.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

The most expensive purchase you will ever make ? It is not, as you might think, your home. Nor is it your car, or your children’s or grandchildren’s education. It is not healthcare, though it may, in part, be some of these things.

The most expensive purchase you will ever make is your government.

As Dominic Frisby points out in his excellent book on the history of tax, Daylight Robbery,

“For a typical British middle-class professional over the course of his or her life, the [government tax] bill totals £3.6 million ($5 million) – considerably more than the typical house. You will spend a full 20 years of your life or more in obligatory service to the state. On a time basis, the state owns as much of your labour as the feudal lord did that of the medieval serf, who gave half his working week to farm the land of his lord in exchange for his protection. In exchange, you receive the protection of the state and its services: defence, healthcare, education and so on, for yourself and others. Some people are content with today’s arrangement, others are not, but whatever your political leanings, you have no choice. If you want to work for a living, you must work for the state as well as yourself. We are not as free as we may think we are.”

It was not always so. As the economist John Hearn, who teaches at the London Institute of Banking and Finance, points out, at the beginning of the 20th Century, the UK government was spending about 10% of the nation’s income. But then came the First World War, and the trend has been upwards ever since. As John also points out, not only is government spending in the UK now at or above 50% of national income, but perhaps more alarmingly, there is no real difference in spending plans between each of the major political parties. Whether you support the Conservatives, Labour or the Lib Dems, the age of supposed austerity is well and truly over, as politicians scramble to bribe us all with our own money.

Source: The London Institute of Banking and Finance / John Hearn.

John’s preference for government spending is shown in his chart above (denoted as ‘JBH’), at somewhere less than 25% of UK GDP. Ours, too. Why not zero ? Because there are certain things that only government can provide – things like street lighting and national defence, because the market either can’t or won’t provide them itself.

John goes on to ask: does the economy even need politics or politicians ? Unfortunately, the answer is a reluctant ‘yes’. To understand why, we first need to examine the difference between the profit motive and the vote motive.

Businesses respond to the profit motive. The profit motive and an unconstrained free market create efficiency. In September 1989, Boris Yeltsin, newly elected to the Soviet parliament and the Supreme Soviet, visited the Johnson Space Centre in Houston, Texas. He was probably impressed by what he saw there. He then went on an impromptu visit to a Randall’s supermarket. That was when his eyes really nearly popped out of his skull. As he toured aisles overflowing with goods and produce, he told his entourage that if the Russian people could see the condition of US supermarkets, “there would be a revolution”. As he later wrote,

“When I saw those shelves crammed with hundreds, thousands of cans, cartons and goods of every possible sort, for the first time I felt quite frankly sick with despair for the Soviet people. That such a potentially super-rich country as ours has been brought to a state of such poverty! It is terrible to think of it.”

Within two months, the Berlin Wall had started to come down.

Politicians, on the other hand, are guided primarily by the vote motive – the requirement to be thinking in almost constant terms of re-election. Inasmuch as there is any long term perspective for a politician or MP, it is driven by the electoral cycle.

The vote motive creates inefficiency.

So why must government intervene ?

As John puts it, there are different types of goods: public and private. Public goods are non-rival and non-excludable products that we all require, such as law and order and street lighting. Government must provide them because the market will not.

Private goods are rival and excludable, have their own allocative mechanism (the market’s invisible hand, as Adam Smith described it), and require minimal government intervention.

John goes on to distinguish between merit goods, which have significant external benefits to society, examples being health and education, and demerit goods, which have significant external social costs, examples being tobacco and alcohol.

How much, then, should government intervene ?

As John sees it, the government mandate should be as follows:

* Buying all the necessary public goods

* Buying State Education – but not interfering in private education

* Buying a Health Service – but not interfering in the provision of private healthcare

* Taxing demerit goods

* Subsidising merit goods

* Balancing their budgets over a three year term (hear ! hear ! from this correspondent)

* Instructing a central bank to target a 2% inflation rate without manipulating interest rates (our preference would be for a target inflation rate of 0%, but then we would favour the abolition of the central bank in the first place).

As a reminder, the current government tax take has not always been this high. Government spending a century ago was only at around 10% of GDP. Government spending as a proportion of national income peaked in 2010 at 44.9%. It will doubtless go higher in the aftermath of the Covid and lockdown insanity.

Not that John is a politician or standing for elected office, but if he were, his manifesto pledges would include the following:

* As much capitalism as possible

* Government to be prohibited from spending more than 20% of national income

* Government to be obliged to balance their budget over a 3 year term, until government spending falls below 20% of national income and the national debt falls below 20% of GDP

* The Bank of England to pursue an inflation target of 2% without recourse to tinkering with interest rates

* A universal basic income to be provided to all adults over the age of 18 through a reverse income tax

* Only those registered as physically or mentally disabled to have access to welfare benefits.

John ends his presentation by asking four (rhetorical) questions:

* Who has ever heard a politician say that they cannot do something ?

* Who would ever vote for a politician who said that they will not do something ?

* Who sees cutting spending and raising interest rates as a way toward faster economic growth ?

* Who sees Brexit as a way of reducing damaging national and international bankruptcy ?

Given the various uncertainties at play, are there ways of hedging your portfolio risk ahead of the next General Election (assuming we are permitted the luxury of one) ?

The answer depends, of course, on the current composition of your portfolio. If it largely resembles our core discretionary offering, either by asset allocation or by way of its underlying components, we would argue that the hedging has already largely been done.

The key risks, as always, remain in the world of debt. An election campaign in which spending intentions have risen across the board by all major parties is not one conducive to the continued stability of either the bond or currency markets. Longstanding readers and clients will appreciate that we loathe bonds in any case, and that the only rationale for holding even short term Gilts, or an ETF exposed to them, is to mitigate bank counterparty risk for large depositors.

So decently yielding defensive stocks are far superior, in our view, to any form of bond, notwithstanding the inevitable price volatility that will accompany them.

Now would not be the time to abandon portfolio protection, whether in the form of absolute return funds (especially our favourites, systematic trend-following funds) or in the form of precious metals investments. The continued relevance of both these types of portfolio hedges is underpinned by the current deterioration in the global geopolitical and economic outlook. In other words, they’re not just offering the prospect of protection against a British political shock, but against a global economic downturn, against a messy inflationary outcome, and much else besides.

On the topic of portfolio protection, we recommend this piece by fund manager Christian Billinger, Some thoughts on downside protection in investing. We would particularly highlight the following observations:

“Like most significant ideas we have adopted as part of our process, this is based on various adaptations of thinking around downside protection by investing greats, including Warren Buffett (“rule number one, never lose money; rule number two, don’t forget rule number one”), Charlie Munger (“invert, always invert”), Mohnish Pabrai (“worry about the downside, the upside will take care of itself”), George Soros (describing his big bet against sterling as low-risk despite the significant amounts of money and high leverage involved), as well as thinkers like Karl Popper (the scientific method and the concept of falsification) and Nassim Taleb (“via negativa”, etc)..

“Essentially, we start out by looking for flaws in any potential investment case and, only once we have failed to detect any obvious issues, will we move on to considering the upside potential. What we really want to find in an investment is limited downside and unlimited or at least very significant upside..

“Looking at the world around us and evolutionary processes, there is also another key argument for applying this kind of thinking, which has to do with survival. For anyone looking to compound capital over a long period of time, the number one consideration has to be to stay in the game by not blowing up. Much of modern portfolio theory is based on thinking around cross-sectional returns (e.g., the average return for fifty money managers during a year) rather than time series returns (e.g., the average return for one money manager over fifty years). It is all very well to say that equities return say 10% annually on average or as an aggregate but this is only relevant for those investors that have managed not to blow up. The average number is not relevant for a time series that includes a zero (i.e., a blowup) anywhere along the way.

“There is also the fact that our ability to forecast anything to do with meaningful drivers of equity returns is limited at best. Our solution at Billinger Förvaltning to this problem has not been to attempt to improve our forecasting but rather to limit our exposure to any forecasting errors through a number of measures outlined below, all with the ultimate aim of creating redundancy in our investment process and its resulting portfolios.

“Aspects of downside protection include:

“Security selection

“First, we have chosen to invest in the equity part of the capital structure as we find the asymmetry between downside and upside appealing.

“What we then effectively do is to invert the investment problem i.e. how do I lose money on this investment? We can then figure out ways of hopefully avoiding such losses. The idea here is that not losing money is the best way of making money. For instance, if I think up a business that would be likely to result in losses over the long term, I would probably imagine a business with no moat or real competitive advantage (e.g. selling a commodity product), highly cyclical revenues, a significant fixed cost base (which in combination with volatile revenues will result in periodic losses), high financial gearing (which together with the above increases the likelihood that we will end up in financial distress), lack of liquidity in the shares (so that we are unable to exit the position without incurring significant losses), etc.

“When we have identified businesses within our circle of competence, we can apply the above inverted thinking and analyse these businesses through several lenses to try and make sure that they are robust by displaying the opposite characteristics, e.g.:

“In addition, we want the companies we invest in to be time-tested with long track records across different types of environments, etc. The reason for this is that regardless of the amount of work and analysis we perform on a business, time is a much better arbiter of its ultimate durability, often through filters that are not visible to us as investors. This is a case of what Charlie Munger would probably refer to as “looking at what works and what doesn’t, and why”. I also come to think of Terry Smith of Fundsmith who often likes to say that, “we are not trying to pick the next winner, we are looking for businesses that have already won”..

“Some examples of businesses that we feel meet many of the criteria listed above would be found in consumer goods (e.g., beverages, luxury goods), engineering (e.g., elevators and escalators), TIC (testing, inspection, and certification), and real estate.

“Portfolio construction

“Once we have identified suitable securities, we combine them into a portfolio. No matter how much work we do, there will always be unknowns and factors beyond our control. We try to manage this exposure by some diversification. This needs to be balanced against the risk of excessive diversification with the potential for dilution of our best ideas, difficulties in keeping on top of all of our portfolio holdings, etc. In our case, this means holding around twenty positions at any time across different industries and geographies.

“Beyond diversification, we also want most of our holdings to be relatively liquid. This gives us a “right to change our mind”, whether because our analysis was wrong or because new facts emerge.

“At the portfolio level, we want to maintain financial flexibility, which means avoiding leverage as much as possible.

“In terms of position sizing, we like to build positions over time as we get to know a business better and as its track record builds. I like the way the great Tom Gayner describes the gradualism that is practised at Markel by the expression ‘crawl, walk, run’; this is what we aim to emulate.

“Conclusion

“Investing, especially in equities, inevitably exposes us to uncertainty. While the approach I have described will not allow us to avoid mistakes and losses, it does seem to offer us a reasonable chance of growing our capital in real terms over the long run with limited risk of ruin..

“What we are really trying to achieve is to avoid being ‘obviously stupid’ rather than trying to be smart. We are not ignoring the potential upside of an investment but want to do everything we can to limit the downside first..

“Looking at all the above aspects and more, we are trying to add layer after layer of redundancy to “build a fortress” that will last a long time. Being in the game a long time really matters in investing.

“I do identify with how Tom Russo describes his investment approach, which is that of a farmer rather than a hunter. This idea of slow, gradual accumulation suits us well. Over a long enough period of time, we are hopeful this will result in rich harvests.”

Much of Christian’s thinking chimes with our own. Diversify sensibly. Commit to the long run. Most importantly, the best offence is a strong defence. Focus on the downside and the upside should take care of itself. It’s all about staying in the game.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price