“The historic shift from Keynesian economics occurred in 1976, when Labour’s chancellor Denis Healey imposed public spending cuts after being forced to seek a loan from the International Monetary Fund to avert what he feared would be national bankruptcy. When Thatcher entered Downing Street, three years later, she did so not as an exponent of any economic theory, but rather – as one of her close advisers put it to me at the time – as “the reality principle in skirts”..

“The global financial markets on which Britain’s solvency depends are starting to suspect that Rachel Reeves’ Budget on 30 October will not add up. War in the Middle East could trigger an oil shock that would rekindle inflation and derail all her fiscal formulae. National borders are being reasserted across Europe. The Polish prime minister, Donald Tusk, an avowed liberal, has announced a “temporary” ban on asylum seekers entering the country, citing the undeniable fact that Russia and Belarus are weaponising migrants in their hybrid warfare against the West. If Donald Trump wins the American presidential election and imposes high tariffs on Chinese imports as he has threatened, Britain will find itself in the middle of a devastating trade war. Whatever the outcome, the US will be plunged into bitterness and introversion – a moment of opportunity for Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping. The international liberal order in which Keir Starmer and David Lammy insist Britain belongs is coming to an end. Labour confronts an enigma of arrival: the world it expected to join when it came to power does not exist..

“Unsustainably high inflows of migrants and stretched public services are concerns that unite a British majority. They will not be assuaged by a tweaked version of Starmer’s moralising, invasive and incompetent state.

“Nor can the issues that concern voters be magically resolved simply by changing the law, as some on the right seem to believe. Setting a statutory cap on immigration, for example, is a mirror-image of left-liberal legalism, which – like Ed Miliband’s net zero targets – will prove unenforceable. Seriously grappling with Britain’s problems involves confronting their roots in a swollen apparatus of government, ideologically captured institutions and civilisational decline.”

Get your Free

financial review

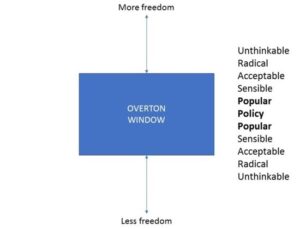

In the aftermath of Starmer’s first Budget and an even-by-historical-standards wildly divisive and polarising US Presidential election, we can expect to hear a lot more about the Overton window over the coming months. Named after public policy advocate Joseph Overton, the Overton window describes the range of ideas that at any one time will be tolerated by the public.

The political commentator Joshua Treviño then supplemented the concept with various degrees of acceptance, in the direction of either libertarianism or authoritarianism, such that the “full” Overton window is shown below.

The Overton window, incorporating Treviño’s degrees of acceptance

After Overton’s death, his colleague Joseph Lehman developed the idea and gave it its name. As he went on to explain, politics is not about moving the window, but operating within it as it flexes and bends:

“The most common misconception is that lawmakers themselves are in the business of shifting the Overton window. That is absolutely false. Lawmakers are actually in the business of detecting where the window is, and then moving to be in accordance with it.”

This, to our mind, recalls the observation made by the German physicist Max Planck, in his case about the evolution of scientific progress, namely that science advances one funeral at a time. In other words, such cultural development is not orderly but messily organic; people are resistant to new ideas, and it is only when the stubborn resistance to novel ideas that might also be more accurate about the nature of the world dies out that we make progress into the future. (We are not suggesting here that the changing nature of the Overton Window reflects a more truthful, objectively morally or culturally better or worse world. The Overton Window simply is what it is.)

In any event, the combination of the global financial crisis (GFC), Brexit, Donald Trump, the Covid crisis and a new geopolitical order make for an Overton window that is changing more dramatically in scope, and faster, perhaps, than ever before. In some respects (the Biden administration and now the Starmer one) the Overton Window has already shifted markedly to the left.

We imagine that psychologists up and down the land are already busily writing books about how and why the country collectively lost its mind in the aftermath of the 2016 referendum. We believe you can make a plausible case that much of the current evolution of the shape of the Overton window can be traced back to the GFC itself.

The Western economic model, if you can call it that, was tested – and found wanting. Instead of advocating or permitting some form of gigantic economic reset that would have seen bad banks fail and unpayable debts voided, the Western political class instead chose a route incorporating no hard decisions, gruesome support for failed businesses, government intervention on a scale never before seen in peacetime, and the perpetuation of a warped form of capitalism that can be better described as crapitalism or crony capitalism.

Times change.

Seen through the prism of financial opportunity (or lack thereof – see our recent commentary ‘How to survive interesting times’), the disenchantment of the younger generation with the current political and economic system suddenly seems a lot more understandable. The Overton window flexes again.

‘MoneyWeek’ held a Wealth Summit a while back, at which the panellists James Ferguson, Gillian Tett of the ‘Financial Times’ and then MEP and now member of the House of Lords Daniel Hannan discussed the state of the world. They were followed by one of our favourite analysts, the financial historian Russell Napier (here passim).

Somewhat ominously, the panellists were in broad agreement that the global debt predicament, and its attendant threat of deflation (see Japan for more on this topic), is now so severe that the rollout of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) now looks to be more or less inevitable. Now that is a shift in the Overton window.

If you’re unfamiliar with MMT, here’s the short version.

The essence of MMT is that governments within a fiat currency system should create as much money as they need to fund whichever economic programmes they desire because they can never go bankrupt, except by conscious choice.

If this sounds like dangerous nonsense, you have the same respect for MMT that we do.

And the same respect that economist Paul Krugman does. In a 2011 op-ed for ‘The New York Times’, he wrote:

“The point is that there are limits to the amount of real resources that you can extract through seigniorage [the profit government makes from issuing its own currency]. When people expect inflation, they become reluctant to hold cash, which drive prices up and means that the government has to print more money to extract a given amount of real resources, which means higher inflation, etc… Do the math, and it becomes clear that any attempt to extract too much from seigniorage — more than a few percent of GDP, probably — leads to an infinite upward spiral in inflation. In effect, the currency is destroyed. This would not happen, even with the same deficit, if the government can still sell bonds.

“The point is that under normal, non-liquidity-trap conditions, the direct effects of the deficit on aggregate demand are by no means the whole story; it matters whether the government can issue bonds or has to rely on the printing press. And while it may literally be true that a government with its own currency can’t go bankrupt, it can destroy that currency if it loses fiscal credibility.”

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it (George Santayana). It would seem that advocates of MMT either cannot or do not remember the terrible impact of the Weimar hyperinflation, not to say other episodes of complete monetary insanity.

While we are no great advocates of echo chambers, we were heartened to hear both James Ferguson and Russell Napier reiterate the merits of owning gold in the world that may yet be to come (if it is not indeed already here). Napier also warned of the perils of financial repression. That will be another likely characteristic of Starmer’s government.

So those are our primary concerns. Is there any way to try and protect ourselves and our portfolios from the worst case scenario ?

As a matter of fact, there is.

Longstanding subscribers will know that our single favourite form of “absolute return” vehicle is the systematic trend-following fund. The “systematic” part involves using a mathematical system, as opposed to human discretion. The “trend-following” part means that such funds are driven primarily by price momentum, and not, again, by any form of human discretion.

We use systematic trend-following funds in our wealth management business for three specific reasons:

1) Their long-term returns have been impressive – on a par with equity market returns, but with significantly less risk during market downturns.

2) They tend to offer very little or no correlation to traditional (i.e. stock and bond) markets, so are therefore good diversifiers within a balanced portfolio.

3) They tend to offer superior risk management and portfolio protection versus traditional assets (and asset managers), especially during periods of systemic crisis.

The main ‘problem’ with systematic trend-following funds is that, as most of them are constituted as hedge funds, they have high minimum investment thresholds and cannot be marketed to individual investors for regulatory reasons. They can only be marketed to “accredited investors”. Because they are often volatile in the short run, many institutional fund managers are also scared of using them. (Those managers should take a look at the volatility of the stock market once in a while.)

Nevertheless, as either an alternative to traditional asset exposure or as a complement to it, we think systematic trend-following funds have real merit.

Another of our preferred investments speaks for itself by way of recent price action. As George Bernard Shaw put it (emphasis ours):

“You have to choose between trusting to the natural stability of gold and the natural stability of the honesty and intelligence of the members of the Government. And, with due respect for these gentlemen, I advise you, as long as the Capitalist system lasts, to vote for gold.”

The Overton window is not the only window we would like to discuss this week. We would also like to remind readers of Frédéric Bastiat’s ‘Broken Window Fallacy’. The following is an extract from our 2016 book, ‘Investing Through the Looking Glass’:

“Perhaps the most famous fable in the history of economics – itself a compendium of increasingly tall tales – is Frédéric Bastiat’s 1850 story of the broken window.

“The son of a Parisian shopkeeper accidentally shatters a pane of glass. A crowd gathers at the scene. Admittedly, the shopkeeper is out of pocket by the cost of a window. But the glazier just summoned will reap the benefit. Where would poor glaziers be in a world without broken windows? Imagine all the good uses to which the glazier can put his new-found windfall from repairing the damage. Think what he could buy. All that new money circulating through the economy. Perhaps we might all be better off if more windows got broken on a regular basis ?

“Stop there!” cries Bastiat, addressing the crowd directly. “Your theory is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen.” Hence the title of Bastiat’s essay: ‘That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen’.

“The six francs paid to the glazier for effecting his repairs are what is seen. The crowd can speculate to its heart’s content to what luxurious end those francs might be expended. But what is not seen is what the shopkeeper might have done with those six francs if he had not had to pay them to the glazier in the first instance. He would, perhaps, have bought some new shoes, or a book for his library. “To break, to spoil, to waste, is not to encourage national labour; or, more briefly, destruction is not profit.”

“In the modern economy, government plays a significant role. While it doesn’t create wealth – entrepreneurial activity does that – government redistributes it. That process of capital redistribution involves winners and losers. Government projects may seem to create work for some, but there is also someone who must pay for them, and that someone is normally the taxpayer. And if the capital is raised from the bond market, it doesn’t come directly from today’s taxpayer – it is extracted from tomorrow’s. Such projects may also divert spending from a more deserving group. Some government spending might even involve the outright destruction of wealth. There are, after all, only three ways in which money can be spent. You can spend your own money on yourself. You can spend your own money on other people. Or you can spend other people’s money on other people. The last is the spending prerogative of government.

“As the world economy gets ever more financialised, and as ever more capital starts flowing in ways that are less than wholly transparent, Bastiat’s metaphor only becomes more powerful over time. In the words of Henry Hazlitt: “the broken window fallacy, under a hundred disguises, is the most persistent in the history of economics.”

Of necessity, this commentary was written before both the inaugural new Labour Budget and the US Presidential elections. We suspect the ramifications of both will endure for years. We reiterate our commitment to capital preservation and to economically productive real assets (including the likes of gold and silver) – as opposed to politicians’ increasingly empty promises and interventions.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio – with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

…………

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and also in systematic trend-following funds.

“The historic shift from Keynesian economics occurred in 1976, when Labour’s chancellor Denis Healey imposed public spending cuts after being forced to seek a loan from the International Monetary Fund to avert what he feared would be national bankruptcy. When Thatcher entered Downing Street, three years later, she did so not as an exponent of any economic theory, but rather – as one of her close advisers put it to me at the time – as “the reality principle in skirts”..

“The global financial markets on which Britain’s solvency depends are starting to suspect that Rachel Reeves’ Budget on 30 October will not add up. War in the Middle East could trigger an oil shock that would rekindle inflation and derail all her fiscal formulae. National borders are being reasserted across Europe. The Polish prime minister, Donald Tusk, an avowed liberal, has announced a “temporary” ban on asylum seekers entering the country, citing the undeniable fact that Russia and Belarus are weaponising migrants in their hybrid warfare against the West. If Donald Trump wins the American presidential election and imposes high tariffs on Chinese imports as he has threatened, Britain will find itself in the middle of a devastating trade war. Whatever the outcome, the US will be plunged into bitterness and introversion – a moment of opportunity for Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping. The international liberal order in which Keir Starmer and David Lammy insist Britain belongs is coming to an end. Labour confronts an enigma of arrival: the world it expected to join when it came to power does not exist..

“Unsustainably high inflows of migrants and stretched public services are concerns that unite a British majority. They will not be assuaged by a tweaked version of Starmer’s moralising, invasive and incompetent state.

“Nor can the issues that concern voters be magically resolved simply by changing the law, as some on the right seem to believe. Setting a statutory cap on immigration, for example, is a mirror-image of left-liberal legalism, which – like Ed Miliband’s net zero targets – will prove unenforceable. Seriously grappling with Britain’s problems involves confronting their roots in a swollen apparatus of government, ideologically captured institutions and civilisational decline.”

Get your Free

financial review

In the aftermath of Starmer’s first Budget and an even-by-historical-standards wildly divisive and polarising US Presidential election, we can expect to hear a lot more about the Overton window over the coming months. Named after public policy advocate Joseph Overton, the Overton window describes the range of ideas that at any one time will be tolerated by the public.

The political commentator Joshua Treviño then supplemented the concept with various degrees of acceptance, in the direction of either libertarianism or authoritarianism, such that the “full” Overton window is shown below.

The Overton window, incorporating Treviño’s degrees of acceptance

After Overton’s death, his colleague Joseph Lehman developed the idea and gave it its name. As he went on to explain, politics is not about moving the window, but operating within it as it flexes and bends:

“The most common misconception is that lawmakers themselves are in the business of shifting the Overton window. That is absolutely false. Lawmakers are actually in the business of detecting where the window is, and then moving to be in accordance with it.”

This, to our mind, recalls the observation made by the German physicist Max Planck, in his case about the evolution of scientific progress, namely that science advances one funeral at a time. In other words, such cultural development is not orderly but messily organic; people are resistant to new ideas, and it is only when the stubborn resistance to novel ideas that might also be more accurate about the nature of the world dies out that we make progress into the future. (We are not suggesting here that the changing nature of the Overton Window reflects a more truthful, objectively morally or culturally better or worse world. The Overton Window simply is what it is.)

In any event, the combination of the global financial crisis (GFC), Brexit, Donald Trump, the Covid crisis and a new geopolitical order make for an Overton window that is changing more dramatically in scope, and faster, perhaps, than ever before. In some respects (the Biden administration and now the Starmer one) the Overton Window has already shifted markedly to the left.

We imagine that psychologists up and down the land are already busily writing books about how and why the country collectively lost its mind in the aftermath of the 2016 referendum. We believe you can make a plausible case that much of the current evolution of the shape of the Overton window can be traced back to the GFC itself.

The Western economic model, if you can call it that, was tested – and found wanting. Instead of advocating or permitting some form of gigantic economic reset that would have seen bad banks fail and unpayable debts voided, the Western political class instead chose a route incorporating no hard decisions, gruesome support for failed businesses, government intervention on a scale never before seen in peacetime, and the perpetuation of a warped form of capitalism that can be better described as crapitalism or crony capitalism.

Times change.

Seen through the prism of financial opportunity (or lack thereof – see our recent commentary ‘How to survive interesting times’), the disenchantment of the younger generation with the current political and economic system suddenly seems a lot more understandable. The Overton window flexes again.

‘MoneyWeek’ held a Wealth Summit a while back, at which the panellists James Ferguson, Gillian Tett of the ‘Financial Times’ and then MEP and now member of the House of Lords Daniel Hannan discussed the state of the world. They were followed by one of our favourite analysts, the financial historian Russell Napier (here passim).

Somewhat ominously, the panellists were in broad agreement that the global debt predicament, and its attendant threat of deflation (see Japan for more on this topic), is now so severe that the rollout of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) now looks to be more or less inevitable. Now that is a shift in the Overton window.

If you’re unfamiliar with MMT, here’s the short version.

The essence of MMT is that governments within a fiat currency system should create as much money as they need to fund whichever economic programmes they desire because they can never go bankrupt, except by conscious choice.

If this sounds like dangerous nonsense, you have the same respect for MMT that we do.

And the same respect that economist Paul Krugman does. In a 2011 op-ed for ‘The New York Times’, he wrote:

“The point is that there are limits to the amount of real resources that you can extract through seigniorage [the profit government makes from issuing its own currency]. When people expect inflation, they become reluctant to hold cash, which drive prices up and means that the government has to print more money to extract a given amount of real resources, which means higher inflation, etc… Do the math, and it becomes clear that any attempt to extract too much from seigniorage — more than a few percent of GDP, probably — leads to an infinite upward spiral in inflation. In effect, the currency is destroyed. This would not happen, even with the same deficit, if the government can still sell bonds.

“The point is that under normal, non-liquidity-trap conditions, the direct effects of the deficit on aggregate demand are by no means the whole story; it matters whether the government can issue bonds or has to rely on the printing press. And while it may literally be true that a government with its own currency can’t go bankrupt, it can destroy that currency if it loses fiscal credibility.”

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it (George Santayana). It would seem that advocates of MMT either cannot or do not remember the terrible impact of the Weimar hyperinflation, not to say other episodes of complete monetary insanity.

While we are no great advocates of echo chambers, we were heartened to hear both James Ferguson and Russell Napier reiterate the merits of owning gold in the world that may yet be to come (if it is not indeed already here). Napier also warned of the perils of financial repression. That will be another likely characteristic of Starmer’s government.

So those are our primary concerns. Is there any way to try and protect ourselves and our portfolios from the worst case scenario ?

As a matter of fact, there is.

Longstanding subscribers will know that our single favourite form of “absolute return” vehicle is the systematic trend-following fund. The “systematic” part involves using a mathematical system, as opposed to human discretion. The “trend-following” part means that such funds are driven primarily by price momentum, and not, again, by any form of human discretion.

We use systematic trend-following funds in our wealth management business for three specific reasons:

1) Their long-term returns have been impressive – on a par with equity market returns, but with significantly less risk during market downturns.

2) They tend to offer very little or no correlation to traditional (i.e. stock and bond) markets, so are therefore good diversifiers within a balanced portfolio.

3) They tend to offer superior risk management and portfolio protection versus traditional assets (and asset managers), especially during periods of systemic crisis.

The main ‘problem’ with systematic trend-following funds is that, as most of them are constituted as hedge funds, they have high minimum investment thresholds and cannot be marketed to individual investors for regulatory reasons. They can only be marketed to “accredited investors”. Because they are often volatile in the short run, many institutional fund managers are also scared of using them. (Those managers should take a look at the volatility of the stock market once in a while.)

Nevertheless, as either an alternative to traditional asset exposure or as a complement to it, we think systematic trend-following funds have real merit.

Another of our preferred investments speaks for itself by way of recent price action. As George Bernard Shaw put it (emphasis ours):

“You have to choose between trusting to the natural stability of gold and the natural stability of the honesty and intelligence of the members of the Government. And, with due respect for these gentlemen, I advise you, as long as the Capitalist system lasts, to vote for gold.”

The Overton window is not the only window we would like to discuss this week. We would also like to remind readers of Frédéric Bastiat’s ‘Broken Window Fallacy’. The following is an extract from our 2016 book, ‘Investing Through the Looking Glass’:

“Perhaps the most famous fable in the history of economics – itself a compendium of increasingly tall tales – is Frédéric Bastiat’s 1850 story of the broken window.

“The son of a Parisian shopkeeper accidentally shatters a pane of glass. A crowd gathers at the scene. Admittedly, the shopkeeper is out of pocket by the cost of a window. But the glazier just summoned will reap the benefit. Where would poor glaziers be in a world without broken windows? Imagine all the good uses to which the glazier can put his new-found windfall from repairing the damage. Think what he could buy. All that new money circulating through the economy. Perhaps we might all be better off if more windows got broken on a regular basis ?

“Stop there!” cries Bastiat, addressing the crowd directly. “Your theory is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen.” Hence the title of Bastiat’s essay: ‘That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen’.

“The six francs paid to the glazier for effecting his repairs are what is seen. The crowd can speculate to its heart’s content to what luxurious end those francs might be expended. But what is not seen is what the shopkeeper might have done with those six francs if he had not had to pay them to the glazier in the first instance. He would, perhaps, have bought some new shoes, or a book for his library. “To break, to spoil, to waste, is not to encourage national labour; or, more briefly, destruction is not profit.”

“In the modern economy, government plays a significant role. While it doesn’t create wealth – entrepreneurial activity does that – government redistributes it. That process of capital redistribution involves winners and losers. Government projects may seem to create work for some, but there is also someone who must pay for them, and that someone is normally the taxpayer. And if the capital is raised from the bond market, it doesn’t come directly from today’s taxpayer – it is extracted from tomorrow’s. Such projects may also divert spending from a more deserving group. Some government spending might even involve the outright destruction of wealth. There are, after all, only three ways in which money can be spent. You can spend your own money on yourself. You can spend your own money on other people. Or you can spend other people’s money on other people. The last is the spending prerogative of government.

“As the world economy gets ever more financialised, and as ever more capital starts flowing in ways that are less than wholly transparent, Bastiat’s metaphor only becomes more powerful over time. In the words of Henry Hazlitt: “the broken window fallacy, under a hundred disguises, is the most persistent in the history of economics.”

Of necessity, this commentary was written before both the inaugural new Labour Budget and the US Presidential elections. We suspect the ramifications of both will endure for years. We reiterate our commitment to capital preservation and to economically productive real assets (including the likes of gold and silver) – as opposed to politicians’ increasingly empty promises and interventions.

………….

As you may know, we also manage bespoke investment portfolios for private clients internationally. We would be delighted to help you too. Because of the current heightened market volatility we are offering a completely free financial review, with no strings attached, to see if our value-oriented approach might benefit your portfolio – with no obligation at all:

Get your Free

financial review

…………

Tim Price is co-manager of the VT Price Value Portfolio and author of ‘Investing through the Looking Glass: a rational guide to irrational financial markets’. You can access a full archive of these weekly investment commentaries here. You can listen to our regular ‘State of the Markets’ podcasts, with Paul Rodriguez of ThinkTrading.com, here. Email us: info@pricevaluepartners.com.

Price Value Partners manage investment portfolios for private clients. We also manage the VT Price Value Portfolio, an unconstrained global fund investing in Benjamin Graham-style value stocks and also in systematic trend-following funds.

Take a closer look

Take a look at the data of our investments and see what makes us different.

LOOK CLOSERSubscribe

Sign up for the latest news on investments and market insights.

KEEP IN TOUCHContact us

In order to find out more about PVP please get in touch with our team.

CONTACT USTim Price