On October 30, 1935, the US Army Air Corps held a flight competition at Wright Air Field in Dayton, Ohio. The contest was conducted for manufacturers hoping to secure the contract for the army’s next-generation long-range bomber.

It was likely to be a one-horse race. Boeing’s dazzling aluminium-alloy Model 299, in earlier tests, had wiped the floor with the competing designs of Martin and Douglas. The Boeing aircraft could carry five times as many bombs as the army had requested. Not only did it fly faster than all previous aircraft, it could fly almost twice as far.

A journalist from Seattle who had watched the plane on a previous test flight over the city christened it the “flying fortress”, and the name stuck. So the competition itself was more or less a formality. The army intended to order at least sixty-five of the aircraft.

A mixed crowd of top brass and manufacturing staff watched the Model 299 test plane taxi onto the runway. Rather than the usual two it possessed four engines, and it had a 103-foot wingspan.

The plane shot down the tarmac, lifted off without incident and climbed to three hundred feet.

It then stalled, turned on one wing, and crashed into the ground. Two of the five crew died, including the pilot, Major Ployer Peter Hill.

Hill himself was hardly a rookie. He had been the air corps’ chief of flight testing. Few people in the military could have boasted more experience or expertise.

But an investigation concluded that the plane had suffered no mechanical defects. The cause of the crash was “pilot error”.

The Model 299 was significantly more complex than previous aircraft. The new plane required the pilot to monitor each of the four engines, and each engine had its own oil-fuel mix. The pilot also had to attend to the retractable landing gear, the wing flaps, trim tabs to maintain stability at different air speeds, and propellers whose pitch needed to be regulated by means of hydraulic controls.

One newspaper wrote that the Boeing model was “too much airplane for one man to fly”. Douglas’ smaller design was therefore judged to be the winner. Boeing nearly went bankrupt.

The army nevertheless purchased a handful of aircraft from Boeing and some engineers remained convinced that the plane could be flown. A group of test pilots got together and deliberated on the problem.

In the words of Atul Gawande,

“What they decided not to do was almost as interesting as what they actually did.”

They did not require Model 299 pilots to undergo longer training. Instead, they came up with an ingenious solution.

They created a pilot’s checklist.

Aeronautics had come quite a way since the days of the Wright brothers. During the dawn of aviation, getting a plane airborne might have been nerve-racking but it was hardly a complex manoeuvre. Using a checklist during take-off would have seemed absurd. But the new model was too complicated to be left to any single person, no matter how expert.

The test pilots kept their checklist simple and concise. It was short enough to fit on an index card, with step-by-step checks for take-off, flight, landing and taxiing. The checklist ensured that the brakes were released, that instruments were set, that doors and windows were closed – elementary stuff. But with the checklist at hand, pilots went on to fly the Model 299 a total of 1.8 million miles without a single accident. The army went on to order almost 13,000 aircraft, which were named the B-17. Because this giant could now be flown without incident, the US army gained a decisive advantage in the Second World War. The pilots’ checklist arguably changed the course of history.

The chances are, if you speak to any financial adviser, they’ll tell you that asset allocation – how you divide up your investible pot among the major asset classes, including debt, equity, property, commodities and alternative investments – is the single most important investment decision you will make. And they’re almost certainly right to do so.

The financial services industry typically cites a study from 1986 by Gary Brinson, Randolph Hood and Gilbert Beebower (BHB) which examined the asset allocation of 91 large pension funds between 1974 and 1983.

BHB replaced those funds’ specific stock, bond and cash selections with comparable market indices. The quarterly returns of the indexed portfolios were found to be higher than the quarterly returns of the more actively managed portfolios. BHB put a figure on it. The correlation between the two series was measured at 96.7%, with a shared variance of 93.6%.

The study’s effective conclusion was that a simple indexed approach worked just as well as using professional fund managers. A secondary conclusion was that a relatively small number of asset classes was sufficient for the purposes of financial planning. Financial advisers have tended to regard the BHB study as proof that asset allocation is much more important than either security selection or market timing combined.

This conclusion is probably broadly correct. But we still believe in active portfolio management.

Why?

Classical economics teaches us that value is subjective. More to the point, the value in investments is also contextual. It is dependent on the wider financial environment.

Consider exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Many financial advisers swear by them. They cite studies like BHB, and point out, quite correctly, that management fees are crucial in the context of longer term returns.

But in keeping portfolio costs down to their lowest levels, these advisers are being penny-wise and pound-foolish. If a given stock market is dangerously expensive by any rational analysis, there’s no point in maintaining exposure to it using a cheap index-tracking instrument.

The rational response is to try and identify a superior (not least by being demonstrably cheaper) market.

By way of a notorious example, we give you the S&P 500 Index.

Source: https://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe

The chart above shows the history of the S&P 500 equity index as assessed by Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted p/e ratio. This is simply a 10 year smoothed average of p/e ratios, which takes out a lot of the noise generated when using a current constant ratio.

Note that at a current Shiller p/e of 29.6, the US broad equity market stands significantly above its long run average of 17. (The market’s lowest ever Shiller p/e was at 4.8 in December 1920 – a great time to be buying stocks. Its highest ever Shiller p/e was at 44.2 in December 1999 – a dreadful time to be buying stocks.)

Note also the little red dot in 1987 which represents the ’87 Crash. Which now looks like a blip.

Note also that the US stock market, on a Shiller basis, has only really been more expensive than today on a handful of occasions: one of them was in 1929, and one of them was in 1999. Draw your own conclusions.

None of which is to say that we’re predicting a Crash. But we are trying to highlight the fact that the broad US stock markets are expensive today. Anybody buying broad market exposure today faces a future of pretty miserable returns, in our opinion. This isn’t an opinion founded on bearishness, just an assessment based on 130 years of market history.

So given a choice between getting cheap index exposure to the US stock market and looking elsewhere for opportunities altogether, we favour looking elsewhere.

But that’s still looking at the investible universe solely through the prism of listed stocks, and there are clearly other ways we can invest our hard-earned cash.

In his book ‘Fail-safe investing’, the late US investment analyst Harry Browne outlines one of the simplest investment philosophies you will ever find. It would go on to find expression in the 1982 launch of the Permanent Portfolio mutual fund (ticker PRPFX US).

Browne’s ‘Fail-safe’ or ‘bullet-proof’ portfolio is a diversified investment portfolio comprising just four asset classes:

Each of these asset classes should, according to Browne, be held to the order of 25% of your overall investments. Each year, simply rebalance each holding back to 25%. The rationale for this approach is as follows.

Stocks offer you a claim on growth in the real economy. During times of prosperity, it’s reasonable to assume that a broad exposure to stocks will deliver decent returns. Browne advocated the use of a basic S&P 500 index fund. Clearly, we have some misgivings about that particular instrument and index, but we acknowledge the basic approach.

Bonds offer you protection in the event of outright deflation. In a more ‘normal’ and low inflationary economic environment, bonds should also deliver respectable returns. But clearly we are not in a normal environment. Interest rates have – until very recently – been falling for over 40 years.

Very few people in any bond dealing room anywhere on the planet have ever seen a sustained bear market for bonds. So it’s worth bearing in mind that in a rising rate environment, or in a credit shock, bonds will do poorly.

Cash offers you a hedge of sorts in the event of “tight money” or recession. In outright deflation it makes sense to hold cash, provided it’s with a banking institution of sufficient creditworthiness. Don’t forget that the moment you park your money in a bank, legally it is no longer your money, but the bank’s. You become an unsecured creditor of the bank.

Gold should offer you a degree of protection in an environment of high inflation, or financial systemic distress.

It has also existed as a form of sound money for thousands of years, and we see huge merit in holding gold – in the right form – in the context of a global debt crisis and international currency war that shows no signs of being resolved.

Dylan Grice, formerly a strategist at French investment bank SocGen, has written a nice companion piece to Browne’s ‘Failsafe investing’. It was Dylan’s final strategy piece on leaving SocGen, published in November 2012 and titled ‘Cockroaches for the long run!’

Dylan’s thesis goes as follows.

The humble cockroach gets something of a bad press, but it is undoubtedly a survivor.

The oldest cockroach fossil is 350 million years old. Human beings, by way of contrast, have only been around for roughly 50,000 years. And cockroaches survived the third, fourth and fifth global mass extinctions (the last being the Cretaceous period event that did for the dinosaurs).

Cockroaches can go without air for 45 minutes, survive submerged under water for half an hour, and can survive freezing temperatures. They can even withstand 15 times more radiation than humans – so they stand a good chance of surviving a nuclear war.

But they operate according to one of the simplest algorithms in nature. Richard Bookstaber describes it as:

“singularly simple and seemingly suboptimal: it moves in the opposite direction of gusts of wind that might signal an approaching predator.”

That’s it. Simple – but spectacularly robust.

Dylan goes on to ask: if you were going to try and replicate the robustness of a cockroach within an investment portfolio, what might that portfolio look like?

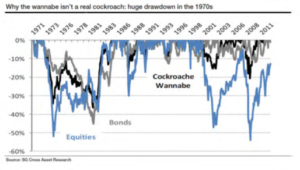

His first stab at creating the robust portfolio is the “cockroach wannabe”: a portfolio consisting of 50% bonds, 50% equities. The problem with the “cockroach wannabe” is that it isn’t really as robust as it sounds. Consider the performance of the “cockroach wannabe” during the 1970s – a decade that saw horrific drawdowns in both bonds and stocks..

As Dylan’s chart above makes clear, although the “cockroach wannabe” fared somewhat better than stocks (in blue in the chart above) – which saw peak to trough losses of over 50% during the mid-70s – it was hardly as resistant to market plunges as its namesake. The selloff in bonds (shown in grey) was almost as gruelling; and the “cockroach wannabe”, shown in black, fared almost as badly as debt investments, and in some instances worse.

So Dylan’s conclusion ends up being very similar to that of Harry Browne.

Dylan’s “cockroach portfolio” would be inflation resistant, deflation resistant, credit inflation resistant, credit deflation resistant… despite having no view on which scenario was more likely at any given point in time.

So the cockroach doesn’t make any outright bets. It puts half of its money into real assets, and the other half into nominal ones. It then divides its nominal and real allocations further, into productive and unproductive assets. It puts 25% of its portfolio into stocks, 25% into gold, 25% into government bonds, and it keeps 25% in the form of cash.

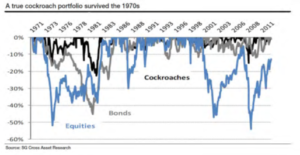

So how does the “true cockroach” portfolio fare versus the wannabe? The chart below reveals all.

The “true cockroach” portfolio – with exactly the same asset mix as Harry Browne’s original Permanent Portfolio – offers some very real protection against the vagaries of an unknown future. Compared with the drawdowns experienced by either stock markets or bonds, the “true cockroach” emerges from market crises more or less completely unscathed.

And over the course of Dylan’s timeline (1971 to 2011) the returns weren’t bad either: 5% real (after-inflation) returns since 1971, compared with 5.5% real returns for equities, and 4% real returns from government bonds.

So if you’re motivated primarily by risk avoidance and capital preservation, there are certainly worse strategies to consider than the Permanent Portfolio / “Cockroach Portfolio” approach.

If we were to distil the Permanent Portfolio philosophy into a checklist, it would look something like this:

- Ensure that if you hold bonds, hold only objectively high quality bonds offering meaningful yields relative to inflation. (This is admittedly easier said than done these days. And having ‘AAA’ or ‘AA’ credit ratings from the likes of Moody’s or Standard & Poor’s does not mean what it used to.) Nevertheless, in a (deflationary) financial crisis, there will probably be some merit in holding even US Treasury bonds, which are hardly the most creditworthy debt instruments in the world.

The reason we say this is that the Yale Endowment, under the supervision of David Swensen, one of the world’s most well respected institutional investors, managed to lose something like 25% of its value between 2007 and 2008. One of the reasons it lost so much money is that it did not have any exposure to the one asset class that would, back then, have preserved its capital.

In fact, the Yale Endowment was outright short US Treasury debt during the period in question.

If they had had meaningful exposure to US Treasuries, they would have recorded decent gains from those holdings. The fail-safe portfolio is blind to the vagaries of the herd. We simply do not know what the future holds.

- Ensure you hold diversified equity exposure. This can clearly be accommodated in a variety of ways. The cost-conscious may favour ETFs. Those with a heightened tolerance for risk may prefer to construct a portfolio of individual stocks, or actively managed specialist funds.

Given that US market valuations currently look stretched, you may well want to consider international markets as well. We see especial value today in commodities stocks, ideally those unencumbered by high levels of debt.

- Ensure you maintain a cash reserve, held with a high quality banking institution.

- Ensure you hold some other form of uncorrelated asset. It is vital that this asset does not simply track, to a greater or lesser extent, the performance of either stocks or bonds. Gold is one example. Systematic trend-following funds are another.

- Ensure that you have a minimum of 10% of your investible asset pot in each of the above asset classes. Anything demonstrably less than 10% means that you don’t really have sufficient genuine diversification.

- Whatever your specific allocation to each asset, which can clearly vary according to situation, time horizon and risk tolerance, ensure that you rebalance your portfolio back to its target weightings at least annually.

That caters to the asset allocation process. If we look more specifically at just the equity portion of a portfolio, our checklist would look something like this:

- Ensure you have at least 15 separate equity holdings, ideally somewhere between 15 and 20. This will equate to an optimal portfolio. A demonstrably lower figure by way of underlying holdings might be unreasonably concentrated. A demonstrably higher figure simply amounts to “diworsification”.

- For each equity holding, ensure it possesses each and all of the following characteristics, namely:

- i) A high quality business with a defensible ‘moat’ around it;

- ii) High quality management, who continually align their interests with those of their shareholders;

iii) The shares are trading at an attractive discount to any objective assessment of their inherent value or, at the very least, are not trading at an uncomfortably high multiple in terms of price / book or price / earnings.

All things equal, a price / book of less than 1.5x is preferred, as is a price / earnings ratio of 15x or less. Having little or no debt is also preferred.

- Ensure that your holdings aren’t dominated by any one industrial sector.

- Remember Warren Buffett’s advice about the punch-card, which may be one of the most powerful metaphors in finance:

“I could improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only twenty slots in it so that you had twenty punches – representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime. And once you’d punched through the card, you couldn’t make any more investments at all. Under those rules, you’d really think carefully about what you did, and you’d be forced to load up on what you’d really thought about. So you’d do so much better.”

- If in doubt, do nothing. Far better than overtrading.

—

We began this week’s letter with a downed plane. Sick people, as Atul Gawande points out in his book ‘The checklist manifesto’, are extraordinarily more various than airplanes. He cites a study of 41,000 trauma patients in the state of Pennsylvania. Those patients had 1,224 different injury-related diagnoses, in 32,261 unique combinations.

“That’s like having 32,261 kinds of airplane to land.”

The solution? Simplify. And, perhaps, incorporate some form of checklist into your own investment process. What works in an airplane or in a hospital stands a good chance of working in your own portfolio. Look at it another way: how many mistakes can you survive ?

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you, too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

On October 30, 1935, the US Army Air Corps held a flight competition at Wright Air Field in Dayton, Ohio. The contest was conducted for manufacturers hoping to secure the contract for the army’s next-generation long-range bomber.

It was likely to be a one-horse race. Boeing’s dazzling aluminium-alloy Model 299, in earlier tests, had wiped the floor with the competing designs of Martin and Douglas. The Boeing aircraft could carry five times as many bombs as the army had requested. Not only did it fly faster than all previous aircraft, it could fly almost twice as far.

A journalist from Seattle who had watched the plane on a previous test flight over the city christened it the “flying fortress”, and the name stuck. So the competition itself was more or less a formality. The army intended to order at least sixty-five of the aircraft.

A mixed crowd of top brass and manufacturing staff watched the Model 299 test plane taxi onto the runway. Rather than the usual two it possessed four engines, and it had a 103-foot wingspan.

The plane shot down the tarmac, lifted off without incident and climbed to three hundred feet.

It then stalled, turned on one wing, and crashed into the ground. Two of the five crew died, including the pilot, Major Ployer Peter Hill.

Hill himself was hardly a rookie. He had been the air corps’ chief of flight testing. Few people in the military could have boasted more experience or expertise.

But an investigation concluded that the plane had suffered no mechanical defects. The cause of the crash was “pilot error”.

The Model 299 was significantly more complex than previous aircraft. The new plane required the pilot to monitor each of the four engines, and each engine had its own oil-fuel mix. The pilot also had to attend to the retractable landing gear, the wing flaps, trim tabs to maintain stability at different air speeds, and propellers whose pitch needed to be regulated by means of hydraulic controls.

One newspaper wrote that the Boeing model was “too much airplane for one man to fly”. Douglas’ smaller design was therefore judged to be the winner. Boeing nearly went bankrupt.

The army nevertheless purchased a handful of aircraft from Boeing and some engineers remained convinced that the plane could be flown. A group of test pilots got together and deliberated on the problem.

In the words of Atul Gawande,

“What they decided not to do was almost as interesting as what they actually did.”

They did not require Model 299 pilots to undergo longer training. Instead, they came up with an ingenious solution.

They created a pilot’s checklist.

Aeronautics had come quite a way since the days of the Wright brothers. During the dawn of aviation, getting a plane airborne might have been nerve-racking but it was hardly a complex manoeuvre. Using a checklist during take-off would have seemed absurd. But the new model was too complicated to be left to any single person, no matter how expert.

The test pilots kept their checklist simple and concise. It was short enough to fit on an index card, with step-by-step checks for take-off, flight, landing and taxiing. The checklist ensured that the brakes were released, that instruments were set, that doors and windows were closed – elementary stuff. But with the checklist at hand, pilots went on to fly the Model 299 a total of 1.8 million miles without a single accident. The army went on to order almost 13,000 aircraft, which were named the B-17. Because this giant could now be flown without incident, the US army gained a decisive advantage in the Second World War. The pilots’ checklist arguably changed the course of history.

The chances are, if you speak to any financial adviser, they’ll tell you that asset allocation – how you divide up your investible pot among the major asset classes, including debt, equity, property, commodities and alternative investments – is the single most important investment decision you will make. And they’re almost certainly right to do so.

The financial services industry typically cites a study from 1986 by Gary Brinson, Randolph Hood and Gilbert Beebower (BHB) which examined the asset allocation of 91 large pension funds between 1974 and 1983.

BHB replaced those funds’ specific stock, bond and cash selections with comparable market indices. The quarterly returns of the indexed portfolios were found to be higher than the quarterly returns of the more actively managed portfolios. BHB put a figure on it. The correlation between the two series was measured at 96.7%, with a shared variance of 93.6%.

The study’s effective conclusion was that a simple indexed approach worked just as well as using professional fund managers. A secondary conclusion was that a relatively small number of asset classes was sufficient for the purposes of financial planning. Financial advisers have tended to regard the BHB study as proof that asset allocation is much more important than either security selection or market timing combined.

This conclusion is probably broadly correct. But we still believe in active portfolio management.

Why?

Classical economics teaches us that value is subjective. More to the point, the value in investments is also contextual. It is dependent on the wider financial environment.

Consider exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Many financial advisers swear by them. They cite studies like BHB, and point out, quite correctly, that management fees are crucial in the context of longer term returns.

But in keeping portfolio costs down to their lowest levels, these advisers are being penny-wise and pound-foolish. If a given stock market is dangerously expensive by any rational analysis, there’s no point in maintaining exposure to it using a cheap index-tracking instrument.

The rational response is to try and identify a superior (not least by being demonstrably cheaper) market.

By way of a notorious example, we give you the S&P 500 Index.

Source: https://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe

The chart above shows the history of the S&P 500 equity index as assessed by Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted p/e ratio. This is simply a 10 year smoothed average of p/e ratios, which takes out a lot of the noise generated when using a current constant ratio.

Note that at a current Shiller p/e of 29.6, the US broad equity market stands significantly above its long run average of 17. (The market’s lowest ever Shiller p/e was at 4.8 in December 1920 – a great time to be buying stocks. Its highest ever Shiller p/e was at 44.2 in December 1999 – a dreadful time to be buying stocks.)

Note also the little red dot in 1987 which represents the ’87 Crash. Which now looks like a blip.

Note also that the US stock market, on a Shiller basis, has only really been more expensive than today on a handful of occasions: one of them was in 1929, and one of them was in 1999. Draw your own conclusions.

None of which is to say that we’re predicting a Crash. But we are trying to highlight the fact that the broad US stock markets are expensive today. Anybody buying broad market exposure today faces a future of pretty miserable returns, in our opinion. This isn’t an opinion founded on bearishness, just an assessment based on 130 years of market history.

So given a choice between getting cheap index exposure to the US stock market and looking elsewhere for opportunities altogether, we favour looking elsewhere.

But that’s still looking at the investible universe solely through the prism of listed stocks, and there are clearly other ways we can invest our hard-earned cash.

In his book ‘Fail-safe investing’, the late US investment analyst Harry Browne outlines one of the simplest investment philosophies you will ever find. It would go on to find expression in the 1982 launch of the Permanent Portfolio mutual fund (ticker PRPFX US).

Browne’s ‘Fail-safe’ or ‘bullet-proof’ portfolio is a diversified investment portfolio comprising just four asset classes:

Each of these asset classes should, according to Browne, be held to the order of 25% of your overall investments. Each year, simply rebalance each holding back to 25%. The rationale for this approach is as follows.

Stocks offer you a claim on growth in the real economy. During times of prosperity, it’s reasonable to assume that a broad exposure to stocks will deliver decent returns. Browne advocated the use of a basic S&P 500 index fund. Clearly, we have some misgivings about that particular instrument and index, but we acknowledge the basic approach.

Bonds offer you protection in the event of outright deflation. In a more ‘normal’ and low inflationary economic environment, bonds should also deliver respectable returns. But clearly we are not in a normal environment. Interest rates have – until very recently – been falling for over 40 years.

Very few people in any bond dealing room anywhere on the planet have ever seen a sustained bear market for bonds. So it’s worth bearing in mind that in a rising rate environment, or in a credit shock, bonds will do poorly.

Cash offers you a hedge of sorts in the event of “tight money” or recession. In outright deflation it makes sense to hold cash, provided it’s with a banking institution of sufficient creditworthiness. Don’t forget that the moment you park your money in a bank, legally it is no longer your money, but the bank’s. You become an unsecured creditor of the bank.

Gold should offer you a degree of protection in an environment of high inflation, or financial systemic distress.

It has also existed as a form of sound money for thousands of years, and we see huge merit in holding gold – in the right form – in the context of a global debt crisis and international currency war that shows no signs of being resolved.

Dylan Grice, formerly a strategist at French investment bank SocGen, has written a nice companion piece to Browne’s ‘Failsafe investing’. It was Dylan’s final strategy piece on leaving SocGen, published in November 2012 and titled ‘Cockroaches for the long run!’

Dylan’s thesis goes as follows.

The humble cockroach gets something of a bad press, but it is undoubtedly a survivor.

The oldest cockroach fossil is 350 million years old. Human beings, by way of contrast, have only been around for roughly 50,000 years. And cockroaches survived the third, fourth and fifth global mass extinctions (the last being the Cretaceous period event that did for the dinosaurs).

Cockroaches can go without air for 45 minutes, survive submerged under water for half an hour, and can survive freezing temperatures. They can even withstand 15 times more radiation than humans – so they stand a good chance of surviving a nuclear war.

But they operate according to one of the simplest algorithms in nature. Richard Bookstaber describes it as:

“singularly simple and seemingly suboptimal: it moves in the opposite direction of gusts of wind that might signal an approaching predator.”

That’s it. Simple – but spectacularly robust.

Dylan goes on to ask: if you were going to try and replicate the robustness of a cockroach within an investment portfolio, what might that portfolio look like?

His first stab at creating the robust portfolio is the “cockroach wannabe”: a portfolio consisting of 50% bonds, 50% equities. The problem with the “cockroach wannabe” is that it isn’t really as robust as it sounds. Consider the performance of the “cockroach wannabe” during the 1970s – a decade that saw horrific drawdowns in both bonds and stocks..

As Dylan’s chart above makes clear, although the “cockroach wannabe” fared somewhat better than stocks (in blue in the chart above) – which saw peak to trough losses of over 50% during the mid-70s – it was hardly as resistant to market plunges as its namesake. The selloff in bonds (shown in grey) was almost as gruelling; and the “cockroach wannabe”, shown in black, fared almost as badly as debt investments, and in some instances worse.

So Dylan’s conclusion ends up being very similar to that of Harry Browne.

Dylan’s “cockroach portfolio” would be inflation resistant, deflation resistant, credit inflation resistant, credit deflation resistant… despite having no view on which scenario was more likely at any given point in time.

So the cockroach doesn’t make any outright bets. It puts half of its money into real assets, and the other half into nominal ones. It then divides its nominal and real allocations further, into productive and unproductive assets. It puts 25% of its portfolio into stocks, 25% into gold, 25% into government bonds, and it keeps 25% in the form of cash.

So how does the “true cockroach” portfolio fare versus the wannabe? The chart below reveals all.

The “true cockroach” portfolio – with exactly the same asset mix as Harry Browne’s original Permanent Portfolio – offers some very real protection against the vagaries of an unknown future. Compared with the drawdowns experienced by either stock markets or bonds, the “true cockroach” emerges from market crises more or less completely unscathed.

And over the course of Dylan’s timeline (1971 to 2011) the returns weren’t bad either: 5% real (after-inflation) returns since 1971, compared with 5.5% real returns for equities, and 4% real returns from government bonds.

So if you’re motivated primarily by risk avoidance and capital preservation, there are certainly worse strategies to consider than the Permanent Portfolio / “Cockroach Portfolio” approach.

If we were to distil the Permanent Portfolio philosophy into a checklist, it would look something like this:

The reason we say this is that the Yale Endowment, under the supervision of David Swensen, one of the world’s most well respected institutional investors, managed to lose something like 25% of its value between 2007 and 2008. One of the reasons it lost so much money is that it did not have any exposure to the one asset class that would, back then, have preserved its capital.

In fact, the Yale Endowment was outright short US Treasury debt during the period in question.

If they had had meaningful exposure to US Treasuries, they would have recorded decent gains from those holdings. The fail-safe portfolio is blind to the vagaries of the herd. We simply do not know what the future holds.

Given that US market valuations currently look stretched, you may well want to consider international markets as well. We see especial value today in commodities stocks, ideally those unencumbered by high levels of debt.

That caters to the asset allocation process. If we look more specifically at just the equity portion of a portfolio, our checklist would look something like this:

iii) The shares are trading at an attractive discount to any objective assessment of their inherent value or, at the very least, are not trading at an uncomfortably high multiple in terms of price / book or price / earnings.

All things equal, a price / book of less than 1.5x is preferred, as is a price / earnings ratio of 15x or less. Having little or no debt is also preferred.

“I could improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only twenty slots in it so that you had twenty punches – representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime. And once you’d punched through the card, you couldn’t make any more investments at all. Under those rules, you’d really think carefully about what you did, and you’d be forced to load up on what you’d really thought about. So you’d do so much better.”

—

We began this week’s letter with a downed plane. Sick people, as Atul Gawande points out in his book ‘The checklist manifesto’, are extraordinarily more various than airplanes. He cites a study of 41,000 trauma patients in the state of Pennsylvania. Those patients had 1,224 different injury-related diagnoses, in 32,261 unique combinations.

“That’s like having 32,261 kinds of airplane to land.”

The solution? Simplify. And, perhaps, incorporate some form of checklist into your own investment process. What works in an airplane or in a hospital stands a good chance of working in your own portfolio. Look at it another way: how many mistakes can you survive ?

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you, too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio -with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and specialist managed funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price