“Christian Szell: Is it safe?… Is it safe?

Babe: You’re talking to me?

Christian Szell: Is it safe?

Babe: Is what safe?

Christian Szell : Is it safe?

Babe: I don’t know what you mean. I can’t tell you something’s safe or not, unless I know specifically what you’re talking about.

Christian Szell: Is it safe?

Babe: Tell me what the “it” refers to.

Christian Szell: Is it safe?

Babe: Yes, it’s safe, it’s very safe, it’s so safe you wouldn’t believe it.

Christian Szell: Is it safe?

Babe: No. It’s not safe, it’s… very dangerous, be careful.”

- Laurence Olivier and Dustin Hoffman, ‘Marathon Man’, dir. John Schlesinger, 1976.

“With 52 trading days remaining in this unprosperous year, bond markets are registering their worst returns in the history of the English-speaking peoples. We write to elaborate on this striking fact, not forgetting the quality of the money in which the bonds are denominated or the lengths to which the stewards of that scrip have gone to suppress the rates of interest they control (or used to control), or the maelstrom of derivatives with which professional investors had hoped to protect themselves against the policies of the central bankers, one of whom, on Monday, was presented with one-third of the 2022 Nobel Memorial Prize in “economic ‘sciences’.”

“The lurch higher in yields is no ordinary upheaval. Ten basis points a year was the tempo of the rise in long yields during the first decade of the only two bear bond markets in the past 100- plus years: the cycles of 1900–20 and 1946–81. In the past 12 months, 10- year Treasury yields have climbed by almost 150 basis points.

“To meet devouring margin calls, British and continental financial institutions, awkwardly hedged against the risk of falling interest rates, have dumped bonds, the British institutions, into the lap of the Bank of England. How did they get themselves into such a pickle? In the first place, by living in the era of QE, fiat currencies and financial repression. In the second, by making the acquaintance of a derivatives salesman. “It’s like trying to explain some aspects of quantum physics to people who aren’t really physicists,” one such vendor of leveraged strategies intended to deliver income in the absence of normal interest rates was quoted as complaining in last weekend’s Financial Times.”

- Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, ‘The Stocks look pale’, 14th October 2022.

From ‘Investing through the Looking Glass’ (this correspondent), published by Harriman House, 2016:

“Where’s the inflation ?

“It is certainly staggering that even after expanding its balance sheet by $3.5 trillion, the Fed has been unable to trigger visible price inflation in anything other than financial assets. One dreads to contemplate the scale of the altogether less visible private sector deleveraging that has cancelled it out. One notes that while bonds are behaving precisely in line with the Ice Age thesis, stock markets – by and large – are not quite following the plot.

“Of course, if interest rates squat at zero or lower, and bonds are expensive, then investors will inevitably chase income and returns in a more attractive-seeming market – namely that for listed stocks. The by-product of these malign trends is that it makes rational investment and asset allocation, and more narrowly the pursuit of real capital preservation, almost impossible.

“The inability of bond yields to reflect the gargantuan and still surging supply of government debt is a clear example of market failure brought about by institutional fund managers and the consultants that guide their institutional investor clients. There is simply no punishment for ill-disciplined government borrowers.

“To put it another way, where have the bond vigilantes gone ?

“It is not as if politicians asleep at the wheel have gone entirely unnoticed. Several high-profile reports have recently been published drawing attention to the debt problems gnawing away at the economic vitality of the West. Perhaps the most damning response to date has come from the euro zone’s pre-eminent political cynic, Jean-Claude Juncker: “We all know what to do, we just don’t know how to get re-elected after we’ve done it.”

“This may be the most dangerous market environment in history.

“Investors have placed a lot of faith in the ability of central banks to avoid disaster – to suppress market interest rates and bond yields, and to support equity prices. But as the Swiss National Bank showed in January 2015 when it removed the Swiss franc’s peg to the euro, central banks cannot always be trusted. Investors – both in stocks and in bonds – are effectively playing chicken with the central banks, surfing a tidal wave of liquidity on the expectation that this liquidity, an ocean of easy money, will never drain away. Who will blink first: markets or central banks ?

“The financial markets are awkwardly polarised between fears of profound debt deflation and fears of uncomfortable monetary inflation. On the basis that generals are invariably transfixed by the last war, it might be fair to suggest that Americans are determined never again to experience the debt deflation of the 1930s. Given the role and extent of government indebtedness throughout the modern world, a debt deflation is a practically unthinkable outcome. But just because something is deeply undesirable does not make it impossible. In their eagerness to pump money into the system to make up for the credit contraction caused by an ailing banking system, the politicians of today may be setting themselves up for the last financial war painfully recalled by German monetary officials, namely the Weimar hyperinflation.

“If officials don’t deliberately design or ignite an inflation, it may come about in any case via the foreign exchange markets, or a surge in government bond yields.

“As Jens Parsson indicates in his study Dying of Money: “The spectre that waits in the wings of any inflation, including the American, is the general exodus of the people from the currency when they lose faith in it at last. When this spectre steps in from the wings, the government’s games are over and the final curtain is not far away.”

“The practical response to overvaluation in the bond market?

“If you do not need to own bonds, then don’t. And if you are obligated to hold bond investments for some reason, then focus solely on high-quality bonds issued by creditor countries or issuers as opposed to debtors.

“Central banks may have succeeded in supporting bond prices, and suppressing bond yields, by way of outrageous price manipulation, but history suggests they will not be able to do so forever. At some point, the market will have its say. Its response is likely to be unprintable for the holders of most forms of government debt.

“In the meantime, superior investment choices exist. Investors requiring any combination of income and capital growth will almost certainly be better off purchasing the shares of high-quality businesses at fair valuations instead.

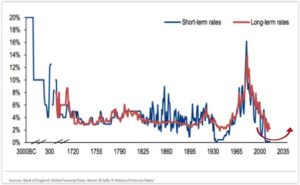

Short and long-term interest rates, 3000 BC to today

“(For data prior to the 18th century, the Bank has used interest rates reflecting the country with the lowest interest rate reported for various types of credit. From 3,000 BC to the 6th century BC these rates come from the Babylonian Empire. From the 6th century BC to the 2nd century BC they come from Greece. From the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD they are drawn from the Roman Empire. Subsequent data come from regions including the Netherlands and Italy. This is a credible history of global interest rates.)

“And those rates haven’t been lower in 5000 years. For anyone alive during that 1970s inflationary spike in interest rates, the interest rate game has clearly changed profoundly within their own lifetimes.

“When interest rates sit as such derisory levels, the implications for investors are not exactly promising. All things being equal, the likely returns from stock markets have to be seen in the context of the likely returns from bond markets. And since a third of the sovereign bond market now trades at a negative yield, investors in the stock market should manage their expectations carefully.

“Although the timing is not clear, at some point interest rates must rise – unless our central banks can keep them at or below zero indefinitely. In the event that interest rates rise – and in a somewhat uncontrolled, involuntary way – the damage to bond markets could be spectacular.”

- From ‘Investing through the Looking Glass’, published by Harriman House, 2016.

Words always matter, but in an unhinged financial landscape such as today’s, they take on unusual significance. How to define ‘safety’ without reference to what ‘risk’ denotes ? Financial service providers do their clients a disservice by simplistically equating risk with volatility, for example. Real risk is working your whole career for Lehman Brothers and having your life savings in Lehman Brothers stock. Then September 2008 happens and you have no job – and no life savings. Real risk is a catastrophic loss of capital from which there can be no possible recovery.

‘Investing through the Looking Glass’ was written by this correspondent six years ago. How did it conclude ?

“Investing when the game changes

“As investors, we live in extraordinary times. Quantitative easing is not normal. Government bonds of heavily indebted countries trading at negative yields is not normal. Negative interest rates are not normal. Deflation in the modern world is not normal. But we are faced with all of them.

“What is the prudent investor to do ?

“Forty-four years after the end of the Bretton Woods system, central banks are close to the limit of what is possible within the realm of monetary policy. What once seemed unthinkable – negative yields on sovereign bonds and negative deposit rates from commercial banks – is now commonplace. Weird acronyms – like ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy), NIRP (Negative Interest Rate Policy), QQE (Qualitative and Quantitative Easing) – are everywhere. Investors throughout the world are struggling to find safe assets whose prices haven’t been hopelessly distorted by a tidal wave of easy money seeking a quick return. Savers struggle in vain to find attractive yields at low risk.

“And financial markets are now conditioned to expect central banks to respond to crises of virtually any kind with aggressive monetary stimulus. In the first few months of 2016, 49 central banks cut rates or devalued their currencies in pursuit of competitive advantage versus their peers (clearly not everyone can devalue at the same time). Since 2008 there have been over 600 interest rate cuts worldwide. Globally we have printed the equivalent of $14 trillion. And still much of the global economy, including many of the world’s emerging markets, is slowing.

“The harsh reality is that nobody can possibly say with any certainty how the current financial landscape will evolve over the months and years to come. Now that bond yields and interest rates have pierced the theoretical lower bound of zero, all bets are off. Fully one-third of the entire sovereign bond market now trades with a negative yield. With the QE genie well and truly out of the bottle, nobody can say what the future path of interest rates will look like.

“I don’t pretend that the investment outlook is exactly rosy, but as savers and investors we all have to operate in the world as it is, not as we might wish it to be. In this book I have identified what I believe to be the primary factors and some of the more delusional thinking that has led to our current financial crisis. But I have also presented some of the solutions that pragmatic investors can use to shepherd their sacred assets through whatever storms may come. We clearly live in interesting times. I wish you well in the interesting times to come.”

Six years ago, we believed that classic defensive ‘value’ stocks, systematic trend-following funds, and a healthy allocation to precious metals and ‘value’ commodities stocks were the answer to ‘interesting times’. We believed so then, and we still believe so today.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

“Christian Szell: Is it safe?… Is it safe?

Babe: You’re talking to me?

Christian Szell: Is it safe?

Babe: Is what safe?

Christian Szell : Is it safe?

Babe: I don’t know what you mean. I can’t tell you something’s safe or not, unless I know specifically what you’re talking about.

Christian Szell: Is it safe?

Babe: Tell me what the “it” refers to.

Christian Szell: Is it safe?

Babe: Yes, it’s safe, it’s very safe, it’s so safe you wouldn’t believe it.

Christian Szell: Is it safe?

Babe: No. It’s not safe, it’s… very dangerous, be careful.”

“With 52 trading days remaining in this unprosperous year, bond markets are registering their worst returns in the history of the English-speaking peoples. We write to elaborate on this striking fact, not forgetting the quality of the money in which the bonds are denominated or the lengths to which the stewards of that scrip have gone to suppress the rates of interest they control (or used to control), or the maelstrom of derivatives with which professional investors had hoped to protect themselves against the policies of the central bankers, one of whom, on Monday, was presented with one-third of the 2022 Nobel Memorial Prize in “economic ‘sciences’.”

“The lurch higher in yields is no ordinary upheaval. Ten basis points a year was the tempo of the rise in long yields during the first decade of the only two bear bond markets in the past 100- plus years: the cycles of 1900–20 and 1946–81. In the past 12 months, 10- year Treasury yields have climbed by almost 150 basis points.

“To meet devouring margin calls, British and continental financial institutions, awkwardly hedged against the risk of falling interest rates, have dumped bonds, the British institutions, into the lap of the Bank of England. How did they get themselves into such a pickle? In the first place, by living in the era of QE, fiat currencies and financial repression. In the second, by making the acquaintance of a derivatives salesman. “It’s like trying to explain some aspects of quantum physics to people who aren’t really physicists,” one such vendor of leveraged strategies intended to deliver income in the absence of normal interest rates was quoted as complaining in last weekend’s Financial Times.”

From ‘Investing through the Looking Glass’ (this correspondent), published by Harriman House, 2016:

“Where’s the inflation ?

“It is certainly staggering that even after expanding its balance sheet by $3.5 trillion, the Fed has been unable to trigger visible price inflation in anything other than financial assets. One dreads to contemplate the scale of the altogether less visible private sector deleveraging that has cancelled it out. One notes that while bonds are behaving precisely in line with the Ice Age thesis, stock markets – by and large – are not quite following the plot.

“Of course, if interest rates squat at zero or lower, and bonds are expensive, then investors will inevitably chase income and returns in a more attractive-seeming market – namely that for listed stocks. The by-product of these malign trends is that it makes rational investment and asset allocation, and more narrowly the pursuit of real capital preservation, almost impossible.

“The inability of bond yields to reflect the gargantuan and still surging supply of government debt is a clear example of market failure brought about by institutional fund managers and the consultants that guide their institutional investor clients. There is simply no punishment for ill-disciplined government borrowers.

“To put it another way, where have the bond vigilantes gone ?

“It is not as if politicians asleep at the wheel have gone entirely unnoticed. Several high-profile reports have recently been published drawing attention to the debt problems gnawing away at the economic vitality of the West. Perhaps the most damning response to date has come from the euro zone’s pre-eminent political cynic, Jean-Claude Juncker: “We all know what to do, we just don’t know how to get re-elected after we’ve done it.”

“This may be the most dangerous market environment in history.

“Investors have placed a lot of faith in the ability of central banks to avoid disaster – to suppress market interest rates and bond yields, and to support equity prices. But as the Swiss National Bank showed in January 2015 when it removed the Swiss franc’s peg to the euro, central banks cannot always be trusted. Investors – both in stocks and in bonds – are effectively playing chicken with the central banks, surfing a tidal wave of liquidity on the expectation that this liquidity, an ocean of easy money, will never drain away. Who will blink first: markets or central banks ?

“The financial markets are awkwardly polarised between fears of profound debt deflation and fears of uncomfortable monetary inflation. On the basis that generals are invariably transfixed by the last war, it might be fair to suggest that Americans are determined never again to experience the debt deflation of the 1930s. Given the role and extent of government indebtedness throughout the modern world, a debt deflation is a practically unthinkable outcome. But just because something is deeply undesirable does not make it impossible. In their eagerness to pump money into the system to make up for the credit contraction caused by an ailing banking system, the politicians of today may be setting themselves up for the last financial war painfully recalled by German monetary officials, namely the Weimar hyperinflation.

“If officials don’t deliberately design or ignite an inflation, it may come about in any case via the foreign exchange markets, or a surge in government bond yields.

“As Jens Parsson indicates in his study Dying of Money: “The spectre that waits in the wings of any inflation, including the American, is the general exodus of the people from the currency when they lose faith in it at last. When this spectre steps in from the wings, the government’s games are over and the final curtain is not far away.”

“The practical response to overvaluation in the bond market?

“If you do not need to own bonds, then don’t. And if you are obligated to hold bond investments for some reason, then focus solely on high-quality bonds issued by creditor countries or issuers as opposed to debtors.

“Central banks may have succeeded in supporting bond prices, and suppressing bond yields, by way of outrageous price manipulation, but history suggests they will not be able to do so forever. At some point, the market will have its say. Its response is likely to be unprintable for the holders of most forms of government debt.

“In the meantime, superior investment choices exist. Investors requiring any combination of income and capital growth will almost certainly be better off purchasing the shares of high-quality businesses at fair valuations instead.

Short and long-term interest rates, 3000 BC to today

“(For data prior to the 18th century, the Bank has used interest rates reflecting the country with the lowest interest rate reported for various types of credit. From 3,000 BC to the 6th century BC these rates come from the Babylonian Empire. From the 6th century BC to the 2nd century BC they come from Greece. From the 2nd century BC to the 5th century AD they are drawn from the Roman Empire. Subsequent data come from regions including the Netherlands and Italy. This is a credible history of global interest rates.)

“And those rates haven’t been lower in 5000 years. For anyone alive during that 1970s inflationary spike in interest rates, the interest rate game has clearly changed profoundly within their own lifetimes.

“When interest rates sit as such derisory levels, the implications for investors are not exactly promising. All things being equal, the likely returns from stock markets have to be seen in the context of the likely returns from bond markets. And since a third of the sovereign bond market now trades at a negative yield, investors in the stock market should manage their expectations carefully.

“Although the timing is not clear, at some point interest rates must rise – unless our central banks can keep them at or below zero indefinitely. In the event that interest rates rise – and in a somewhat uncontrolled, involuntary way – the damage to bond markets could be spectacular.”

Words always matter, but in an unhinged financial landscape such as today’s, they take on unusual significance. How to define ‘safety’ without reference to what ‘risk’ denotes ? Financial service providers do their clients a disservice by simplistically equating risk with volatility, for example. Real risk is working your whole career for Lehman Brothers and having your life savings in Lehman Brothers stock. Then September 2008 happens and you have no job – and no life savings. Real risk is a catastrophic loss of capital from which there can be no possible recovery.

‘Investing through the Looking Glass’ was written by this correspondent six years ago. How did it conclude ?

“Investing when the game changes

“As investors, we live in extraordinary times. Quantitative easing is not normal. Government bonds of heavily indebted countries trading at negative yields is not normal. Negative interest rates are not normal. Deflation in the modern world is not normal. But we are faced with all of them.

“What is the prudent investor to do ?

“Forty-four years after the end of the Bretton Woods system, central banks are close to the limit of what is possible within the realm of monetary policy. What once seemed unthinkable – negative yields on sovereign bonds and negative deposit rates from commercial banks – is now commonplace. Weird acronyms – like ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy), NIRP (Negative Interest Rate Policy), QQE (Qualitative and Quantitative Easing) – are everywhere. Investors throughout the world are struggling to find safe assets whose prices haven’t been hopelessly distorted by a tidal wave of easy money seeking a quick return. Savers struggle in vain to find attractive yields at low risk.

“And financial markets are now conditioned to expect central banks to respond to crises of virtually any kind with aggressive monetary stimulus. In the first few months of 2016, 49 central banks cut rates or devalued their currencies in pursuit of competitive advantage versus their peers (clearly not everyone can devalue at the same time). Since 2008 there have been over 600 interest rate cuts worldwide. Globally we have printed the equivalent of $14 trillion. And still much of the global economy, including many of the world’s emerging markets, is slowing.

“The harsh reality is that nobody can possibly say with any certainty how the current financial landscape will evolve over the months and years to come. Now that bond yields and interest rates have pierced the theoretical lower bound of zero, all bets are off. Fully one-third of the entire sovereign bond market now trades with a negative yield. With the QE genie well and truly out of the bottle, nobody can say what the future path of interest rates will look like.

“I don’t pretend that the investment outlook is exactly rosy, but as savers and investors we all have to operate in the world as it is, not as we might wish it to be. In this book I have identified what I believe to be the primary factors and some of the more delusional thinking that has led to our current financial crisis. But I have also presented some of the solutions that pragmatic investors can use to shepherd their sacred assets through whatever storms may come. We clearly live in interesting times. I wish you well in the interesting times to come.”

Six years ago, we believed that classic defensive ‘value’ stocks, systematic trend-following funds, and a healthy allocation to precious metals and ‘value’ commodities stocks were the answer to ‘interesting times’. We believed so then, and we still believe so today.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price